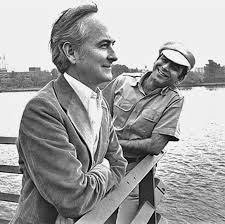

Ismail Merchant: Film Producer Extraordinary / Partha Chatterjee

Ismail Merchant’s passing away on May 25, 2005 marked the end of a

certain kind of cinema. He was the last of the maverick film producers with

taste who made without any compromise, films with a strong literary bias

which were partial to actors and had fine production values. It is sad that he

died at sixty eight of bleeding ulcers unable to any longer work his

legendary charm on venal German financiers who were supposed to finance

his last production, The White Countess, which was to have been directed by

his long-time partner James Ivory.

Merchant-Ivory productions came into being in 1961 when, Ismail

Merchant, a Bohra Muslim student on a scholarship in America met James

Ivory, an Ivy-leaguer with art and cinema on his mind, quite by accident in a

New York coffee shop. The rest as they say is history. Together they made

over forty films in a relationship that lasted all of forty-four years. A record

in the annals of independent filmmaking anywhere in the world.

Ivory’s gentle, inward looking vision may never have found expression on

the scale that it did but for Merchant’s amazing resourcefulness that included

coaxing, cajoling, bullying and charming all those associated, directly and

indirectly with the making of his films.

Merchant-Ivory productions’ first venture was a documentary, The Delhi

Way back in 1962. The next year they made a feature length fiction film The

Householder in Black and White. It was about a young college lecturer,

tentative and clumsy trying to find happiness with his wife from a sheltered

background. Ironically the script was written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, a

Jewess from Poland married to a Parsee Indian architect. James Ivory who

knew nothing about the subject did a fine job of directing his first real film.

He had made a couple of pleasant documentaries earlier.

The crew was basically Satyajit Ray’s, a director who was already being

acknowledged the world over as a Master and whose Apu trilogy, Jalsa

Ghar (The Music Room) and other films had made a lasting impression on

international audiences and critics. His cameraman Subrata Mitra, also

lionized, photographed The Householder which was designed by Bansi

Chandragupta, the most resourceful art director in India, trained by Eugene

Lourie, who created most evocative sets for Jean Renoir’s The River, shot in

Barrackpore, near Calcutta in 1950.

The success of the Householder in the West was largely due to the efforts of

Merchant’s energy and drive. He wooed the Press which responded warmly

almost to a man. His film went to those distributors who could give it

maximum exposure and a decent royalty. His task was made easier by the

rousing reception accorded to Satyajit Ray’s lyrical cinema to which

Merchant Ivory’s maiden effort owed clear allegiance.

Their second film Shakespearewallah (1965) had an elegiac tone which

added poignance to its lyricism. It was a fictionalized account of a true story.

A well-known English theatre couple Jeffrey and Laura Kendall who play

people like themselves in the film actually ran a peripatetic theatre company

in the British India of the 1930s, and 40s. The troupe got into grave financial

difficulties when their audience endowed anglicized Public schools and

Country Clubs whose members belonged to flourishing British owned

mercantile establishments suddenly lost interest in all things English. The

purple patches from Shakespeare done by the company, which also had

some Indian actors in real life, as in the film, no longer interested people,

whose enthusiasm for culture could best be described as ephemeral.

Only the romance between the young daughter of the English couple and an

Indian rake was fiction. The performances were first-rate and Felicity

Kendall as the daughter was moving. Beautifully photographed in B/W by

Subrata Mitra and scored by Satyajit Ray, whose music sold half-a- million

long-playing records, Shakespearewallah was a huge success in America

and Europe. Ismail was only twenty-eight years old when he produced his

second feature film. He proved himself to be a man of fine taste, possessing

the ability to grasp an opportunity when it presented itself.

In retrospect, one can say he best illustrated the idea that artistes are a

product of history. They reflect a certain spirit of their times—so too with

Ismail Merchant and his alter ego, the director James Ivory. They came at a

turbulent moment in Western politics, culture and cinema. The French New

Wave was about to peak and had already revealed the staggering

possibilities of film narration. Filmmakers as disparate in temperament as

Alain Resnais, Jacques Tati, Robert Bresson, Jean Luc Goddard, Eric

Rohmer and Francois Truffaut had enriched film language and proudly

declared it an art form to be taken as seriously as literature, music, theatre or

the plastic arts. In the Anglo-Saxon world classical cinema was in its last

throes, and its greatest master John Ford was unemployed, ignored by know

all young men running Hollywood. There was a niche for a different, gentler

kind of storytelling and Merchant-Ivory films filled it.

Their early productions were devoted to selling exotic India abroad and who

could do it better than Ismail? The third film that Ismail and James did

together was set in Benares. The Guru (1968) had the contretemps of a

famous classical sitarist with his two wives—one traditional, the younger

one modern, as its focal point. Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation

had swept across America promising deliverance from the ravages of greed

and avarice brought by relentless capitalism. Recognizing this phenomenon,

the story included as a catalyst an English pop star and his girlfriend. India

and its contradictions, the musician attracted to modernity but comfortable

only when maintaining status quo, his celebrity English disciple and his girl

both hoping to find peace in the holy city where the ustad lives, all this

constituted a visually interesting but not witty or incisive narrative.

Energetic promotion prevented the film from being a dead loss. While it did

not make a reasonable profit, it made money—only some.

Bombay Talkie (1970) the fourth Merchant-Ivory offering was about an

ageing male star, who was unable to cope with his own life, fame that was

soon going to elude him, and the unreal world of Hindi cinema. Apart from

Zia Mohyeddin’s powerful performance as an ignored lyricist, and Subrata

Mitra’s camerawork, including a long bravura sequence at the beginning,

there was little to recommend about the film. Utpal Dutt, whose dynamic

presence held The Guru together, was just about adequate as a harried film

producer. Shashi Kapoor who was so good in the first two films, looked tired

here.

Bombay Talkie did nothing for Ismail Merchant or James Ivory. Two films

in a row that barely made money, put the company under financial strain.

For the first time in his life, Ismail was forced to deal with the unyielding

Jewish moneymen of New York on less than equal terms. The experience

marked him for life and made him a skinflint. His old friend and colleague

Shashi Kapoor, remarked on television that Ismail did not like paying any of

his actors and technicians anymore than he absolutely had to.

The Savages (1973) was made in the U.S. in an old colonial Restoration

mansion, in Scarborough, forty minutes away from New York. The old place

and the jungle nearby gave Ivory the idea of bringing in jungle dwellers

from Stone Age into the twentieth century. An object the “Savages” had

never seen before, a coloured ball, suddenly descends in their midst. The

retrieval of it by people from the modern era provides material for a

potentially hilarious and wise film. The script based on an idea by Ivory and

not written by Jhabvala, lacked subtlety and humour. Although the director

saw it as a “Hudson River Last Day in Marienbad”, his film had all of Alain

Resnais’s intellectual tomfoolery but none of his poetic intensity. Merchant

understood right away that original material was not the duo’s cup of tea,

and thereafter relied, exclusively on literature to provide the ballast for their

films.

After The Wild Party (1975), a sincere but inept attempt to recreate the

excesses of the Jazz age in sinful old Hollywood, an undertaking the

inspiration for which may well have been the jewelled prose of F. Scott

Fitzgerald, Merchant Ivory production was again in dire straits. Certain

critics including Pauline Kael of the New Yorker even called Ismail and

James a pair of amateurs. The energy that drove their first two films seemed

to have deserted them.

Merchant would have to turn things around speedily before America wrote

them off. Roseland (1977) set in a real ballroom of that name in New York

where people come to shed their loneliness was too civilized, too tentative to

move viewers. Although it had a solid cast led by old-timer Teresa Wright

with Lou Jacobi, Geraldine Chaplin and Christopher Walken who featured in

the three inter-connected episodes, it was lacking in drive. Ivory seemed to

have found a cinematic language that was true to his temperament, but it still

needed polishing. The opportunity came with an adaptation by Ruth Prawer

Jhabwala, who else, of Henry James’s The Europeans (1979). The

interiorized pre-modern drama was just what Merchant Ivory productions

needed. Accolades followed and actress Lee Remick’s performance in a

pivotal role was greatly appreciated. It was more than a success d’esteeme.

People in large numbers bought tickets to see it. Ismail and James had

finally made it to the front rank of American and European filmmakers.

They were still in their late thirties.

The following year in 1980, they tried their hand at an experimental musical

Jane Austen in Manhattan about various troupes wanting to perform a 19 th

century manuscript by Jane Austen written in her childhood that was

recently discovered. It starred Anne Baxter, who shot to fame thirty years

earlier as Eve Harrington in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All about Eve and

Robert Powell, also a contemporary of hers. Made on a shoestring budget of

450, 000 dollars, it was like the proverbial curate’s cake, good in parts.

Quartet (1981) based on Jean Rhys’s despairing existentialist novel about

bohemian Paris in the late 1920s starring Isabelle Adjani, Maggie Smith,

Alan Bates and photographed in luminous low-key by Pierre L’Homme,

cinematographer to Jean Pierre Melville, father of the French new wave, was

a feather in James Ivory’s cap. It was possible only because of Merchant’s

exceptional organizing skills and uncanny judgment of the artistic and

commercial climate of Europe and America.

There was indeed room then for a quieter, more reflective kind of cinema in

the English-speaking world, especially after Hollywood had expended its

energies on mainly violent moralistic dramas and thrillers. The ‘serious’

French cinema, thanks or no thanks to the brilliant cinematic combustions of

Jean Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette and Chris Marker had been

forced to virtually abandon the linear narrative, with the notable exception of

Francois Truffaut and, more so, Jean Pierre Rappeneau. It secretly welcomed

well-told stories from any part of the world. Satyajit Ray’s films and those

of Merchant Ivory found favour with discerning French audiences,

principally in Paris.

Ismail and James returned to the twilight world of Maharajas and ‘illicit’

love; the consequences of one is probed by a young Englishwoman in Heat

and Dust (1983). Julie Christie is the woman who comes to India to

understand her late grandaunt’s affair with a Maharaja (Shashi Kapoor) and

falls in love with a handsome youth (Zakir Husain) and gets impregnated by

him. It was a big hit. Though Merchant-Ivory had to take a lot of flak from

the critics. Ismail’s logic was clear. Someone had to pay for the homes and

offices in London, New York and Bombay (now Mumbai).

The next year it was time to regain critical acclaim and the affections of a

loyal audience. Once again it was Henry James to the rescue and his

Bostonians was Merchant Ivory’s key to success. It restored their prestige

and gave them an unspoken right to adapt works of ‘difficult’ writers for the

screen.

E.M. Forster, a great but not popular English writer was next on their

agenda. A Room With a View (1986) featuring Daniel Day Lewis, son of

poet C. Day Lewis, Helena Bonham Carter, Judi Dench and Maggie Smith,

was the first attempt to find a cinematic equivalent to Forster’s prose which

was at first glance unsuitable for an audio-visual interpretation. There was

too little physical action in his writing—A Passage to India and Where

Angels Fear toTread have short bursts of it—most of what occurs was in the

minds of his characters. Merchant and Ivory won a fair bit of critical

acclaim, and made decent amounts of money on it.

Their films were always about people, trying to find

themselves—deliberately or not. The price they pay to arrive at an

understanding with life is usually heavy. Most often they are aware of their

dilemma; however, there are exceptions. Does Stephen, the faithful old

butler in Lord Darlington’s household really comprehend what an unfair

hand he has been dealt by his former employers in Remains of the Day

(1993)? Only Miss Kenton, the housekeeper, who like Stephens is now

without a job, seems to know despite a stoic acceptance of her fate.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel helps Ivory make perhaps his finest film: a quiet,

understated, but never the less powerful depiction of class and privilege in

pre-war England. The same pair of actors Anthony Hopkins, and Emma

Thompson from their Forster triumph of a year earlier Howards End were

repeated to great effect in Remains of the Day.

Howards End (1992) was set during the economic depression that swept

Europe and America in the late 1920s through the mid-1930s. It was about

naked abuse of power and ruthless assertion of privilege. Anthony Hopkins

as an aristocrat with a roving eye is riveting but it is the women who elicit

both respect and sympathy. Emma Thompson and Helena Bonham Carter as

sisters from the middle-class whose trust is betrayed heartlessly by the

aristocrat, culminating in the murder of a male friend of the younger sister,

with their accurate reading of social situations, throw the film into a political

perspective which needs no polemics to comprehend.

If this article is as much about Ivory as it is about Merchant then there is a

reason for it. They were joined artistically at the hip. One was at his best

only when complementing the other. It was Ismail who encouraged, even

inspired James, to stretch himself to discover his true métier; to take risks

with complex literary texts that were difficult to film but could be

immensely rewarding once an effective method was discovered.

Who for instance had dared to film primarily uncinematic authors like

Forster and James in an Anglo-Saxon cinema? Who dared to gamble and

win but Ivory egged on by Merchant. To make meaningful cinema out of

texts with sub-terrainean relationships hidden under a patina of good

manners, where what was being said and done often meant the opposite, was

no mean achievement.

This kind of interiorized drama was also the highlight of Mr and Mrs Bridge

(1990) with Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward playing the eponymous

couple. Set in Kansas City during the Depression, it travels over two

generations to Paris. The inclusion of the Louvre as a location was a

masterstroke, made possible through Ismail’s penchant for legerdemain.

Apart from Newman and Woodward’s stand out performances as a rich

couple stultified by time unable to understand the changing world around

them, there was the elegant presentation of a difficult idea. Adapted from

two novels by Evans Connell, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge was a critical as well as

a commercial triumph.

Ismail had once said in an interview that he had brought in Jefferson in Paris

(1995) for five million dollars; a feat beyond any producer, independent or

backed by a Hollywood studio. To make a period piece about the second

president of the United States and him courting his future French wife, for

such a sum was a well nigh impossible task. The film was panned despite

Nick Nolte’s caring performance and Pierre L’Homme’s telling

photography.

It was only a year earlier in 1994 that Ismail had made his own debut as a

director in feature films. It is not that he had never been behind the camera

before. His short The Creation of Women (1960) had been nominated for an

Oscar in its category and later Mahatma and The Mad Boy (1974) of twenty-

seven minutes duration was highly acclaimed. It is quite possible that he had

grown tired of fundraising for large projects that had to be reasonably

budgeted to be commercially viable. He wanted to do a small, intimate film

he could call his own. He chose Anita Desai’s novel In Custody to do as

Muhafiz in Urdu. He got Desai and Shahrukh Husain to write the screenplay,

which was set in contemporary Bhopal. Noor, a huge, custardy man, a once

important Urdu poet is on his last legs, dying of adulation heaped on him by

sycophants much like the rich food he so enjoys. He lives with his two

wives, one like him old but unlike him reliable and the other a young,

opportunistic tart rescued from a local brothel and the mother of his son.

Devan, a young Hindu lecturer devoted to the Urdu language is asked by his

publisher friend to do an interview with Noor for his journal. What follows,

is in turn, comic and sad. Noor’s interview is botched by a novice sound

recordist. He dies suddenly, but Devan somehow manages to bring out a

collection of Noor’s poems.

Muhafiz is also about a highly expressive language that is being allowed to

die out in independent India for exclusively political reasons. All official

work in courts and police stations was done in Urdu before the partition of

India in 1947. Immediately after, Hindi became the official language of the

State. All avenues of Government employment suddenly closed for Urdu

students. Noor a poet of sensitivity and discernment became a victim of

capricious politics. To add insult to injury, his second wife sang his ghazals

and passed them off as her own.

Ismail chose the more difficult intimist mode for his film. Rarely did the

cinema go out of the poet’s house. There were precisely five other locations,

namely Devan’s home and his college; his colleague Siddiqui’s home and

the office of the Urdu weekly which has commissioned Devan to do Noor’s

interview and the visit by boat to Sufi Saints’ Mazar on an island in a lake.

The last scene of Noor’s funeral procession is seen mostly from a distance,

mainly to create scale.

Too many things went wrong for intention to match achievement. For one,

Ismail had been away from home for much too long; true he did come back

periodically to make films, but these were not connected closely with the

imperceptibly changing social scene. He did not really have the time to study

India for he was far too busy administering to the needs of the film at hand.

His knowledge of Urdu, for all his enthusiasm, was at best sketchy.

Choosing the poetry of a revolutionary poet like Faiz Ahmed Faiz to do duty

for most of Noor’s was a mistake. Anyone familiar with Faiz’s oeuvre will

immediately realize that it does not sit well on the lips of a bacchante like

Noor. Perhaps Josh Malihabadi’s poetry would have been more apt, for it

would have been closer to Noor’s spirit. More attention should have been

paid to his ghazals especially those picturised on his second wife. They are

sung in a lackluster manner by Kavita Krishnamurthy. Even the one

rendered by Hariharan lacks conviction. They should have had more

melody, more raga content. This was all the more surprising because Ustad

Zakir Husain was the composer.

Ismail was in much greater control doing his second film Cotton Mary

(2000) in English, with a script by Alexandra Viets adapted from her own

play. It was about an Anglo-Indian Ayah who decides to make herself

indispensable to her English mistress whose baby she helps to nurse. Mary,

though, a servant uses her dominant position over her employer suffering

from post-natal depression, to push her own case to go to England—home

country for the Eurasian. As expected all her schemes fall apart and she is

finally taken in by her relatives who she had till recently despised. Mary

never really comes to terms with her own identity.

This problem of identity forms the core of A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries

(1998) directed by James Ivory and based on an autobiographical novel by

Kaylie Jones, daughter of James Jones, author of From Here to Eternity, Go

to the Widow Maker and The Thin Red Line. The fundamental question of

recognizing oneself is raised once again in The Mystic Masseur (2002) the

last film that Merchant directed. V.S. Naipaul’s comic novel about an Indian

from Trinidad trying to discover himself in London allowed for a mixture of

wit and seriousness.

Ismail and James worked together for the last time together in 2003 on

L’Divorce, a farce set in contemporary Paris in which doltish Americans and

French do not know what to do with themselves. An American young

woman, pregnant with her first child, is abandoned by her upper class

French husband for another woman. The hapless mother-to-be is joined by

her younger sister newly arrived from the U.S. only to be seduced by her

estranged brother-in-law’s rake of an uncle! The absconding young husband

dies a gratuitous death; a sweet, chubby baby is born to his wife. Nobody

learns anything from what life has to offer.

Ismail Merchant’s life had a lot to offer. In middle age he had become a

gourmet and gourmand, a television celebrity and a writer of popular

cookbooks. He had proved his worth and durability as a producer of quality

cinema whose foundation lay in good writing and had gifted the world an

unusual and talented filmmaker in James Ivory. He had also paved the way

for those independent producers and directors, not necessarily from India,

who were to follow after him. Last but not least he had proved that if there

was a will to make a really fine film then the means to make it could also be

found. He was a man of rare qualities.