Gender Contexts in Folk Performances: A Study of the Female Performers of Nautanki / Gauri Nilakantan Mehta

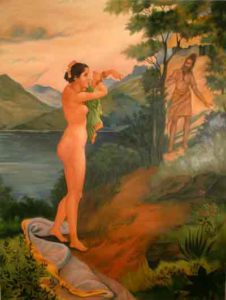

Sage Viswamitra succumbs to the charms of Menaka

Sage Viswamitra succumbs to the charms of Menaka

Source: Exotic India Art

Any context that involves control and exclusion, of the master subject, or the dominant individual or group of the situation, manifests itself through its exclusive performance or by giving high status to them. This can be seen in artistic folk theatre genres. In most situations of aesthetic authority, we can see that the exclusion or low status of one gender, mostly of females, is to establish a total power of the males. My paper will attempt to illustrate this sometimes exclusion and low status of the female performers in folk theatre genres of North India and Pakistan. It proposes to study and analyze the gender contexts of female performers in Nautanki within Uttar Pradesh andPunjab with a special reference to her status in society. Women have been performers since antiquity and many gender stereotypes have been attributed to her. Before we analyze the gender contexts in Nautanki let us briefly elaborate on the historical and social conditions of female performers in folk theatrical forms in India & Pakistan.

Historical and Social Conditions of Female Performers

Women have always been performers in India and Pakistan since the ancient times. The antecedents to dancing girls and courtesans go back to early ages. Statues of theIndus Valley civilization (3000-1500 B.C.) show strong associations with music and dance. A bronze figurine of a dancing girl was unearthed in the ruins of Mohenjadaro, inPakistan, that shows the popularity of performing arts in the Indus Valley amongst females. The figurine has been found in association with a large number of statues of goddesses that indicates that dancing and music must have had close associations with worship and therefore making it popular among women. Although, female worship was considered pure and divine during the Indus Valley Civilization, we have to keep in mind the paradoxical situation of female performers in later ages from fifth or sixth century B.C. onwards.

Women became the sites of orthodoxy as they were seen to be the essential carriers of tradition. According to Mandakranta Bose,

The burden of maintaining order within a family and within society as a whole fell on women…But this was a responsibility within which women quickly became imprisoned by the needs of conserving tradition. Instead of embodying positions of decision -making power and defining order, women became vehicles of orthodoxy. (Bose 4)

By looking at archeological evidences as in sculptural depictions in temples, paintings and early dramatic literature like the Kamasutra (800 A.D.), a treatise on the art of love and lovemaking, many scholars tend to believe that the female performers had a high social standing in ancient Indian society (3000 B.C. to 1200 A.D.). Many literary texts make references to Apasaras or heavenly maidens, also accomplished performers and dancers. They lured heroes and sages from their path of duty, for eg. Sage Viswamitra succumbed to the charms of Menaka. Seduction and allurement hence is an essential characteristic of these courtesans. Dancing and performing hence had strong sensual connotations. Many of the courtesans such as Rambha, Tillotama and Manorama were widely respected and had a high social standing.

However, the relation between these respectable representations and its extension to “real” women can be argued. For e.g. the famous Khajurao caves of Orissa of Eastern India (800 A.D. to 1200 A. D.) depict females playing percussive instruments that later remained in the exclusive domains of the men. We can argue that perhaps these female performers (as shown in the statues) were courtesans, and it was their profession that allowed them to have access to display certain creative skills. The Kamasutra, written by Vatsayana, describes the skills of the courtesan, who was to be well versed in the act of love making but also needed to be equally well versed in music, dance, drama, and painting besides giving them sexual pleasure, in order to please her patrons. Respect given to these courtesans hence had sexual connotations. The paradoxes that are created between real and representations of women has been understood and defined by Dhruvrajan. According to him,

The female principle is worshipped, yet in daily life flesh and blood females are secondary citizens, humiliated depersonalized. The more a woman lowers herself the more she is praised. (Dhruvrajan 100)

This paradox can be seen in other areas of worship as well, despite the fact that female worship is an essential part of the religion of India; females are still in some isolated cases “dedicated to temples” that are called the devdasis. These devdasistraditionally were the courtesans and the dancing girls. These women had a low social status and became victims of prostitution. Devadasis, or servant of god, are ceremoniously married to the gods by the symbolic tying of the necklace around their necks. As they are “married to the gods” they have a social sanction to keep sexual contact with men. The honor of helping with temple shrines such as cleaning devotional vessels and decorating shrines belonged to the devdasis. More significantly, following the heavenly nymph prototype, they worshiped, propitiated and entertained the deities (embodied in images) with dancing. Hueing Tsang, a Chinese visitor to India in the 8thcentury testifies to this well established institution of temple dancers, an Arabian traveler, Al Beruni remarked that about 500 dancers were dedicated in the Somanth temple.

Stigmas have been associated with female performers both historically and socially. For example, as discussed earlier female performers in the past belonged to a set class, the devdasis who were married to the gods. The devdasis who often had to “entertain” men through music and dance and sex thus had some sort of socio- religious- legal sanction because of this “marriage” to the gods. The links between marriage and performance also takes on different levels of meanings as many women performers in India also discontinue their profession after their marriages to men. As tradition places high emphasis on modesty and virtue, many women do not continue with public performances after their marriages, since they would come under the public view and scrutiny. This shows the ambivalence that is maintained towards the female performers in society. Many female performers of Nautanki are married but they belong to certain sects & caste that allows them to perform. They primarily belong to lower caste or lower strata of the society. Thus, there is direct connection between economic status, lower position, marriage & profession that women choose.

With the advent of the Mughals in India we can see the tradition of dancing girls in courts. Performance reached the courts from the sacred shrines of temples. Amir Khusrau, a famous writer in the 12th century A.D. recorded his praise for dancing girls. He also invited them to dance and sing in the marriage of his son. The professional performers were called nutwah, bhugleye, anjari, nat. The actors in Nautanki are also called the nats and the female performers are the natis. Traditionally the only women who acted and performed along with the male counterparts in Nautanki were these devdasis.

The connections between the royalty and performing arts are also a part ofIndia’s cultural history. Often in the past, the court dancers were considered the courtesans, or the nautch girls, and sometimes the performances were performed in the brothels, which were frequented by high-ranking officers of the court and warriors. Wade points to this and argues that the courtesan dancers were considered nautch girls when these performances were relegated to the brothels[1] (126).

A few more examples can make the connections between the royalty and the female performers clear. Grace Thompson Seton, a British woman, who traveled in Indiaduring the early 19th century remarks on the life of “natuch” girls,

I entered the dancing girl quarter, which looked like any other middle class street and good fortune! One of the dancing girls was standing in a doorway, arrayed in white trousers and long yellow diaphanous sari. Her middle and feet and arms were bare. She was not young, nor to my mind, good looking, but she had well developed muscles and supported the entire family on her earnings.

I was told that if I would stay a few days longer, H.H. would arrange a Nautch, but that his best dancer, Moti Jan, was away, having been loaned to a neighboring Raja for a wedding festivity. The maharaja subsides all the dancing girls and therefore controls their actions. (Seton 67)

Written in the early 19th century, this quote shows that dancing was relegated to low class women, wearing “diaphanous clothes”, supporting their families through their incomes from prostitution or “entertaining” the high ranking officials of the court, their actions being controlled by the kings (Maharaja). The king clearly treated the women as possessions since these women were “loaned”. The connection between royalty and dramatic forms therefore seems to have had a long historical connection.

Amorous songs and dances were rendered by these nautch girls. The Calcutta Gazette, a newspaper of 9th June1808 carries one version,

O says what present from your hand

Has reached me save caresses bland

And oh! Was present e’er so dear

As love soft whispers to my ear

Mar in affliction‘s sad decay

How this poor frame wastes fast away

I languish, faint from eve to morn

Nor taste of food one barley corn (Paul, 85).

However, some low class women traditionally performed classical theatrical forms, for example Bhartanatyam and Kuchipudi, two major southern Indian dance dramas. Their primary duty was to perform in the temples as dancing girls, but they could also supplement their family income by serving as prostitutes. Many folk dramatic forms have had the traditional exclusion of females, and only few forms like the Lavani and Tamasha of Western India have included women. These dramatic forms often use camaraderie and sexual innuendoes; therefore, the female performers of such forms do not have high social standing. Therefore, these performances are often “popular entertainment” and quite often-religious themes are not depicted.

Thus, with very few exceptions women were effectively banned from theatrical stage, whether rural or urban, folk or classical. A striking instance of the extensiveness of this ban can be seen in Kathakali, an all male form folk dance drama of south India. Wade observes,

Kathakali was developed in Kerala, on the southwestern edges of the subcontinent, in a region that is traditionally matriarchal and in which women have influential in public affairs and have a reputation for considerable degrees of freedom in society in general. Yet even in this area, so deeply had the ban on women penetrated that Kathakali had been, and remains, an all male form.

(Wade 129)

But, historically & by large it is the female performers who have always dominated the performing art tradition in India and one such form is the Nautanki. Females play a very important role in the Nautanki performances. The next section will analyze the tradition of Nautanki in northern India & Pakistan with detailed references to its gender contexts.

Gender Contexts in Nautanki

Nautanki, a secular semi operatic folk theatrical form of Northern India (Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Rajasthan) and Pakistan (Punjab region) developed from swangand naqqal. Performed in large open spaces and erected platforms, the performance starts with an invocation to the gods or the mangalcharan, accompanied by beating of the drums or the nagaras. The acts have strong and powerful story lines with tales are taken from epics, legends, and important events. The languages employed are common spoken language of the people and the texts are written in Urdu, Braj, Punjabi and Rajasthani. Dances, songs and comic acts make the routine. In the early ages most of the men acted as women in Nautanki, however from the 1930s we see that females performing.

Nautanki is a folk form that has several hidden gender contexts within it. The role of the females, both as an actor and within in the script is intricately weaved in relations to the set historical and social conditions of women. According to Katherine Hansen,

Nautanki theatre as well as myth, epic and popular cinema do not reflect actual social relations, gender differences, and power alignments but rather produce and perpetuate them. They frame paradigms of gendered conduct that assist both women and men in defining their identities, inculcating values to the young, and judging the action of others. (7)

Thus, Nautanki is not only a result but a cause of a particular social gender formation and vice versa. Nautanki plays a very important role in understanding the cultural and social formations of India and helps us to establish the notions of womanhood, & further elaborate gender relations between men and women. Gender roles are also conditioned by the cultural, psychological and social correlates of a society and it clearly defines the rules and expectations to being male or female. Gender roles are thus environmentally conditioned and theatre can play an important part in creation and maintenance of such cultural stereotypes.

The very origin of Nautanki has strong gender connotations. Nautanki, originated in the theatrical play about Shahzadi Nautanki, depicting a woman who was flower light weighing only about 36 gms. Both fair and lovely she was the beloved of Phul Singh. The name of the play is associated with a desirable woman whose hands one could not win. Phul Singh is rebuked by his sister- in- law and he decides to win his pure love despite reproaches. Finally with the help of garderener or malin he gets disguised as his daughter- in- law and he meets his beloved Nautanki and unites with her. The princess here is desirable, bewitching, and a physical need and love for the man. Gender stereotypes can be clearly seen in this play as princess Nautanki is a light weighed virgin woman, untouched and a delicate beauty and Phul Singh`s manhood is rebuked. Heterosexual love between man and woman on both literal and metaphorical levels are emphasized and opposing characteristics between men and woman are thus exalted.

Sexuality is one of the dominant themes that occur in most Sangit texts or the dramatic texts. According to Hansen, incidents (ibid within the performance), images, and characters repeatedly focus awareness on the pleasures and pitfalls of sexuality. (27) The recent sangit text Udal ka Byah (the marriage of Udal), the hero Udal meets his beloved Phulva and wants to marry her and his attempts are thwarted by Narpati Singh and his son, who are Phulva‘s father and brother. Phulva is described to be a lissome, beautiful princess.

The Sangit texts or the play scripts of Nautanki are replete with the female stereotypes. Women in the Sangit texts range from seductresses to honorable virtuous women upholding their womanhood and marriages. In the text Lucknow Ka Lootera (The Dacoits of Lucknow) the protagonist Hamid goes to plunder a rich merchant, whose wife falls at his feet and begs for his life to be spared and when Hamid makes overtures at her, she describes herself as a ‘pativrata’ one who is vowed to her husband. She remarks at his attempts,

Door se baat kar paas mere na aa, yesi kalma mujhe mat sunao. Shok se loot dhan mera le jaiye, ek pativrata ka sat digao nahi

(Talk to me from afar, and don’t say such things to me. You are free to plunder but do not let me break my vow of marriage Akeel, 6)

The female character is rarely seen alone and she is always in connection with the man. The patriarchal society of northern India and Pakistan defines this position of the woman in the texts. At the same time we also see Hamid frequenting a prostitute’s, Chameli Jaan’s “Kotha” or house, who is clearly a seductress and vamp. According to Hansen,

Nautanki poets delight in describing women as murderers, lustful vamps, warring goddesses, and potent sorceresses. Yet they expound an ideology of female chastity and subservience that belies the powerful posture of so many women in their stories. (171, Hansen)

Love, romance, wooing and winning are some of the common themes in the Sangit texts. In the play Siyah Posh, the daughter of the Wazir of Syria falls in love with Gabru. One day while trying to meet Jamal his lover he gets caught and his execution is ordered. The king in his daily rounds hears their love for each other and forgives Gabru who is united with Jamal.

The men in the sangit texts have an exalted position for example in RajaHarischandra, the king bequeaths everything and has to leave the kingdom. He has to earn his living by working in the crematoriums while his wife works as a servant. One day his son dies while playing and Harischandra refuses to cremate his own son as his wife cannot afford the fees. While his unrighteousness is upheld while his queen Taramati often breaks into seductive gestures like swaying her hips and kicking her heels. Hence there are different value additions for males and females.

Many of the acts of the female performers are seductive and amorous songs dances and comic routines make the story go further along. In the play, Lucknow keLootera, a song and dance sequence is enacted between the dacoit Hamid and the seductress and prostitute Chameli. Chameli Jaan sings out loud,

Kya haalat banayi mere gulhjaara

Kyu utra hai chera batao tumhara

Hamid

Na khuch haal pooch meri maahepaara

Is wakt aaya musibat ka maara

(Oh my beloved why do you look so unhappy, don’t ask me why my sweet heart I am in trouble, 15)

Since the performance takes place at 11 pm and continues till the wee hours of the morning, sex and sexuality are recurrent themes. Women performers are often seen in their erotic persona, clearly to please the men and allure their audiences. They hence create as well as fulfill the need “to be looked at.” Mulvey describes this “looked at ness” as seen in many traditional performances,

In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can connote to be looked at ness. (145)

It is this “looked at ness” of the female performers in Nautanki that delegates to her an inferior position as compared to men. Irigaray, the leading French feminist comments on this fact,

Investment in the look is not privileged in women as in men. More than the other senses, the eye objectifies and masters. It sets at a distance, maintains that distance. In our culture, the predominance of the look over smell, taste, touch and hearing has brought about an impoverishment of bodily relations. The moment the look dominates, the body looses its materiality.[2] (70)

In modern days, Nautanki is characterized by lusty singing, dancing and women often performing to the tunes of popular film songs and mimic erotic dances. The main objective of the performance is to entertain and delight their audiences. A kind of liaison is thus created and developed. There is hence an exchange of desire, a kind of courtship between the audiences and the performer that is born. The dancing and singing of submissive females appeal to the masculinity of the audiences. Therefore the performances of Nautanki, creates an imbalance for the female performer, negating her position and demeaning her persona and establishing the total power nexus of the males.

To conclude, the Nautanki performance creates different values for men and women, and makes a comment on existing socio- economic & political situation of female performers. Nautanki thus creates many contradictions and conflicts for the female performer however one cannot negate or undermine its creative values and inputs into the rich cultural tradition of India and Pakistan. Nautanki despite its strong gender biases is one of the leading folk theatrical forms that have lent its hand into many other popular mediums of communication such as films and songs. This form thus needs to be studied and understood in all aspects of its rich diversity in terms of its acting style, rich sangit texts, music and costume.

Readings:

- Nevile, Pran. Nautch girls of India: Dancers, Singers Playmates Ravi Kumar Publishers: New Delhi, 1996

- Prakash, Sinha. Lorang: Uttar Pradesh. Hindi Sansthan: Lucknow, 1990

- Hanna, Judith Lynne. Dance Sex Gender: Signs of Identity, Dominance, Defiance and Desire Chicago UP: Chicago, 1988

- Thomas, Helen ed. Dance Gender and Culture McMillan Press: London, 1993

- Gargi, Balwant. Folk Theatre of India Rupa and Co.: Delhi, 1991

- Vatsyayan, Kapila. Traditional Indian Theatre National Book Trust: Delhi, 2005

- Hansen, Katherine. Grounds For Play: The Nautanki Theatre of North India Manohar Publications: Delhi,1992

- Ghadially. Women in Indian Society Sage publication: New Delhi, 1988

- Dhruvrajan. Hindu Women and the Power of Ideology Bergin and Garvey: Mass, 1989

- I C Owens. Feminist and Postmodernism. Pluto press: London, 1985

- Mulvey. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen vol. 16 no. 3 1975

- Wade, Bonnie. The Status of Women in the Performing Arts of India and Iberia: Cross-Cultural Perspectives from Historical Accounts and Field Reports. Blacking, John. Ed. The Performing Arts: Music and Dance. Hague: Mouton, 1979

- Seton, Grace. Yes, Lady Saheb” A Woman’s Adventuring with Mysterious India. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1925.

- Painter, Akeel. Lucknow Ka Lootera Mumbai publications: Allahabad (sangit text)

- Painter, Akeel. Udal ka Byah Mumbai publications: Allahabad (sangit text)

[1] The British described these courtesans or the dancing girls as natuch or dancing girls. Nautch is derived from the hindi word Natch.

[2] Irigaray cited from I C Owens Feminist and Postmodernism. Pluto press: London 1985