Barun Chanda’s Murder in the Monastery: A Mini Review / Raj Ayyar

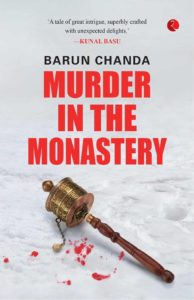

Barun Chanda’s ‘Murder in the Monastery’: A Mini Review

‘It rained unseasonably in the afternoon–a sudden shower that came without warning. High winds moaned through the glass panes of windows. People ran indoors.

Blue streaks of lightning zigzagged through dark clouds, freezing the raindrops mid-air. Then came the hailstorm.

In no time at all, the courtyard turned snow white.

Gusts of wind made the prayer flags flap loudly in protest.’

–Barun Chanda: Murder in the Monastery.

Unfortunately, the sun comes out a little too soon, just after the Gothic build up!

I have mixed feelings about this murder mystery set in a Tibetan Buddhist monastery high up in Sikkim, with splendid Himalayan views, and a cast of eccentric characters some murderous.

I’d say–one thumb up, and one thumb down for Barun Chanda’s second thriller translated from Bengali to English.

I don’t know why Chanda, a maverick actor (even had a role in Satyajit Ray’s ‘Seemabaddha’), cum executive cum author is considered the daddy of the Bengali adult thriller. Though Satyajit Ray wrote his Feluda mysteries for kids, I suspect more adults than kids read them these days. Ditto for Saradindu Bandyopadhyay’s Byomkesh Bakshi.

The text situates itself initially within the whodunit genre, with detective Avinash Roy and his sidekick Pradyot, surrounded by a host of suspects, many of them European expats of dubious credentials. However, it flip flops over to a Dan Brown style thriller, complete with a missing secret manuscript about Jesus spending time not during the missing years, but after his alleged death, at a Buddhist monastery in Kashmir.

The manuscript zealously guarded in a basement vault by the good Buddhist monks at Chanda’s Dengziang monastery in Sikkim. Yet it vanishes leaving a distraught abbot, tense monks running around, and two murders linked to the missing manuscript.

Chanda, unlike Dan Brown, manages a credible, minimalist diplomatic secularism–though the murderer is s hired goon of some Christian sect or other, Chanda does not point fingers at the Catholic church or Opus Dei, a la Brown in ‘The Da Vinci Code’.

I liked the erotic undercurrents in the novel overall–the steamy one-night stand between Miriam the fair-skinned Coorgi Catholic nun novice and Tenzing, the fully grown adolescent Buddhist monk novice, is deliberately understated and leaves the reader’s pornographic imagination to fill in the details.

However, Chanda is resolutely heterocentric, and his detective marginalizes suggestions of monkish gay sex with a disapproving homophobic sniff, that is implied, not expressed.

Well worth a read at an airport, or on a long airplane ride.

—Raj Ayyar