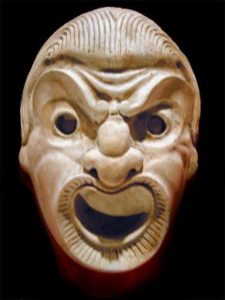

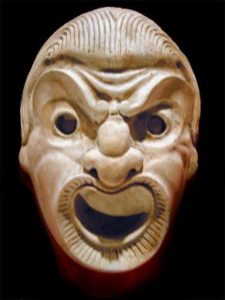

Purulia Chhau Mask Greek Theatre mask Saraikela Chhau Mask

Purulia Chhau Mask Greek Theatre mask Saraikela Chhau Mask

pics courtesy : 4to40.com / classicalwainui.wordpress.com

Theatre is a powerful means of communication; it essentially is a transformation that allows both the spectators and performers to come into contact with one another. The actors are thus able to play the role of another fictional persona. This is created with the aid of theatrical devices and objects. The mask is one such tool that helps the performer to alter his personality and thus recreate a totally new one. Most theatrical traditions of the East, in particularly, India, employ the powerful use of masks and they are essential to many ritual customs. Chhau, a major theatrical folk form of easternIndia namely Purulia (Bengal state) and Seraikela (Jharkhand) makes use of highly stylized masks to dramatize narratives. The antecedents of this masked folk form resound with ancient theatrical practices of the west. Chhau bears close semblance to the ancient Greek theatre and its origins may lie in the ancient tradition of Greece. My paper will closely examine these cross connections between Chhau and Greek theatre with special reference to the usage of masks.

Both Chhau and the Dionysiac religion were from the beginning inclined towards transformation. The individual persona in Chhau and Greek drama alters into a higher human being. According to Rajkumar Suvendra, an ace Chhau performer,

When I put on the mask I become impersonal. It is easier to slip into the body of another character. It passes its function to the body. Expression does not follow from my face to my body, but is transmitted from my body to my face. (53, Deo)

The best aid in both the theatrical forms would be hence costume and the masks. The generic words of both Chhau and tragedy in Greek drama give us important clues to this alteration of character. The Greek word tragos, from which tragedy is arrived also, means one who dresses up and performs. Tragedy is song in honor of the Greek gods. Komos the word from which comedy is arrived is where the members of the Greek drama when dressed up as animals take part in a happy parade. Thus this cult contains all the elements which are necessary for the development of a serious drama or gay comedy by disguised human beings.

Greek drama essentially developed as a mark to celebrate the god Dionysus. This fertility god is associated with both birth and death. He is the only god whose parents were not divine. He was twice born, his mother Semele died before he was born and his father Zeus removed him and deposited him in his thigh allowing the development of the offspring to emerge and develop later. Dithyramb (double birth) is a religious hymn that is sung and danced by a chorus to honor the god, a precursor to tragic drama.

Double-ness plays an important role here that emphasizes the imagery and myth. Dionysus was also the god of wine that elevated the followers into an ecstatic religious rapture. This gives them an exalted condition and the singing and dancing changed them into satyrs or sacrificial goat. They in the bliss is said to have direct effect and union with the gods. Humans therefore could become god like. Tragedy as mentioned before is also derived from the word tragoidia or goat song. The tragedy drama developed out of the Dithyramb which was a song of rejoicing and the chorus led the dance in honor of the Dionysus. This was originally performed by men in disguise of the demonic followers of god; they were the satyrs who had equine ears and tails as depicted in the vases. It was from this satyr the final form of drama developed.

The transformed individual thus required some façade or disguise. The significance thus of masking arises. The very act of wearing a mask and transformation into another character is a form of worship in itself. This double-ness, masked transformed individual in worship can be seen in the origin of Chhau. Scholars are divided in their opinion about the etymology of the word Chhau. Some researchers say that the word chhau is derived from the word Chhauni that means military camp. As this form involves the use of vigorous martial art techniques the form is said to have militaristic fervor. However one can also opine that the word Chhau is derived from the Sanskrit word Chhadma (Shadow) or hindi word Chhaya. This word clearly resounds to the mask or the disguise which is a sort of shadow that is created. In the eastern state of Assam masks are also called Chhon that bear a close resemblance to Chhau.

Both Chhau and the Greek theatre are closely related to ritual festivals. Greek theatre developed when the city of Dionysia celebrated the worshipping of the fertility God Dionysus. The city Dionysia lasted for about week not only celebrated the religious and the artistic achievements but display of wealth, power and public spirit. The tragedies were the center piece of the festival. They were performed on the fourth, fifth and sixth day of the festival week, each day devoted to a single playwright.

It is interesting to observe that Chhau is celebrated during the spring festival or the Chaitra parva in March- April. The festival lasts for about 13 days and Chhau is also the focal point of the festival. Chhau folk dance drama, similar to the Greek counterpart is not a part of the religious festivity but is purely for the entertainment of the people. This dance drama is also not performed everyday but is performed on the first, third and forth day.

While the rituals of the Chaitra Parva take place every year, the dances take place for a few days. 13 days of the rituals are performed by 13 people of different castes, who perform the customs daily. These people are called the bhagats who perform the ceremonies. Quite similar to the Greek festivals in which the people are transformed into satyrs the Bhagats also are transformed to gods during the festival. They gather around the Shiva temple and are given a sacred thread. By wearing that they hence become shiva gotra, belonging to the same caste as Shiva and they alter their caste and thus getting some socio-legal sanction to perform the rituals.

The bhaghats start the procession from the majna ghat or the bathing ghat with the accompaniment of music and dance. A flag staff is held by the man who is leading the festival called the Jarjar. They have a dip in the river and proceed to the temple and to the palace where the flag is kept all the time. On the first day they also visit the performance area to purify it. This ceremony is called the Akhada mada. The next day the jatra ghata takes place that is followed by the Chhau. The following evening is a ceremony called Brindabani in which god hanuman, the monkey god is prayed to. On the third night takes place the Garai bhar in which an episode relating to Krishna and the milkmaids is depicted. The god Krisna is depicted as stealing the clothes of the milkmaids who have gone to take a bath in the pond. A Chhau performance takes place in the evening. Chhau is not performed on the fifth night and it can be done only if a small fee is paid to the Shiva temple in the form of a fine.

The dances that take place are uniquely artistic and not ritualistic. There are no direct links between the festival and the dances and they provide entertainment for the people. The complex relationships developed among mythological narratives, social circumstances and theatrical displays are evident in the masked variants of Chhau. This grew out of tributes to Shakti or the primordial energy associated with exorcist practices developed during the Chaitra parva under different systems of patronage. Interestingly, Shakti like the god Dionysus is also worshipped widely as goddess of fertility in many parts of India.

In India many fertility festivals are often associated with wine and dance. During the spring time another major festival takes place in India called the Holi where by merry making, wine drinking and playing with colors is popular. Incidentally the God Shiva, who is worshipped in Chhau is also said to be fond of wine or Bhang, a heady drink made of milk, almonds and cannabis, which bears close resemblance to Dionysus the god of wine. During the Siva Ratri or the festival that honors the god Shiva many devotees indulge in drinking of Bhang.

Both Chhau and the Greek theatre have a participatory flavor. In Greece it was said to be the civic duty to perform in the festival, and nearly 500 citizens performed. Chhau too is based on cooperation amongst the people and it is also considered to be a public participation. The mask hence gives both Chhau and Greek theatre a corporate personality. It gives the actor the actor contact with god and removes him from everyday mundane existence.

Both chhau and Greek theatre developed under royal patronage. The wealthy Athenian citizens were obliged among their aristocratic duties to sponsor a play. This way they made their way to public education. The Athenian government officially sanctioned and gave support to a theatre festival for the best tragedy written. The government has made a record of these events. The dramatic festivals took place once a year and three writers were presented to for three continuous days. A separate day five comical writers were also presented.

Both in Seraikela and Purulia Chhau was fostered under royal patronage. In Seraikela the kings were not only patrons but are dancers as well, both Aditya Pratap Deo and princes Suvendra and Brojendra are quite famous and well known. Similar to the Greek theatre an annual competition is held between the various dancing groups. The maharaja or the king gives the annual prize. The whole town is divided into groups or akharas in which the dramatic form is developed. The town is divided into eight akharas the Bajar Sahi, Mera khodara Sahi, Brahman sahi, hunja sahi, kansari sahi, khodara sahi beribahu, uttar sahi and dakshin sahi. Chhau in Purulia is supported through households and there are also active competitions supported by rival political parties.

In Greece, famed actors were held in great honor and were even selected for diplomatic embassies. They were granted special privileges and received help and protection of sovereigns and leading personalities of the state. Aristodemus was invited to the court of Philip of Macedon and Thettalus to the court of Alexander the great, they were sent on important political missions. They belonged to certain guilds along with the stage managers, costumers, dancers and musicians. They produced epic, dramatic and lyrical plays old as well as new tragedies and comedies.

Chhau on the other hand is also organized into troupes that are under a leader or a guru. Instrumentalists, stage managers, directors and actors all form the essential part of the troupe. Chhau artists are given much social respect and honor. Many Chhau performances were taken abroad and Haren Ghosh, a troupe leader took Chhau toEurope as early as 1937-38.

Unlike Greek theatre there is no spoken word in Chhau and there are no dialogues. Conflicting emotions are concealed and they mainly focus on the mood or the theme of the drama. The whole body therefore has to give totality to expression and hence the actor liberates himself from the body through masks. By Angikabhinaya or expression through body the actor explores the dominant bhava or emotions.

Mask helps to express the bhava or the mood and the aesthetic sentiment or the rasa. This helps the shirobheda, the head movements and the girvabhed the neck movements, as it emits glances. Skill becomes the only determining factor as the age and the sex of the dancer is concealed through masks. It resounds to the lord of the world Shiva as the cosmic lord is Shiva and the whole universe is nothing but postures and postures and Shiva both sustains the life force as well as destroys it. Masks hence become the main aspect of this life force and it helps in the open acceptance of all and is in unison with nature and the universe.

Harmonies, movements and rhythms express the basic ideas of Chhau narratives. The basic movements are based on the parikhanda or the exercise of the shield and sword; they are a set of Chalis or movements that are performed from back to front in single duple and quadruple tempo. The movements are based on the daily activities and are therefore close to nature. For example gaits of animals are incorporated like bagh chali crane walk, goumutra chali the walk of a cow after passing urine and harin dain the jumping of deer. The activities of human beings, animals and birds are the inspiration behind the movements.

In Greek theatre it is said that Thespis or the first actor stepped away from the chorus and began to speak his own dialogue. He invented the first actor as he is said to have put a hypocrites, i.e. an answer and response giver, the opposite being exarchos. The leader and the chorus wore different costumes. Thepsis is said to have treated the face of his actors with white lead, then covered with cinnabar and rubbed it with wine lees and finally introduced masks of unpainted linen. Choerilus the successor of Thepsis made further experiments with masks and Phrynichus introduced the woman’s masks. Aeschylus introduced the second actor; dialogue thus could develop more freely and had greater dramatic significance. Aeschylus introduced new things to improve the fixed conventions in theatre. He introduced novelty in costume by giving the players sleeves, increased their height and introduced dignified masks. Greek tragedy was always a sacred ceremony in honor of the god and therefore the sacred robe, masks stayed as a symbol of god. In the later periods masks became larger and had more exaggerated features, but in the 5th century, as told by scholars, neither size nor shaper were overtly large and that the mask covered the entire head, included the appropriate hairstyle, beard, ornaments and other features as well.

Quite similar to Chhau, in the given structure of Greek theater, acting was close to dancing in which broad gestures and body posture and movements were very important. And of course the actors had to have excellent voices, with clear articulation and good breath control. Although much of the actor’s performance was spoken dialogue, he sometimes sung lyric solos. The mask served as a device to help make the actors voice be heard and it is said that something was constructed in the mouth of the mask so that the voice could be raised and heard. The mask made the actions more clear and the spectators would therefore be able to pay more attention to the actor’s movements rather then his appearances.

Both Chhau and Greek theatre’s performance space is outdoors. In Chhau, the acting area is circular and a wooden platform is erected to one side. The musicians sit on one side of the open area of about 20 feet. Performances take place in the night at about 10p.m. and goes on till sunrise. Drummers prelude the performances and display their talent. The show starts with the entry of the elephant god Ganesha and dramatic access of new characters. The audience yells intermittently and gives encouragement to the presentation. Initially lighting was with kerosene oil and now electrical lights are used for illumination. The mask thus provides the audiences with the much needed relief and help in the total involvement of the display.

In Greek theatres the performance took place outdoors in large amphitheatres. The city was well evolved and developed and nearly about 5000-20,000 people were participants. Therefore a large open space was needed for viewing, thus the amphitheatre developed by the end of the 5the century B.C. Audiences were seated in a semi circle and there were wooden bleachers for them to sit on. The enlarged and exaggerated expressions of the masks made it possible for the audiences to see the faces of the actors. The movements and gestures of the actors were very expressive and physical movements enabled the audiences to view them and these complementing the large masked face.

In Chhau each character is studied well and represented. Chhau masks can be divided into five categories, gods, goddesses, kings and queens, common men, demons and animals. The mask had both the facial portion and the head region. The demons had the extended eye, big lips, prominent chin shapely ears, moustaches, whiskers and eyebrows. They are painted in rich vibrant colors such as green, brown or deep purple. The gods are in softer pastel colors and the images are in the classical style so that they do not hurt the sentiment of the people. The head portion of the mask is highly decorated with golden and silvery paper, flowers, glass beads and nylon strings are used for hair.

Similarly masks of the Greek world were portrait masks as they depicted a particular character. The birds, frogs and the clouds the chorus represents the titles of the comedy masks. These masks had exaggerated features long beards, baldness or ugly noses. Comic masks less morphological elements and are asymmetrical features they also express strong emotion such as weeping, anger and acquiescence, agreement. Characters were easily identifiable and from every day life, they could be easily satire Socrates in Aristophanes Clouds and God Dionysus in the frogs they resembled the main characteristics and helped in creating a humorous ambience.

The masks covered the entire head and depicted hairstyle, facial features, beard and decorations. They were made up of perishable material and specific masks were created for each character. For instance, the chorus members in the tragedyl wore same masks so that one could clearly identify them as a group. The chorus in the Agamemnon was old men, too old to take part in the Trojan War. They would have hence been probably been bearded old and shriveled. The chorus would all thus appear to be similar, a notion widely held, if they all wore the same mask. The idea of having a group of individuals appear the same would be very hard unless masks were used.

The masks worn had the same effect as the costumes as they were personalized for each character. Special emotions were expressed on the mask, so the audience knew if a character was happy, upset, tired, or scared. Since the masks could be seen even in the last rows, the audience could hence tell how the character was feeling. For instance, Oedipus, or other royal figures, might have a higher forehead or crown on his head to signify his rank, whereas a comic slave might have large eyes and a huge mouth to show that he is observant and not unwilling to gossip. These physical characteristics of the mask made it easier to tell who was who onstage. The masks had to represent the outstanding features of the personality of the character.

Mask was a representation of the dramatist’s vision. Many Princes in Chhau wee also skilled mask makers and Rajkumar Aditya Pratap Deo personally supervised the making of masks. There are some special masks that represent two characters both in Chhau and Greek theatre. In Greek theatre it is believed that different masks were used for a powerful king who became blind. Helen was also represented in two different ways as she cut her hair and had a different spectacle. Each half of the mask represents a different expression and the performer performs laterally and suddenly turns showing the different face. Versatility of the actor was thus possible and it was easy for him to switch roles.

In Chhau the two faces of Shiva or the Ardhanariswara is represented in a unique way. It is shown in one mask itself and not by the usual division of the mask. The half male and female energy is shown by a three pronged mark on the forehead that shows the male energy and the lips curl into a small pout expressing affection. By thus tilting the mask one can get a different perspective and each half character is well studied and represented.

It is interesting to note that in both Chhau and Greek theatre women did not participate. Actor did not have specific characters but archetypes to represent them. The personality of the actors is hence lost and the main characteristic of the theatrical role is bought into prominence. The actor also has to perform many roles the mask helps him take up different personae and also in impersonating the female roles. The actor could be adaptable and change his personality and mood of the different characters that he was playing and his mask helps him make the transition into female parts.

In Greek theatre theatrical masks were constructed by linen cloth and then fortified by plaster by flour glue and fish glue and then it was painted. Male masks were more intense and female paler. They also covered the head with hair and the head was covered with a helmet and wool was attached to the head and then styled as hair. The mouth was left open in the tragedy masks and as the expressions showed more perturbation and passion and the opening became bigger.

The history of masks in India dates back t the Mesolithic periods. Excavations have revealed small hollow masks in the Indus Valley Civilization (2500 B.C. – 1200 B.C. At Chirand in Bihar, a northern state of India, a terracotta mask belonging to the fourth century was unearthed. The Natyasastra (8th century B.C.), a treatise on music and drama mentions masks or Partishirsa which seems to be very similar to the Greek counterparts. According to the text,

Different masks (pratshirsa) are to be used for men and gods according to their habitation, birth age…ashes or husks of paddy mixed with the paste of leaves of the bilva tree. This should be applied on the cloth. After the cloth dries one should pierce holes in it. These holes should be made after dividing the cloth into two equal halves.

Initial masks of Chhau were made of wood and earth that was heavy and made breathing very difficult. It passed down from cruder forms and became slowly sophisticated. Many techniques were introduced in the mask making process. The chhau mask is first made up of the clay that is found on the banks of the KharakeiRiver. The artist fixes the clay and lets it cool down to harden on a plank. This process is called the Mati gada or making of the clay. Then muslin gauze is pasted on it with two or three players giving it thick coating or paper, which is called kagaz chitano. The mask is then scrubbed off with the help of a sharp instrument called karni and it is polished. It is then painted in flat pastel colors the stylization being given on the eyebrows and mouth. This process is called Kabij lepa or painting. The flat pastel colors give it frankness, simplicity and boldness. The mask maker avoids realistic identification and the Mask of birds and animals such as deer (harin) or the prajapati (butterfly) is well stylized.

Mask making is a traditional occupation passed from father to son. The mask makers of Chhau live in Chorida village in Bengal and come from a set class and they bear the surname of Sutradhar or Das. The mask is made from February to June as it does not rain and in other seasons the artisans are engaged in carpentry and image making. Masks are rather frail they cannot stand the stress and strain of the performance. As it does not last for more than a year, it is always in high demand.

Masks therefore have been a part of the integral world of theatre rituals both in the eastern and western parts. The use and meaning behind the masks has evolved in many ways since the 5th century B.C. The dramatized rituals of India are very close in their resemblance to the ancient Greek ones. As correctly pointed out by Turner, rituals often use symbols such as objects, words relationships, events, gestures, or spatial units (19). Chhau is one such popular ritual folk drama of Eastern India (Mayurbhanj, Seraikela and Purulia) that uses such symbols i.e. elaborate and highly decorated masks. The masks used in the Chhau folk drama not only reveal crucial social and religious values that transform human attitude and behavior but also disclose influences of other ancient civilizations. Mask are thus a signifying object, it provided the much needed experience to both the actor and the spectators. Chhau masks hold our fascination and we can say that so much its history has its roots in ancient Greece that is evident in it.

This article was a paper that Gouri had read in a conference held at Waseda University in Japan, 2008 on Masks.