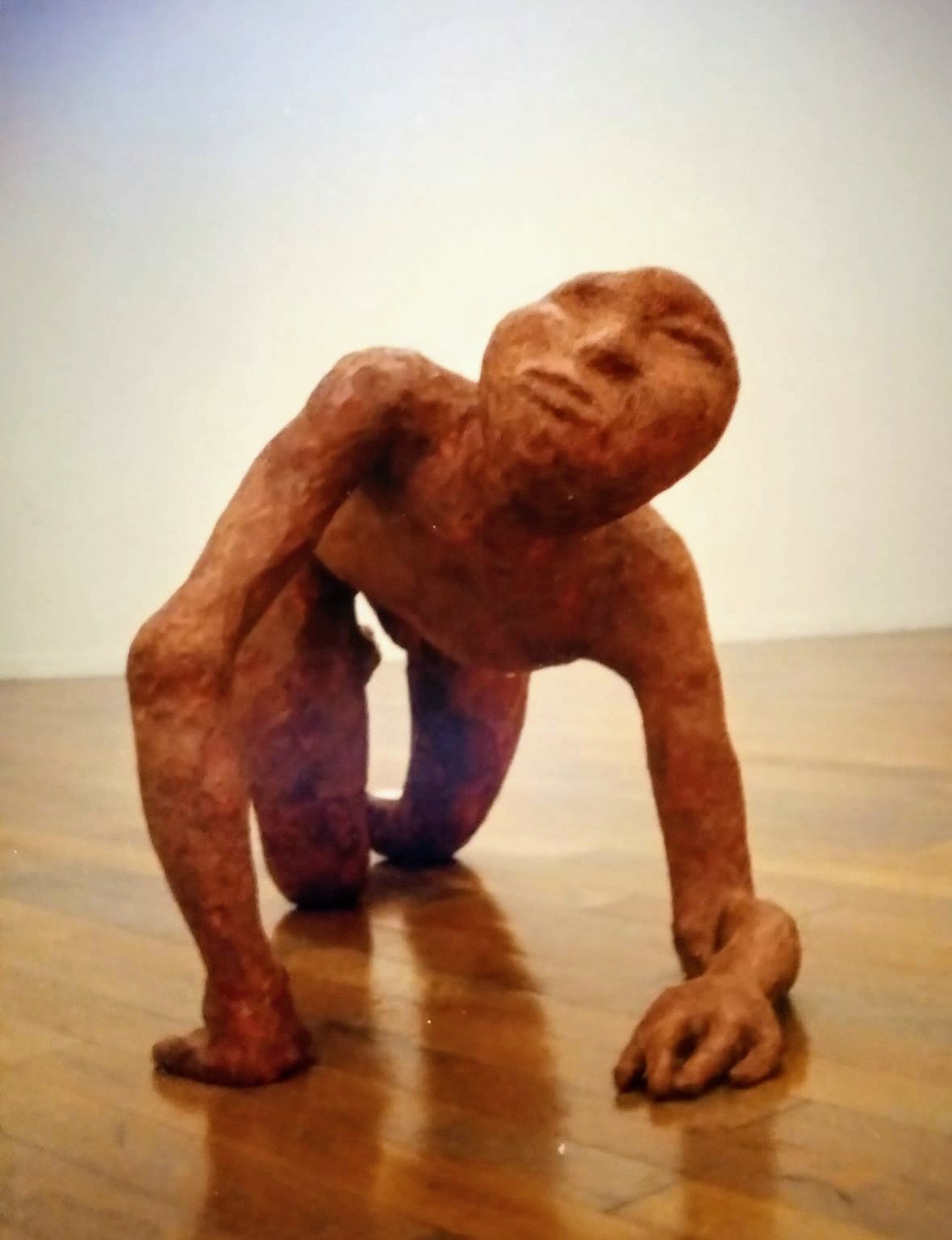

The World on its Hands and Knees | Archana Hebbar Colquhoun

A Sculptural Representation of Covid-19

The timeline of the global pandemic of the coronavirus and its deadly manifestation as Covid-19 needs no introduction. The scale and the enormity of the destruction caused by Covid-19, the speed at which this large-scale culling of human beings – not in anyone’s living memory – with no resolution in sight, has brought the world down on its hands and knees.

As a visual artist, my mind could only think in images in order to make sense of this holocaust-like situation and there rose from my memory a sculpture of a crawling man, which I had made more than three decades ago.

I made this sculpture in 1987 after I moved to Tokyo and I had absolutely no desire whatsoever to write about another artist’s work, having worked as an art critic in New Delhi. I decided to change the course of my life and become an artist. I started working in a small back room of my two-room apartment in Tokyo. I bought large blocks of a caustic material – polystyrene, to carve life-size figures. All of the figures had irregularities in their physical form and each image/figure was based on a specific person I had seen, moving around on the streets of Calcutta (of the early to-mid 80s). The sculpture that I will be referring to is my second life-size sculpture that I ever created. I hadn’t studied sculpture in Baroda, but my seven year-long study of art history enabled me, without my knowledge, to simply pick up the necessary tools and material and create sculptures of people, based on realistic figuration, a task for which I had no prior training. The sculptures were made out of a poisonous material, taking on human forms with congenital or deliberately created ‘malformations’ in the body, for which life models are not readily available, unless the very person I saw posed for me as a model. This meant that the forms had to be drawn purely from my memory along with a bit of imagination to crystalize the form. But, earlier I did say that these sculptures were based on actual people I had seen. I made a set of five figure sculptures, including one of a new born baby. I was, at that time, almost certain that I would not have a child – I wasn’t made to be a mother. This has been proven wrong.

In this set of five figures there is one exception. This work is purely from my imagination, a form I have never ever seen in real life, and which is based on one of my life experience that to this day makes its presence felt in my conscious and subconscious mind with decreasing intensity over the years.

I will now come to the sculpture, which is the subject of this article and which is the second one in the series of five sculptures.

Although the figure is based on someone I actually saw on a Calcutta street – and froze for a few moments when I happened to set eyes on him – and the memory of him to this day is still a strong presence, I needed to use models to carve a sculpture of the man. The person I saw should have been provided medical help, perhaps earlier on in his life, given equipment that was suitably devised for his particular needs, and an opportunity for social integration. It was the lack of any form of institutional support for the man, left to his own devices to function on the streets that stopped me in my tracks when I encountered him, while other pedestrians walked past him and took no notice. I didn’t have to stand there studying the form of the man to memorize his stance and mobility. He was not a spectacle for me but an individual, just as myself, who happened to catch my eye only very briefly but that brief encounter has had a lasting impression on me. It is a mystery to even the most seasoned practitioner of the visual arts as to why a certain image enters their consciousness and makes a home for itself in the deep recesses of their memory.

Polystyrene is the medium of all five sculptures in the group. The medium itself symbolizes the near-evil destructive potential of the myriad man-made materials enveloping the earth, in an embrace of death.

The figure, as mentioned earlier, although drawn from memory so vivid as to compel me to give it tangible form, required that I use life models who could hold the twisted posture of the figure that I wanted to carve. A model was necessary, especially in the case of this sculpture, for me to be able to study the skeletal framework of the figure that would lend itself to such contortion, observe the stress, and tension of the musculature in the limbs and the torso, with the neck craning upwards so the head could rise up to look at what is above the eye level.

The sculpture is of a man, who can move only by crawling on his hands and knees, his head trying perpetually to look at what could have been and what he may have been able to attain in his life if he had been blessed with a skeletal frame and an arrangement of limbs that would allow him “normal” physical movements. His limbs were skinny and bent in unexpected places and the angles fixed and rigid.

Yes, this is a sculpture of a man (my models for the sculpture being both male and female – friends of mine) the man crawling on his hands and knees, almost entirely without clothes, dragging his miserable collection of body parts along the rough, dusty, broken stones of a pavement but he appeared determined to continue on with his life.

This figure of a crawling man, almost helpless and completely without hope of any improvement in his circumstances, symbolizes to me the state that the greatest of world leaders and every single human being is reduced to today, by COVID-19. The coronavirus has brought the whole world down to its hands and knees.

In my next article in the series on Covid-19, I will take up the issue of “Social Distancing,” a term that is problematic due to its various negative connotations. The subject of the article will be another one of my sculptures from the series of five, titled “Seated Man.”