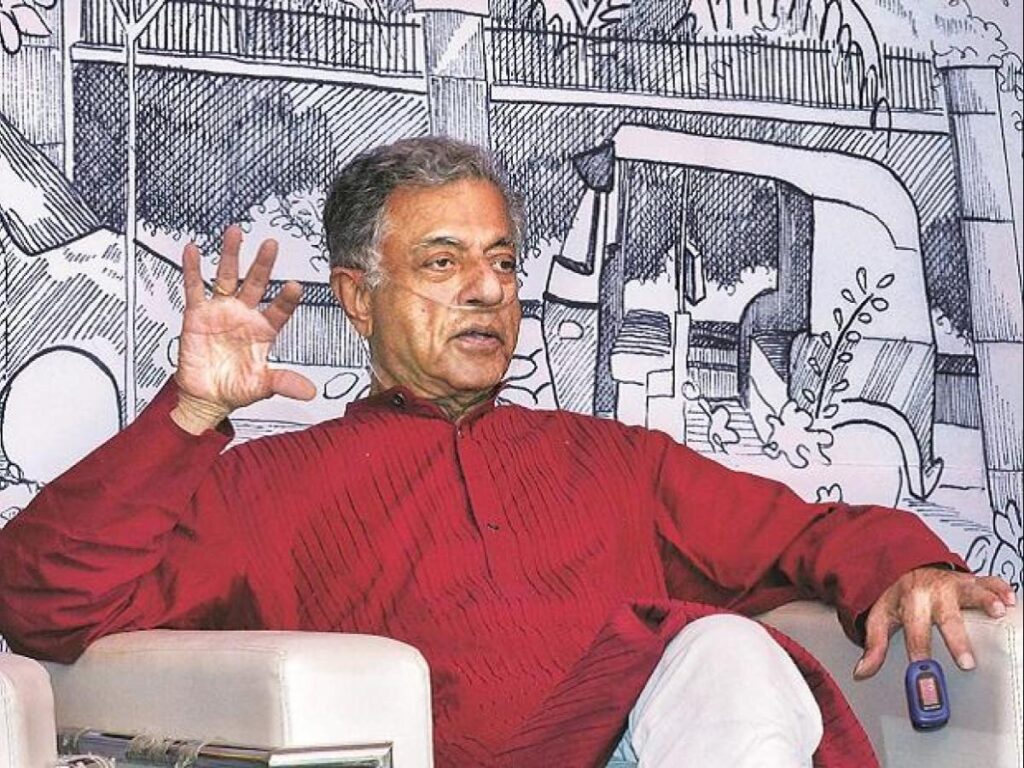

Girish Karnad – Remembering A Multifaceted Mesmerising Actor, Writer, Director

Girish Karnad’s demise on 10 June 2019 marked the end of an era in Indian Theatre. He was 81 and for the last two years suffering from a respiratory ailment that forced him to carry a portable oxygen cylinder and a thin tube across his nostrils; this however, did not prevent him from attending Gauri Lankesh’s first death anniversary and solidarity meet where the friends and admirers of the courageous journalist murdered by goons of the Hindu Right Wing, had gathered in the name of sanity and humanity.

Karnad’s passing was headline news and even those who did not know that he was one of creators of modern Indian theatre and its most intellectual contributor were aware of his highly influential presence because of his activities in other fields namely the cinema as an actor and director, and on Television, where he is remembered as Swami(Nathan)’s father in the hugely popular Television series Malgudi Days, directed by Shankar Nag, based on R.K. Narayan’s evocative short novel Swami and his Friends set in the fictional small town of Malgudi in the Madras Presidency in British India.

All said and done, his genuine versatility taken into account, he will still be remembered as a playwright who used history and (Hindu) mythology to make often telling connections with the mores of contemporary world and how they reflected the socio-political mood of the times. This is all the more creditable because his plays proved to be consistently popular and their performances well attended not only in Bangalore and other parts of Karnataka but vast stretches of India as well, over forty years or more.

Modern Indian Theatre has not really been a paying proposition except in small pockets of Bengal and Maharashtra, even there the progenitors usually sustained their Theatre activities doing other jobs: Utpal Dutt financed his highly successful Bengali productions with his earnings from commercial Hindi and Bengali films where he was very popular and well paid. On a smaller scale, Ajitesh Bandopadhyay, a charismatic stage actor and producer also used a similar strategy, when for a while he was a sought after character actor in Bengali films but had not resigned from his lectureship at a Kolkata College. How the brilliant, irascible Shambhu Mitra, sustained himself and his theatre Troup, Bahurupi, is anyone’s guess. Mitra, though, appeared in some Bengali films as an actor and as director was considered good enough to be hired by Raj Kapoor to do Jagte Raho in Hindi, and the same in Bengali as Ek Din Ratre. Having said that one may add, that neither Shambhu Mitra nor Ajitesh Bandopadhyay were professional playwrights, Utpal Dutt did write plays but only three namely Manusher Adhikare, Tiner Talvar, and Jalianwala Bagh actually hold up as gripping plays.

Girish Karnad’s case was different, he was a playwright whose plays were translated and staged in many Indian languages, in Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Malayalam, Telugu, Tamil, Bengali. He was paid a small royalty for the groups that staged them were cash-strapped and their efforts were appreciated by audiences who bought tickets at a very moderate price. Capitalism and its implementation in the financing and the sustaining of the arts, namely the Theatre had not allowed as yet the sale of exorbitantly priced tickets, that has become a norm in metropolitan India in the last decade.

Strange as it may sound, Karnad became a playwright by accident. He wanted to be a poet and write poems in English, win the Nobel Prize for literature; he declared tongue-in-check in a documentary made on him by K.M. Chaitanya for Sangeet Natak Akademi possibly five years ago. He wanted to be with the likes of T.S Eliot, W.H. Auden and others, of course destiny had others plans for him.

He read Mathematics and Statistics for his B.A. at Karnataka Arts College, Dharwad and stood First in the University of Karnataka. This enabled him to proceed to Bombay to pursue a Master degree in Maths and Statistics. It was from there he applied for a Rhodes Scholarship and got it. His father Dr.Raghunath Karnad was not happy with the idea, neither was his mother Krishna bai. His parents were uneasy about their son going off to England (though they would have been proud, in retrospect). They did not know if he would choose to settle down there or marry a white woman!

The result of his parents reservations on his sailing to England (even Rhodes Scholars had to travel by ship in those days) was the writing of the first draft of Yayati, based on an episode from the Mahabharata. The play was written in Karnada, the language of his endeavours in the Theatre. The story of Yayati was of the protagonist being cursed by his teacher Shukracharya for his infidelity. Yayati, then asks one of his sons, Puru, to give him his youth as a sacrifice! Karnad observed in the SNA documentary on him that the idea for the play may have been triggered off by the reactions of his parents just before his journey to England. Yayati’s first draft did not overly impress G.B. Joshi, the publisher- owner of Manohar Granthamala, Dharwad. He told the fledgling playwright that he was moved by the monologue of a dasi (female servant) towards the end of the play! It was polite way of saying try again! A re-write was read by G.B. Joshi and Manoharan, an astute literary man, and the news that Manohar Granthamala shall publish Yayati helped Karnad make-up his mind to come back to India for good.

The Rhodes Scholarship enabled him to read for a PPE (Politics, Philosophy, Economics) Degree at Magdalen College, Oxford. He also became the became the President of the Oxford Students Union, a singular honour for a student. Oxford opened up his horizons and at the same time taught him to focus on his own cultural inheritance. He knew, perhaps because of his training in Mathematics how to clearly and logically.

On return journey to India, by ship he wrote Tuglak, based on his readings on the 13th Century Sultan of Delhi Mohammad Bin Tuglak, also considered by many to be a mad genius who was prevented by his emotional affliction from achieving the social and political harmony he craved. Tuglak, over time became Karnad’s most successful play. Even today, in some corner of India it is being staged in a local language.

The year 1963 saw him back in India and with a job at the Oxford University Press in Madras (now Chennai). He was in the city till 1970 and also became associated with the Madras Players, a group of serious amateurs that did plays in English. Tuglak was staged by them, and shortly after, by Alyque Padamsee in Bombay (Mumbai) also in English. But a translation in Hindustani opened the flood-gates for the play. Ebrahim Alkazi, the Charismatic director of the National School of Drama, in Delhi, staged it at Purana Quila, a dramatic, stark, pre-Mughal fort that gave it both scale and eloquence. The play for no fault of Karnad’s became his calling card over the years-with the uninitiated.

He became a film actor and give a resounding performance as the school master driven mad by the kidnapping of his beautiful wife by the lustful brothers of the local Zamindar. He also gave a fine account of himself in Swami directed by Basu Chatterjee. He appeared as an actor in films and Television, not only because he could test himself in another medium but also to buy the freedom to pursue his activities in the Theatre, namely writing plays.

It has always difficult for playwrights and theatre directors, actors to support themselves financially and pursue their goals with dedication. One was left wondering how Vijay Tendulkar, the famous Marathi playwright manage financially. His plays, even the most successful ones like Ghasiram Kotwal, Sakharam Binder, Khamosh Adalat Jari Heye and Panchi Aesey Aate Hein, would not have brought in substantial royalties as most of the time they were produced by serious amateur groups with limited finances. Tendulkar’s forays into Parallel cinema as a script writer would have brought in steady but modest financial rewards. He did write the scripts for 14 relatively low budget films. Tendulkar managed to support his career as a playwright,y post -1970, as a film script writer.

Karnad, because of his activities in the cinema, and to an extent Television, was able to acquire a certain financial equilibrium to continue with his writing for the theatre. Badal Sarkar, his confrere from Bengal, was the Chief Town Planner of Calcutta. He resigned from this job as it impinged on his activities as a playwright and a theatre producer. He gave up the proscenium theatre for which he had written highly successful plays like Evan Indrajit, Pagla Ghora, Balki Itihas, Hiroshima, Saari Raat. He became an ardent activist of the street theatre, deriving his inspiration from the folk theatre of Eastern India.

Karnad’s making of a playwright was almost an accident. It was when the manuscript of Yayati was vetted with a hawk-eye by Prof. Keertinath Kurtukoti, his exceptionally kind and erudite mentor then living and working in Baroda, he was able to do a rewrite that was acceptable to G.B. Joshi at Manohar Granthamala. It was published in Kannada and caught on quickly. There were stage productions all over Karnataka to begin with, and then all over India.

He observes about his first play: “Oddly enough the play owed its form not to the innumerable mythological play I had been brought up on, and which had partly kept these myths alive for me, but to Western playwrights whom until then I had only read in print. Anouilh (his Antigone particularly) and also Sartre, O’Neill, and the Greeks. That is, at most intense moment of self-expression, while my past had come to my aid with a ready-made narrative within which I could contain and explore my insecurities, there had been no dramatic structure in my own tradition to which I could relate myself.” (Introduction to Three plays, Naga-Mandala, Hayavadana, Tuhlaq, O.U.P. 1994)

Making the theatre his vocation rather a profession was not easy. Karnad had to literally buy his freedom by working as actor in films and Television, directing films and making the most of the Fellowships and Awards that he got. His friend from the Manohar Granthamala days, the truly exceptional translator and fine poet A.K. Ramanujan, had deservedly become a celebrated scholar at the University of Chicago in the US, saw to it that Girish Karnad got the Fulbright Fellowship and wrote Nagamandala and got it produced by the students of the Drama Faculty of the University.

He managed his finances astutely and avoided being called a ‘rebel without claws’! He was certainly not a rebel against the establishment in his formative years. He came from the well-educated Karnataka middle-class, still under the spell of pre-independence idealism. In S.M. Chaitanya’s SNA documentary on him, Karnad says on camera, standing on the steps of an old bungalow in Dharwad that he had lived there as a child with the family when his father was posted in the town, and that Mahatma Gandhi had lived in one of the rooms on the premises! He also adds that he is the present owner of the property.

Dharwad figures prominently in Chaitanya’s documentary for many reason: first, because of G.B. Joshi and Manohar Granthamala, the publishing house that brought modern literature to the Kannada language; second, because it gave Karnad a start and then made him a writer; third, because he came to meet the major literary figures in the language, including Bendre, the great poet who always had an open house, and would happily grant forty five minutes even to an aspiring writer and sent him on his way after his son gave the traditional pinch of sugar.

Dharwad laid the foundation for the young Karnad’s literary future and also gave him, despite his genuine aptitude for Mathematics and Statistics, the confidence to study abroad and become a writer. As a youngster he used to do pretty good sketches of his heroes – the moderns of the English language like T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, and Sean O’Casey, who, incidentally, responded to Karnad’s request for an autographed letter by saying that he (Karnad) ought to become a writer so that others may ask for his autograph!

Dharwad also has the Someshwara temple, which, in popular lore has a connection with antiquity. It was in the tank of this temple that the boy Karnad learnt to swim. It is through this town flows the Shalmali river. He suggested to his wife Saraswati that they name their first born, a daughter, be named Shalmali, rather than Ganga or Jamuna, which were too far away for comfort. Thus the daughter of the Karnad’s was/is named Shalmali Radha.

Karnad’s literary journey had been marked by ups and downs and his quest of finding the right form for the right material been continuous.

His choice of a language for literary expression was curious. Not without a touch of humour. “While preparing for the trip [Oxford], amidst intense emotional turmoil, I found myself writing a play. This took me by surprise, for I had fancied myself as a poet, had written poetry through my teens, and had trained myself to write in English, in preparation for the conquest of West. But here I was writing a play [Yayati] and in Kannada too, the language spoken by a few million people in South India, the language of my childhood. A greater surprise was the theme of the play, for it was taken from ancient Indian mythology from which I had believed myself alienated.” (Author’s Introduction, three plays, Naga-Mandala, Hayavadana, Tuhlaq, O.U.P. 1994)

The choice of such material would not be surprising in retrospect. He had said in the SNA documentary, that his doctor father on his retirement from service in the British Indian Government in 1942-43 was given in a three-year extension and posted to Sirsi, a malaria-ridden settlement in Maharashtra. It was there that he learnt all his “Itihaasa and [tales from the] Puranas” and which stayed with him for life. His exposure to folk theatre was indeed important for his development as a writer.

“In my childhood, in a small town in Karnataka, I was exposed to two theatre forms seemed to represent irreconcilably different worlds. Father took the entire family to see plays staged by troupes of professional actors called natak companies which toured the countryside throughout the year. The plays were staged in semi-permanent structures on proscenium stages, with wings and drop curtains, and were illuminated by petromax lamps.” And then he follows up with the second example: “Once the harvest was over, I went with the servants to sit up nights watching the more traditional Yakshagana performances. The stage, a platform with a back curtain, was erected in the open air and lit by torches.” (Author’s Introduction, three plays, Naga-Mandala, Hayavadana, Tuhlaq, O.U.P. 1994)

He, like Tendulkar and Sarkar, was a product of post-independence modern Indian Theatre that dealt with the social and political problems of the day, each influencing the other. Karnad, in the SNA docu he said he considered Bijon Bhattacharya’s, Nabanna to be the forerunner of modern Indian theatre for it was written as an immediate reaction to Bengal Famine of 1943 in which 3.5 million died. The British responsible for holocaust believed that the figures of the dead were 5 million! There was a bumper harvest that year but the Second World War was on and the Japanese were marching through Burma towards India. All the boats meant for transporting the rice were burnt to impede the possibility of a Japanese invasion, what could be transported to the British army, was done, the rest was left to rot or dumped into the sea or seized by the Marwari black marketers in Calcutta. This digression aside, Nabanna was an epoch- making play. Karnad also criticized Rabindranath Tagore’s plays for being ‘too poetic’ and short on action though he readily admitted that Tagore was a great poet and had influenced important poets across languages in India in his time and a generation later.

The crypto-communist (at least he was one in his youth) Vijay Tendulkar took the Nabanna lesson to heart, and further developed it to his advantage. His important plays are set in contemporary times, and even Ghashiram Kotwal, a period piece about evil doings in public life during the Peshwa period seems like it is talking about India today.

Badal Sarkar, the Civil Engineer from Bengal Engineering College, Shibpur, who also got a Masters in Comparative literature from Jadavpur University in 1992 at age sixty four, began writing about the problems of individuals from an urban middle-class stand point, the classic example being Evam Indrajit, gradually lost faith in the existing socio-political system, including its pseudo-Marxist avatar the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) that ran West Bengal and employed him as Chief Town Planner, a position he surrendered in 1975. He took to street theatre, mainly in small-town and rural Bengal. A new string of plays based on folk theatre forms emerged : to mention a few, Baghala Charit Manas, Dwirath, Ore Bihanga, Manushe Manushe, Janma-Vumi Aaj.

Karnad’s choice of subject to reflect the psychological and socio-political realities of our times is unusual. If Yayati, Hayavadana (based on Thomas Mann’s Transposed heads via Katha Saritsagara) and Nagmandala are set in ancient times, and Tuglaq and The Dream of Tipu Sultan, respectively from early to late medieval times, they do reflect the structure of existing societies and the classes within patriarchy and its values and have a modern ring to them. In each of plays, that number just under a dozen, including the last experimental one, Broken Images, that had an actress interacting with her image on a television screen. He was trying to juxtapose what are considered to be eternal verities with the ethical and moral demands of the contemporary world.

He writes in the introduction to Tale-Danda, set in medieval times that has enormous relevance for our times. ‘’ During the two decades ending in AD 1168, in the city of Kalyan, a man called Basavanna assembled a congregation of poets, mystics, social revolutionaries and philosophers. Together they created an age unmatched in the history of Karnataka for its creativity, courageous questioning and social commitment. Spurning Sanskrit, they talked of God and man in the mother-tongue of the common people. They condemned idolatry and temple worship. Indeed, they rejected anything ‘static’ in favour of the principle of movement and progress in human enterprise. They believed in the equality of sexes and celebrated hard, dedicated work. They opposed the caste system, not just in theory but in practice. This last act brought down upon them the wrath of the orthodox. The movement ended in terror and bloodshed.’’

‘’ Tale -Danda literally means death by beheading (Tale: Head. Danda Punishment).’’

It is difficult to ignore the reverberations these words carry for our times. In the last hundred years or more, there has been a steady erosion of human values: the introduction of mustard gas in World War-I, the dropping of the Atom bomb over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan by the Americans to end World War-II and the holocaust in the same war, that resulted in the most gruesome deaths of six million Jews at the hands of the Nazis. After that all morality and ethics in the world (not excluding India) seems to have collapsed- hopefully not for good. Karnad’s play-writing must be appreciated in this perspective both for its artistry and courage.

He was after all an enlightened believer in rationality, in the efficacy of civil behaviour in civil society and a conscientious citizen and artiste. Towards the end when he was barely able to get about, be it to express outrage along with many concerned fellow citizens after the murder of Gauri Lankesh, and other equally heinous happenings. He proudly carried small placards around his neck that said, ‘Not in My Name!’ and on another occasion, ‘I am an Urban Naxal!’ He knew how to protest in a forceful, civilised and peaceful manner.

Girish Karnad was singularly lucky in finding a soul mate like Saraswati Ganapathy, a doctor trained in New York who married him when he was forty two and became his anchor. Together they had two lovely children; the first Shalmali Radha, a daughter, and the second a son, Raghu. The family served on many an occasion as his emotional and moral compass.

He had resigned as director of Film and Television Institute Pune, in 1975 after the imposition of the Emergency by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi; when he died there was/is an insidious, certainly more dangerous, undeclared Emergency in place with the BJP in power for yet another term. He had faced both events with grace and courage and practised his vocation in the arts with utmost sincerity.