आजादी की दीवानी दुर्गा भाभी

समीक्षा — अनिल गोयल

भारतवर्ष को अंग्रेजों के चंगुल से छुड़ाने के लिये एक लम्बा संघर्ष चला था. इस में अठारहवीं-उन्नीसवीं शताब्दी में बंगाल में हुए सन्यासियों के विद्रोह से ले कर 1947 तक के सभी सशस्त्र और अन्य संघर्ष सम्मिलित हैं. लगभग पौने दो सौ वर्ष तक चले उस लम्बे संघर्ष की कुछ घटनाओं के बारे में कहानी, उपन्यास इत्यादि लिखे गये. लेकिन इन का अधिकतर इतिहास छिपा ही रह गया. सन 2022 में स्वतन्त्रता के पिचहत्तर वर्ष पूरे होने के अवसर पर, ऐसे अनजाने, भुला दिये गये समरांगण-वीरों के बारे में जानकारी को साधारण जन तक पहुँचाने के लिये अनगिनत कार्यक्रम आयोजित किये गये. ऐसे ही प्रयासों में से एक रहा लेखक-निर्देशक अक्षयवर नाथ श्रीवास्तव का लिखा और मंचित किया गया नाटक ‘आजादी की दीवानी दुर्गा भाभी’.

दुर्गा भाभी के नाम से हम में से कौन परिचित नहीं है? भगत सिंह और चन्द्रशेखर आजाद इत्यादि के साथी रहे भगवती चरण वोहरा की पत्नी थीं दुर्गा भाभी या दुर्गावती देवी. एक रोचक परन्तु सत्य तथ्य है, कि इतने सारे क्रान्तिकारियों में से केवल भगवती चरण वोहरा ही विवाहित थे… शेष लगभग सभी अविवाहित ही थे! इतने सारे पिस्तौल और बम चलाने वाले उग्र क्रान्तिकारियों के बीच यह एक महिला कैसे रहती होगी, और वह भी उन परिस्थितियों में, जहाँ इन लोगों के काम की गोपनीयता के चलते उन्हें अपने घर के आसपास के लोगों के साथ सम्बन्ध बनाने की सुविधा तो नहीं ही रही होगी, यह अपने में एक रोचक कल्पना ही है, जिस पर किसी लेखन ने कुछ नहीं लिखा है!

लेकिन दुर्गा भाभी के जीवन के इस पक्ष का रहस्य सम्भवतः उन की पारिवारिक पृष्ठभूमि में छिपा होगा! प्रयागराज (इलाहाबाद) के शहजादपुर गाँव में पण्डित बांकेबिहारी के यहाँ जन्मी दुर्गावती के पिता कलैक्ट्रेट में नजीर थे, और दादा थानेदार थे, अतः पुलिस और प्रशासन के प्रति साधारण जन के मन में रहने वाला भय दुर्गा के मन में नहीं रहा होगा.

इन सब क्रान्तिकारियों में से भगवती चरण सब से अधिक आयु के थे. सत्ताईस वर्ष की आयु में उन की मृत्यु हो गई थी. दुर्गावती उस समय पर कुल बाईस वर्ष की अवस्था की थीं. इतनी कम आयु में विधवा हो गई दुर्गा भाभी ने अपना बाकी का जीवन भी स्वतन्त्रता के संघर्ष में भाग लेते हुए ही गुजारा. लेकिन वह जीवन कैसा रहा होगा, जिस में न सिर्फ उन के अपने पति, बल्कि एक-एक कर के उन के लगभग सभी प्रमुख साथी भी मारे गये थे? भगत सिंह, सुखदेव और राजगुरु को फाँसी हुई, चन्द्रशेखर अंग्रेजों से लड़ते हुए मारे गये, और भी सभी साथी या तो मारे गये, या फिर जेलों में गये या फिर भूमिगत हो कर रहते रहे. और यही नहीं, एक एकाकी जीवन जीने को मजबूर हुई दुर्गा भाभी और उन के बच रहे कुछ साथियों में से अधिकतर को स्वतन्त्रता-प्राप्ति के बाद भी कोई सम्मान या पहचान भारत की सरकार ने नहीं दिया. ऐसे विकट जीवट वाली दुर्गा भाभी अकेली ही रहती रहीं, और दिल्ली के निकट गाजियाबाद में एक स्कूल चलाती रहीं, जहाँ अक्टूबर १९९९ में उन की मृत्यु हुई.

ऐसी साहसी महिला के जीवन पर नाटक लिख कर उसे मंचित करने का अनुकरणीय काम किया अक्षयवर नाथ श्रीवास्तव ने. जून २०२३ को इस नाटक का प्रदर्शन राष्ट्रीय नाट्य विद्यालय के अभिमंच में देखने को मिला.

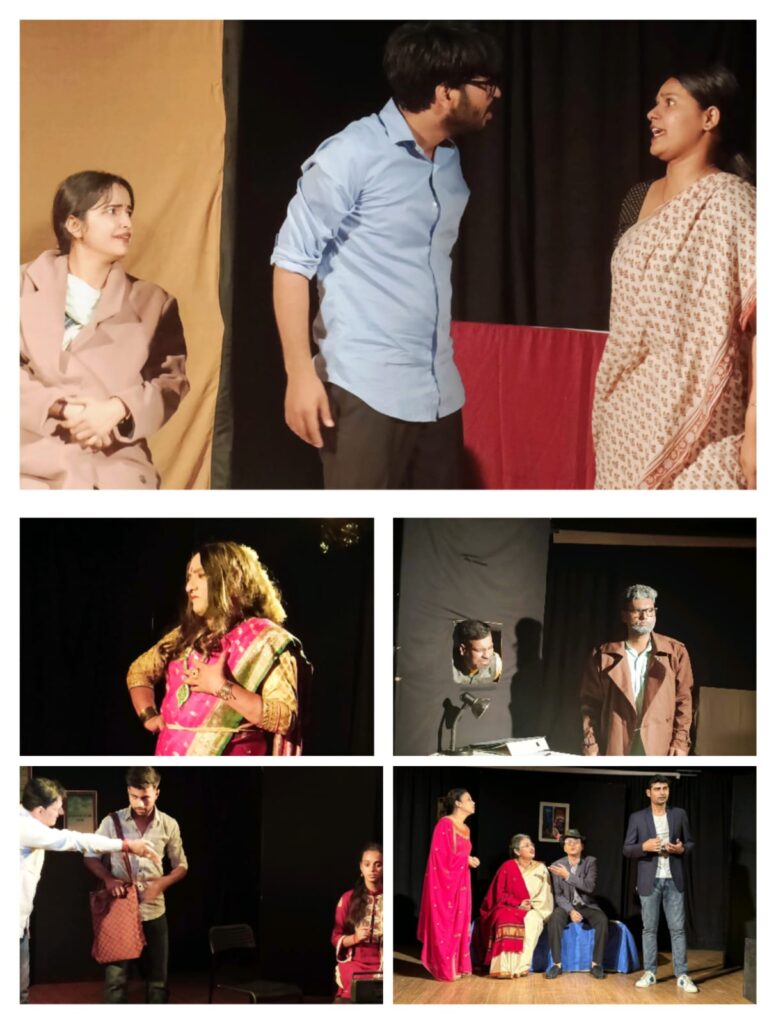

दुर्गावती के रूप में तनु पाल और भगतसिंह की भूमिका में शिवम सिंघल ने अपने अभिनय से बहुत अधिक प्रभावित किया. चन्द्रशेखर आजाद की भूमिका में आभास सिंह तथा अन्य भी सभी कलाकारों ने अपने दक्ष अभिनय से प्रभावित किया. लेकिन मुझे लगता है कि पुलिस इंस्पैक्टर और सी.आई.डी. इंस्पैक्टर के चरित्रों को इतना हास्यास्पद बना देने से नाटक की गम्भीरता प्रभावित हुई. ब्रिटिश राज की भारतीय पुलिस के नृशंस कृत्यों को कौन नहीं जानता… किस प्रकार से अपने अत्याचारों से उन्होंने क्रान्तिकारियों को परेशान किया था, यह हम सब को पता है. उन चरित्रों को मजाहिया बना देने से दर्शकों के मन पर होने वाला उन अत्याचारों का अनुभव कमजोर पड़ जाता है.

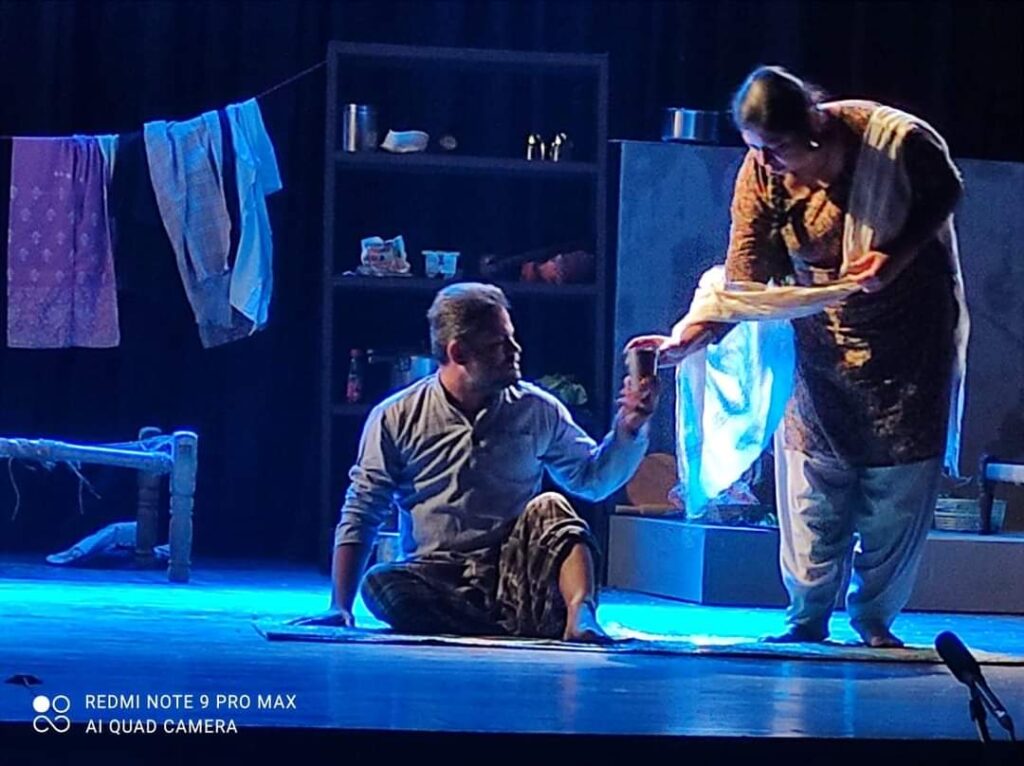

मंच परिकल्पना में भी कुछ परिवर्तन की आवश्यकता अनुभव होती है. मंच के बाएँ हाथ पर बनाये गये विशालकाय रेलवे स्टेशन का कोई विशेष प्रयोग नहीं हुआ, जब कि उस ने पूरे समय मंच के बड़े हिस्से को घेरे रखा. और जो पूरे नाटक में गतिविधियों का प्रमुख केन्द्र था, भगवतीचरण वोहरा का घर, जिसे बाद में कलकत्ता के घर और अन्य स्थानों के रूप में भी प्रयोग किया गया, वह दबा-दबा सा रहा, जिससे पूरा प्ले-एरिया या अभिनय के लिये उपलब्ध स्थान एक कोने में सीमित हो कर रह गया. मंच पर गतिविधियों के विभिन्न स्थलों के बीच एक अनुपात बनाना पड़ता है, जिस का ध्यान न रखने के कारण यह नाटक उभर कर आ ही नहीं पाया. ऐसी ही समस्या प्रकाश-संयोजन के साथ भी रही, जिस में मंच का प्रकाश लगातार दर्शकों की आँखों पर पड़ कर दृश्यों की दृश्यव्यता को प्रभावित करता रहा. एल.ई.डी. पर्दे के आगे रखी एक लाईट तो पूरे नाटक में दर्शकों की आँखों में चुभती रही. आज के समय में मंच-आलोकन डिजाइनर का क्रीड़ा-स्थल अधिक बन गया है, नाटक के कथानक को दर्शकों तक पहुँचाने में सहायक होने का साधन कम रह गया है. नाटक की दर्शकों तक सम्प्रेषणीयता में बाधक बन रही इस प्रवृत्ति पर गम्भीरता से विचार करना होगा.

हरी सिंह खोलिया रूप-सज्जा के माहिर माने जाते हैं, और इस नाटक में की गई रूप-सज्जा से उन्होंने अपनी सिद्ध-हस्तता को एक बार फिर से स्थापित कर दिया. वस्त्र-विन्यास भी नाटक के अनुरूप ही था. एल.ई.डी. पर्दे का प्रयोग कर के इतने सारे स्थलों को मंच पर बनाने की समस्या का निर्देशक ने कुशलता से हल पा लिया. लगभग अठावन विभिन्न भूमिकाओं वाले इस नाटक में, इतनी अधिक संख्या में कलाकारों के मंच पर आने-जाने इत्यादि सभी चीजों को सम्भालना आसान नहीं होता. इस के लिये मंच-प्रबन्धन के लिये जिम्मेवार व्यक्ति की प्रशंसा करनी होगी, कि नाटक में कहीं कोई विशेष दर्शनीय चूक नजर नहीं आई! मंच पर दो कारों को ला कर घटना को जीवन्त बना देने के लिये अक्षयवर जी की प्रशंसा करनी होगी!

इतनी सारी घटनाओं को दो-ढाई घंटे के नाटक में समेटना आसान नहीं होता. फिर भी, नाटक के आलेख में कुछ चुस्ती लाने की आवश्यकता से इंकार नहीं किया जा सकता. अभी स्वतन्त्रता के संग्राम में अपने जीवन को होम देने वाले हजारों किस्से दबे पड़े हैं. आशा है कि इस नाटक को देख कर अन्य लोग भी अपने जीवन की आहुति देने वाले उन व्यक्तियों के बारे में नाटक बना कर इस यज्ञ में अपना योगदान देंगे.