Small is Beautiful / Keval Arora

When listening to people speak of how difficult it is today for theatre groups to survive, and therefore of the feasibility of theatre itself, I find it difficult to share the general air of regret that envelops such discussions. Sure, it isn’t easy to produce plays on a regular basis, especially for those who intend to make a living solely off performance. But it probably never has been – at any rate, far longer than many doomsayers would care to remember. Theatre today is pushed into a corner. The sooner we accept that fact as a given condition, and make our adjustments and interventions with such shrinkage in mind, the better we will be able to renew our appreciation of theatre’s strengths and possibilities. Hankering for a return to glory days is a nice theme for lazy winter afternoons, but not for the evenings when rehearsal time is upon us.

Is this an unfounded optimism? I think not; in fact, it’s not even an ‘optimism’ in the first place. If anything, it’s impatience with the habitual passivity, the automatic funereal tone of the way we think about our work. If ‘the death of the theatre’ will ever come to pass (the way in which there has been talk for some time about ‘the disappearance of the playwright’), I suspect it’ll come from the failure of its aficionados to look forward from the present. By this, I do not mean that we accept the current scenario as a value in itself, for there is no need to infect our appreciation of theatre’s function with the market-driven models of today. But, we do need to see where we can go from here, rather than talk as if our future lies in returning to the past. I sometimes hear the 70s being spoken of with some fondness. But I began watching theatre in the 70s, and I don’t ever remember feeling free of the same anxieties then, the way retrospection today persuades us to believe. Unfortunately, for many people, the past has always been a better place, much in the way that the dead have only good things said about them.

There is always an audience available for plays. Correction: there will always be an audience available for plays. In the several years that I have been attending performances, I have not come across too many instances of plays running to absolutely empty houses. It is another matter that some plays that deserved fuller houses did not get them, while others that ought to have been less popular had spectators arriving in droves. (Given the troubled state of theatre attendance and solvency, comments on such anomalies were rarely aired aloud, being more a matter for internal envy rather than for public pride.) The point is not whether there is or isn’t an audience for theatre; rather, what is our expectation of an audience – what is the minimum number required for spectators to be regarded as an audience?

It is essentially a numbers game. An ‘empty house’, or a ‘FULL House’, is a relative term, relative to the capacity of the auditorium and varying in tone according to the amount paid out as rental. Take a 500-seater, sell 50 tickets and you have a cavernous hole that depresses producers, deadens actors and embarrasses spectators by its silence. Place the same 50 people in a space designed for 75, and there is no way you can remain immune to the palpable buzz of togetherness. Performances in smaller spaces get charged in a manner that is impossible to replicate in the bigger auditoria. Amidst all this talk of dwindling attendance, why then do we insist on opting for large auditoria as our venues?

Admittedly, 50 tickets (not a terribly inspiring number in itself) is still only 50 tickets, irrespective of whether the number left unsold is 450 or 25. In the 75-seater auditorium, it still adds up to the same absolute number of spectators, and generates roughly the same amount of income; so why is this supposed to be a rosier picture? Before I am accused of dipping into the bag of ingenious tricks perfected by finance ministries to manufacture their statistics of health, let me quickly say that it is the economics of play production that makes me see in smaller venues an answer to our woes in the theatre. That is, even if we disregard the value of such space in terms of performance and spectating, there are still financial advantages to working in the 75-seater auditorium.

Smaller theatres cost much less to rent than the bigger ones. As hall rentals form a substantial and recurring portion of production expenditure, any reduction in this area will contribute substantially to financial health. What most theatre groups do when they book the 500-seat auditorium is express a hope for attractive returns; what they end up doing is investing in 450 empty seats.

Small auditoria cannot of course meet the needs of all plays. Some texts require the machinery of large stages, or the space required for big casts. Such productions will necessarily have to exclude the 75-seater auditorium from its range of options. But, the majority of plays are geared for, or amenable to, intimate stagings. Especially contemporary plays, for playwrights too have wised up to the need to cater to groups with few actors and limited means.

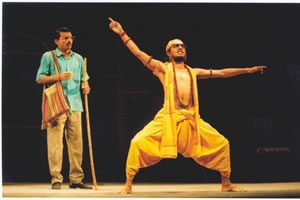

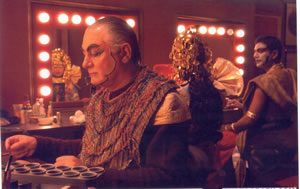

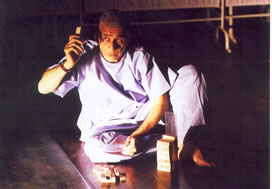

The other advantage to performing in small spaces is of course enough to make such venues attractive even if they were by some quirk more expensive to hire. In the small theatres, the proximity of the actor to the spectator confers an intensity and directness upon performance that is difficult to match in the anonymity of larger spaces. When I think of performances that got under my skin when I saw them and are still with me now, I am struck by how many of them were played at intimate venues: Woyzeck and Adhe Adhure at the NSD Repertory’s Studio Theatre, Nagamandala at the Prithvi in Mumbai, Mother Courage at the Modern School Gym…. How much of their magic owed to the setting in which they were performed, whether that quality would have been preserved had they transferred to larger, more conventional spaces, are difficult speculations. Productions are conceptualised with physical spaces and visual relations in mind; the best actors play within the altered chemistry that proximity brings; and therefore it is naïve to think of theatre productions as manufactured items that function with the same stability no matter the shop in which they are sold.

Such intensity may not always be comfortable or desired. First time actors quickly experience the disorientation of performing in close-up, and learn to tone down volume and gesture, cull emotion of its theatricality, and re-locate their focal centre within themselves; in other words, they learn to work pretty much as actors do for a camera. Spectators can sometimes be discomfited too, especially when actors fail to work within the reduced scale – as in the case of performances at the now unavailable for theatre IHC Basement, where actors sometimes project their voices and bodies as if they are addressing back rows 75 feet away, they effectively end up bombarding the audience rather than speaking to it. But, there is no denying that special feeling of being sucked into the fiction when spectators are virtually thrust into the performance space.

This sensation is heightened in those small theatres that are not designed as the poor cousin, mimicking the proscenium methods and apparatus of the Big Brother. The real strength of the small stage lies in the flexibility that reduction in size brings – in its potential to leave seating and lighting arrangements to the director and the set designer and to let them determine the physical and visual relation best for their production, as in the Bahumukh theatre at the NSD. However, even when the audience seating area is physically demarcated and fixed (as in the case of Bombay’s Prithvi Theatre and the NSD Sammukh Theatre), the fact of being seated at an informal distance, at virtually the same level as the actors (the Bahumukh) or at scattered angles (the Prithvi) makes watching a performance here very different from the regular experience. The effect of a heightened intimacy, a direct (and sometimes even private) connection with fictional space, powerfully underscores theatre’s function as a persuader.

That’s why it’s not the same thing to being seated in the first row of a regular auditorium. If you’ve had the misfortune of being stuck up front, you’ll know what I mean when I say that it’s possibly the worst row in the house. Great for being looked at perhaps, especially if you make arriving late a habit; but lousy if you’ve come to look at the show. The angle at which you have to look upwards is all wrong (especially at the Kamani), and it’s virtually impossible to take in the width of the stage without feeling that you’ve wandered into a tennis match. (Great exercising for the neck, of course, so let’s not trash the hidden benefits of the theatre?) Watching a street performance in the round does not produce a similar effect of intimacy either, though there is little physical distance between the actors and spectators, and the performance area does not call for callisthenics of any sort. I’d imagine that it is the ‘public’ nature of such theatrical practice that overlays all such ‘proximity’ with a public air.

Where are such performance spaces in Delhi? The SRC Basement is the first name to crop up, but that apology of a performance space merits first mention only because it’s been around a long while – no longer, though: it closed down some years ago – and a home to several theatre groups. There is no other comparable space. The Basement Theatre at the IHC had begun to witness a lot of activity, but that was mainly because of a dearth of venues at that price. For the IHC Basement to have fulfilled its potential, it had needed to alter the performance space to allow multiple-entry access to actors, to install a lighting grid that covered the entire space and to install more lights of much lower wattage. I speak of all this in the past tense because today the IHC Basement Theatre is unavailable to theatre performance courtesy the objections of some municipal committee. Other spaces such as the Sammukh and the Bahumukh theatres are performance-friendlier spaces but unfortunately available only to programmes run by the NSD.

That makes this discussion on the merits of small performance spaces a purely academic one. The small auditorium, like so much else in the theatre, sadly exists more as idea than as fact.

An earlier version of this article was first published in FIRST CITY (November 2001)