Janardan Ghosh’s Kayantar – Towards the need for Transformation

KAYANTAR- A film co-directed by Rajdeep Paul & Sarmistha Maity

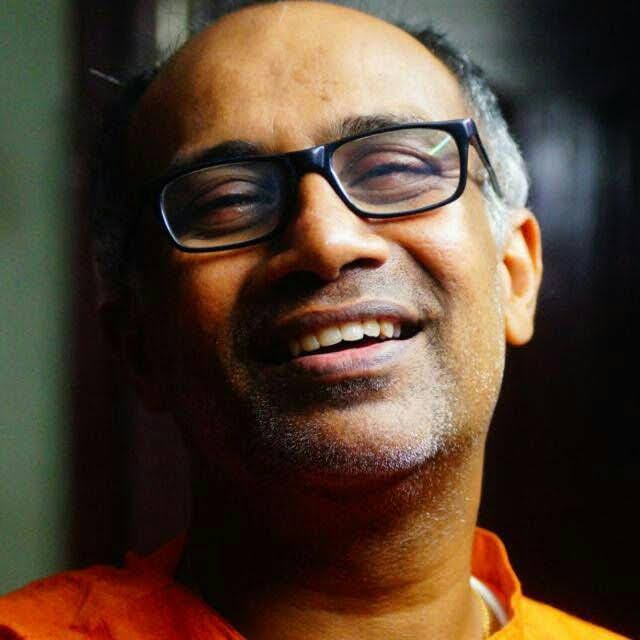

The lead actor in the film, Dr Janardan Ghosh, is really versatile and multi talented. He is a performing artist, academic, theatre director, film actor, playwright, performance coach and storyteller (Katha ‘Koli, a new art of storytelling) whose practice includes the use of traditional theories, contemporary performance vocabulary, and interactive media. His research-based work engages the indigenous practice methods in urban spaces exploring the perspectives of historicity, spiritual consciousness, intertextual dialogue, and body-space dynamics of myths, tales and gossips.

Kayantar- is a poignant tale of religious discrimination that leads to repenting circumstances for those that are forced to quietly endure and hence implicitly exploited to endorse conformity to the extent of losing their identities and eventually their lives. Moreover, it is a tale that has a sub-plot dealing with the pathos of the Bahurupi artists who beg in front of the people for their survival; their art not being recognized as a respectable profession but being condemned as a demeaning activity, pursued by those that are financially underprivileged and become nomadic thus imploring in front of the people for alms in order to make both ends meet.

The film is heart-wrenching as we see how the Bahurupi Muslim artist (played by Dr. Janardan Ghosh) dressed as the Hindu Goddess Kali appears in front of his two children; only to consecutively become crippled and hence forcefully passing on his legacy to his son who dislikes pursuing his father’s profession. The son has a point. He being a Muslim roaming around in the apparel of a Hindu Goddess is disparaged by the religious stalwarts of his community, is mocked at by the children of the village and is boycotted by many conservatives as ‘Bhikhari’ – a pauper. These facts reiterated in an overtly painful and innately stark undertone are enough evidences to make the pangs of the young man believable and evocative of the viewers’ empathy for him.

That the innocent youth who has not acquired this profession by his own choice and it has been rather forced on him comes as a harsh and undeniable truth that grills our thinking capacities to the extent of questioning all our modern theories of global indivisibilities of culture and religion. When the young lad takes an anomalous decision to choose a girl of the rival community and loses his life because of being engulfed in the holocaust of communal riots that take place in his village, our conscience gets stirred and we as viewers of the film are compelled to revise our notions of living in an industrialized, progressive world. We are made to rethink whether the circumferences of culture, creed, race and religion only exist on national borders or are they still prevalent somewhere within our psyches and we are only ignoring these under the pretext of being the civilized community.

Within the framework of a story that so effectively becomes pertinent with the theme of universal relevance as we still find the world divided into castes and communities and people identifying themselves through their religions, there is a very intriguing story of Asia, the young girl who wishes to adorn herself as Kali and pursue her Bahurupi father’s profession with confidence and dignity. The tale comes as an pleasant surprise when Asia is founded engaging herself in painting her body coal black and rejoicing to see herself in the gruesome look. It seems a woman’s reclusive identification of the other dimension of the divine feminine that exists within her apparent demure image of a meek girl.

That Kali chooses Asia’s body to be her abode is also a fact that demands our prudent understanding of the fact that religious differences prevail only on the superficial level as the Bahurupi keeps singing “Apanar Apni fana hole shei bhed jana jai”- Means that realization comes only when the distinction between mine and yours gets erased. Such an indubitable truth of the oneness of divinity is fondly repeated as a backdrop of the entire film makes the theme of the movie apparent- It is not by dividing but it is by uniting that humanity can realize in the oneness of this universe wherein every entity is the fragment of that supreme energy that we call God. The philosophical context in the film does not let the film lose its ties with an integral theme of gender discrimination.

Asia takes the permission of her father to dress up as Kali and pursue her profession as a Bahurupi. Nonetheless, the Bahurupi, her father, gets annoyed with her and says that he cannot allow his daughter to wander on the roads as a prostitute. Why the man who has earned a living with the same profession disallows his daughter to follow his footsteps? The film gives us a jolt when we hear these words of the Bahurupi. If it were such a demeaning profession, why on earth did he adopt it? Was he also forced by his family to adopt it and with great reluctance he went on from door to door dressed up as Kali and asked for money from the people? The film does not answer these questions but raising these queries in our minds the film acts as a thunderbolt when we see a Muslim girl adopting her father’s profession ultimately when her brother dies in the communal riots and she has to earn a living for her home ultimately as her father is crippled and is unable to do anything to make a living. Though she finally opts to become Kali, the intimidating figure of the bloodthirsty goddess who is so venomous becomes the most pensive image of pathos; she has to become Kali only to support her family and this time her father is helpless and cannot stop her even if he wants to. She walks on the railway track fearlessly continuing her journey on the route that has her brother’s remnants that remind us of the gruesome ending that the young boy faced due to his unfortunate choice.

Diluting the conformist image of Kali as a fearsome goddess, Kayantar presents another facet of hers as a sad feminine figure who wanders helplessly for recognition. When she walks on the road men do not fear her ghastly appearance. They in fact dare to tease her which undermines her ferocity only to expose the truth that a woman’s frightening exterior cannot dismantle the atrocities meted out to her in a man’s world. She may be regarded as an epitome of Kali and the goddess may have chosen her to manifest her form but the fact remains that she is an ordinary woman confined within domestic sphere that does not allow her to operate according to her will and discretion. Her life is what a man wants it to be. She may dress up as Kali but she will never be regarded equal to the formidable goddess of the temples and the cemeteries. She will remain as an ordinary woman. When the Bahurupi tries to disclose the truth in front of her thus refusing her to wander on the roads as Kali, it is this harsh reality that he tries to explain to her which remains unadulterated truth pertinent to all times.

That a woman is exploited under the pretext of granting her equal rights and overt sexual violence and tacit manipulation are indeed a part of this so called man’s world even today are not hidden realities but are undeniable truths. Kayantar shows that if Kali wanders as an ordinary powerless woman Asia, she will be shamed. The film aptly demystifies the wrathful image of Kali and extracts the ordinary femininity in her that seeks recognition till date.

When the goddess Kali accidently stepped on Kala- Lord Shiva as per the mythical account, she was unhappy and wailed for the fact that she had made a grave mistake of putting her feet on her husband’s chest; a sinful conduct for a woman as per the conventional theories of Hinduism. It is not Kali’s pathos that is underpinned in the temples when we worship her as the mother goddess. It is her ire that is being continually recognized and the red tongue that lolled accidently out of her mouth due to her unconscious act of putting her feet on Shiva’s chest is ironically regarded as a mark of her fearful image. Kayantar shows the other aspect of this horrific Kali and that is – Kali as the one that resides in the domicile of an artist who earns his morsel of food by emoting her from door to door. When the Kayantar takes place and the Bahurupi allows her to possess him, the possession is just on the level of the exterior. There is no internal possession because the artist cannot afford it. He is supposed to be submissive and not exert his redoubtable image in front of others. He is a beggar.

The film talks about the pathos of the village artists that pursue their profession only as a means of earning the basic necessities in life. With the advent of complex technologies in the realm of entertainment, these artists are deprived of their due recognition. Kayantar – the transformation is of the body and not the soul but this is what the film seems to have intended. The ardour of transforming one’s soul is explained through the restraint that the Bahurupi imposes on himself and his son who both dress up as Kali only because they have to earn money to win their bread and butter. There is no philosophical enlightenment in the process of transforming themselves. It stays at the superficial level even after the Bahurupi keeps singing the song ‘Apnar Apni fana hole shei bhed jana jai- which talks about the need to escalate beyond the boundaries of time and space to realize divinity.

The song remains merely a song and the spiritual message ingrained in it is only a matter of speculation. In the end, the Muslim girl Asia adopting Kali’s image does undermine religious discrimination but it does not become prominent because; the extremely painful state of a girl who takes up a vocation on account of a drastic change that occurs in her life of losing her own brother is a telling tale that completely dilutes the fury in the image she adopts and brings out the agony of an ordinary woman incarcerated in the prison of conformity that she is unable to challenge or disown.

All in all, Kayantar is a film that stimulates us to understand religion beyond the confines of the right and the wrong and urges us to revise our cliché associations of Gods and Goddesses as intimidating figures of the temples who possess their disciples that invoke them in the temple rituals. It certainly is an eye-opener to the fact that the transformation of our soul is needed but is often occluded by our senses governed by selfish motives that thwart the spiritual awakening which engenders the realization of truth.

For comments on the article please write in the box given below: