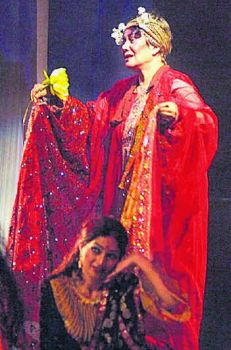

Still from Charandas Chor the Opening Play

National School of Drama, 6th Jan 2010

The National School of Drama is one of the foremost theatre training institutions in the world and the only one of its kind in India. Set up by Sangeet Natak Academy in 1959 as one of its constituent units, it became an independent entity in 1975 registered as an autonomous organization, fully financed by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India.

The school has two performing wings; Repertory and Theatre–in-Education. In 1999, the school organized its first National Theatre Festival, which was christened Bharat Rang Mahotsav, generally held during January each year. The festival, since it is hosted by a training institute such as the NSD, in fact works as training tool, by offering drama students an opportunity to view national and international performances, on one platform. Since there are very few functioning repertories in India and many productions do not enjoy long run, the festival is a rare opportunity to see so much together.

13th BRM

The 13th Bharat Rang Mahotsav, marks the beginning of the New Year with another milestone for the prestigious National School of Drama (NSD), as its annual national and international theatre festival opens with concurrent shows at multiple venues in Mandi House over two weeks from 7 to 22 January 2011. The BRM or Theatre Utsav, as it is popularly known, has come to be regarded as one of the largest and most important theatre festivals in Asia.

In keeping with the tradition of presenting outstanding theatre that allows for meaningful engagement, this year also the BRM will be presenting a rich fare of 81 productions selected out of nearly 450 proposals received from across India and from around the world. Taking forward the ‘Young Experimenters’ component of last year, BRM 13 also includes productions by graduates of the school in a synthesis of experience, new energy and vision.

Indian Component

The 13th BRM is inaugurated this year with an energetic and lively production of Habib Tanvir’s Charandas Chor from Assam directed by one of NSD’s alumni, Anup Hazarika.The works of eminent contemporary Indian playwrights like Girish Karnad’s Bikhre Bimband Dharamveer Bharati’s Suraj Ka Saatwan Ghoda are presented in striking new productions, alongside classics like Ibsen’s Lady of the Sea (Sagara Kanyaka) and Some Stage Directions for Henrik Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Alexander Pushkin’s Little Big Tragedies and Tagore’s ‘ A Wife’s Letter’ and ‘Bisarjan’. Shakespearean texts are re-explored in Macbeth and Othello (Reshmi Rumaal) while the human predicament in times of political turmoil is seen in Hamlet Machine, Samanadraba Mami, Gaddi Charan Di Kaahal Bari Si, Sharel Sha among others. Wishing to pay respects to Shyamanand Jalan, one of the most eminent of the 70’s generation of theatre director/actors who passed away recently, we have an evening devoted to him entitled Homage which showcases scenes from some of Jalan’s most outstanding productions produced by Padatik, Kolkata.

In dance/choreographed pieces like Grey is Also a Colour and Sweet Sorrow the focus is on inventing a movement based visual language. Zindagi Madhur hai Kumansenu mein, Quality Street, Khatijabai of Karmali Terrace and Salaam India revisit and reinterpret the received texts; While original scripts form the basis of Before The Germination..,Dreams of Taleem, Park, Mathemagician and Tritiyo Anko among others.From puppet plays to mime to dance/choreographed pieces to devised and experimental work in new media; the festival offers something for everyone.

International Dimension

This year the Festival will be hosting 23 productions drawn from 20 countries – China, Pakistan, Chile, France, UK, Bolivia, Chile, Japan, Egypt, Argentina, London, Germany, Sri Lanka, USA, Poland, Bangladesh, Nepal, Serbia, Ukraine, Italy and Norway.

At the forefront of the international section this year we have three theatre productions from France. The classic opera by Beaumarchais, Le Barbier de Seville, will be seen in a spectacular adaptation with a French director, Eric Vigner, directing a group of Albanian actors of the National Theatre of Tirana. Also from France is In Vivo, a dance piece, “Silent Words” a mime performance by Laurent Decol, as well as a photographic exhibition on the Footsbarn Theatre.

It is for the first time that there is such a large component from Latin America. We have the opportunity to see some contemporary works with Santa Maria de Iquique: Revenge of Ramon Ramon and a puppet performance Pueta Peralta (Chile), En un Sol Amarillo(Bolivia), Muare (Argentina). The foreign component like the overall festival is as eclectic as it is diverse. From China we have “The Amorous Lotus Pan” based on the original Sichuan opera of the same name. My Country, Life for Remembrance & The Quest (Egypt), Miranda (UK), He who Burns, Forest (USA), Surprised Body Project(Italy/Norway) are all fine examples of physical theatre. One can also find unique conceptualization in Ugetsu Monogatari (Japan) and All About Love (Ukrainian), while plays like Songs of Euripides, Brecht-The Hardcore Machine revisit received text. From the SAARC countries we have Khariko Ghera (Nepal), Khwabon Ke Musafir and Dara ( Pakistan), Makarakshaya-The Dragon (Sri Lanka), Aroj Charitammrito (Bangladesh) andStones and Mirrors (Afghanistan).

Festival in Chennai

In keeping with the practice started four years ago of sharing the fare invited for the festival at Delhi with another city, a part of the repertoire for BRM 13 will travel to Chennai with 19 of the invited productions for the Festival slated there from January 11 to 20, 2011. BRM Chennai will be presented at two venues Sir Mutha Venkatasubba Rao Concert Hall and Museum Theatre in the city.

Other Allied Events

The Festival, as a melting point of different cultures provides a unique opportunity for enjoyment of theatre as well as professional interaction. A series of synergetic wrap around programmes that have been organized around the Festival comprises ‘Meet the Director’ which includes talks & interactive sessions with some of the directors/designers on Performance Language/Scenography/Set & Light Design. Three Photographic exhibitions include Abhi-Vyakti, an exhibition celebrating the actor, working methodologies of Asian theatre schools (part of Asia-Pacific Bureau of Drama Schools meet); and an exhibition on the Footsbarn Company, France. There will be other programmes like, a special performance of dance and music by Min Tanaka & Aki Takahashi, French mime by Laurant Decol, solo performances based on African themes, four improvised performances on garbage called The Garbage Project and a performance on Social Gaming. The Asia PacificDrama Schools’ Workshop and Festival will also be a part of the allied events.

The Scale

The 81 performances and dozens of associated events in Delhi take place at seven venues – the Kamani Auditorium, the Shri Ram Centre, the LTG Theatre and the four venues within the premises of the NSD—Abhimanch, Sammukh, Bahumukh and Open Air besides its studio spaces like Abhikalp and TIE Space.

There are simultaneous performances and events spread over five to six venues each day during the two week run in Delhi and 18 productions at the two venues in Chennai during an eight day run there. BRM 13 will host around 3,000 theatre people from acrossIndia and the world. As in the past, the festival shows are expected to run to full houses, attracting nearly 70,000 spectators in Delhi and about 10,000 viewers in Bhopal.

To design, mount and coordinate a festival of this size in two cities involves a logistical feat that the NSD manages with élan because of its highly trained technical personnel, faculty and staff and the commitment they bring to the cause of theatre worldwide.

The mega event is an opportunity for the professionals, public and students alike to engage with the process and practice of contemporary theatre arts.