✨ Antaryatra – When Art Becomes a Journey Within

An evocative evening of imagination, meditation, and Indian aesthetics at Kala Sankul

New Delhi, July 27

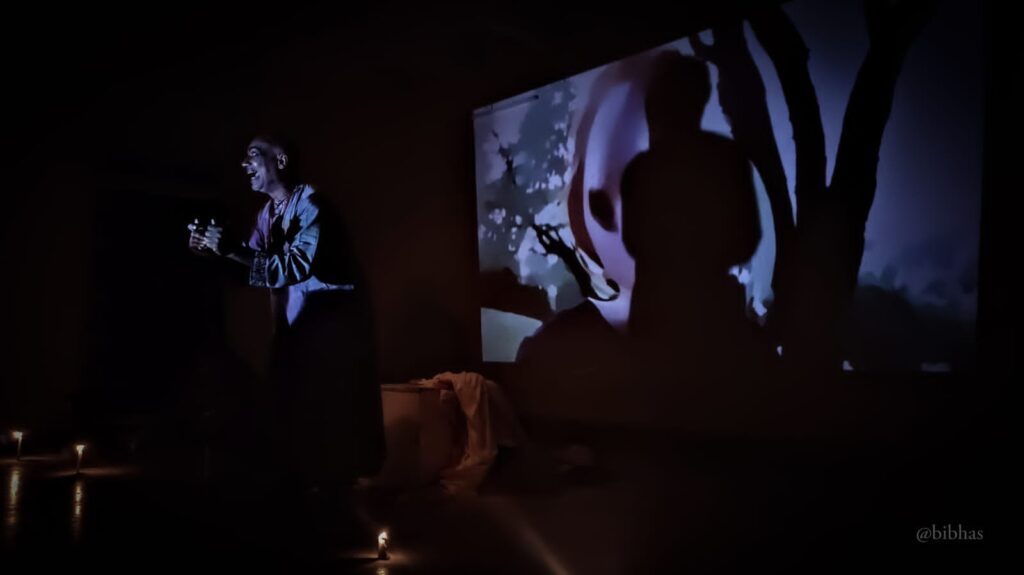

There are evenings that entertain, and then there are evenings that elevate. The recent Monthly Art Symposium hosted at Sanskar Bharati’s central office, Kala Sankul, was undoubtedly the latter. With the theme “Antaryatra: Imagination, Art and Meditation,” the gathering blossomed into an intimate and deeply reflective cultural experience — one that resonated with the soul.

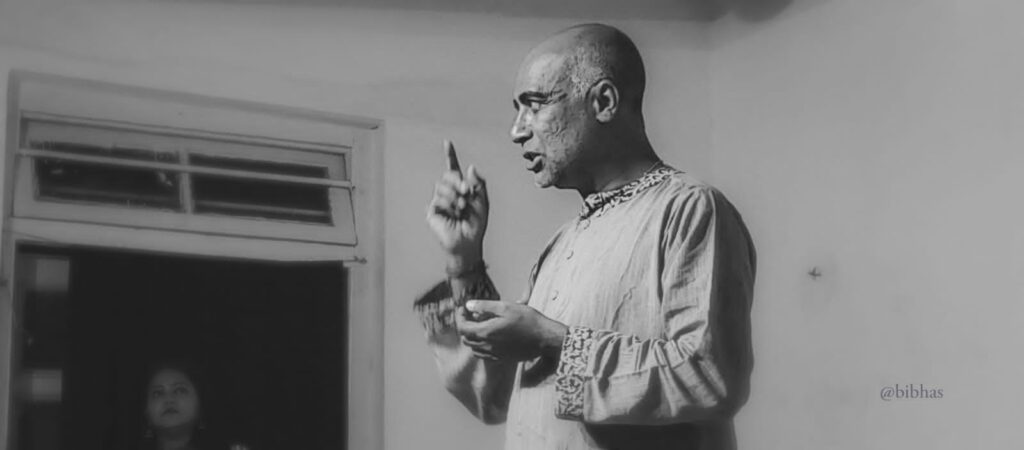

Anchoring this vibrant dialogue was Smt. Vaishali Gahlyan, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Miranda House, University of Delhi. In a keynote address that seamlessly wove aesthetics with spirituality, Dr. Gahlyan explored the essence of Indian art as a form of inner sadhana (spiritual practice), stating:

“Indian art is not merely a display of beauty, but a meditative discipline — a trinity of imagination, creation, and contemplation that draws the artist closer to self-realization.”

Her thoughts echoed through the hall, reaffirming the ancient Indian perspective of art not just as expression, but as realization — a means to connect the microcosm with the macrocosm.

The event commenced with a traditional lamp-lighting ceremony, presided over by Smt . Vaishali Gahlyan along with symposium convenor Smt. Shruti Sinha, co-convenor Sh. Vishwadeep, Delhi Prant’s stage art convenor Sh. Raj Upadhyay, and programme director Sh. Shyam Kumar — each a dedicated torchbearer of India’s living art traditions.

🎶 Monsoon Melodies & Cultural Echoes

As the gentle drizzle of Sawan graced the capital, the atmosphere inside Kala Sankul mirrored the rhythm of the rains. A soulful Kajri recital swept through the venue, filling hearts with seasonal nostalgia. Led by Sneha Mukherjee, along with young vocalists Lavanya Sinha, Manya Narang, and Ruhi, the performance paid homage to the folk spirit, evoking memories of lush fields and festive homes.

Amit Sridhar’s deft touch on the synthesizer and Tushar Goyal’s crisp tabla beats added texture and depth, making the musical interlude a celebration of India’s rich rural music heritage.

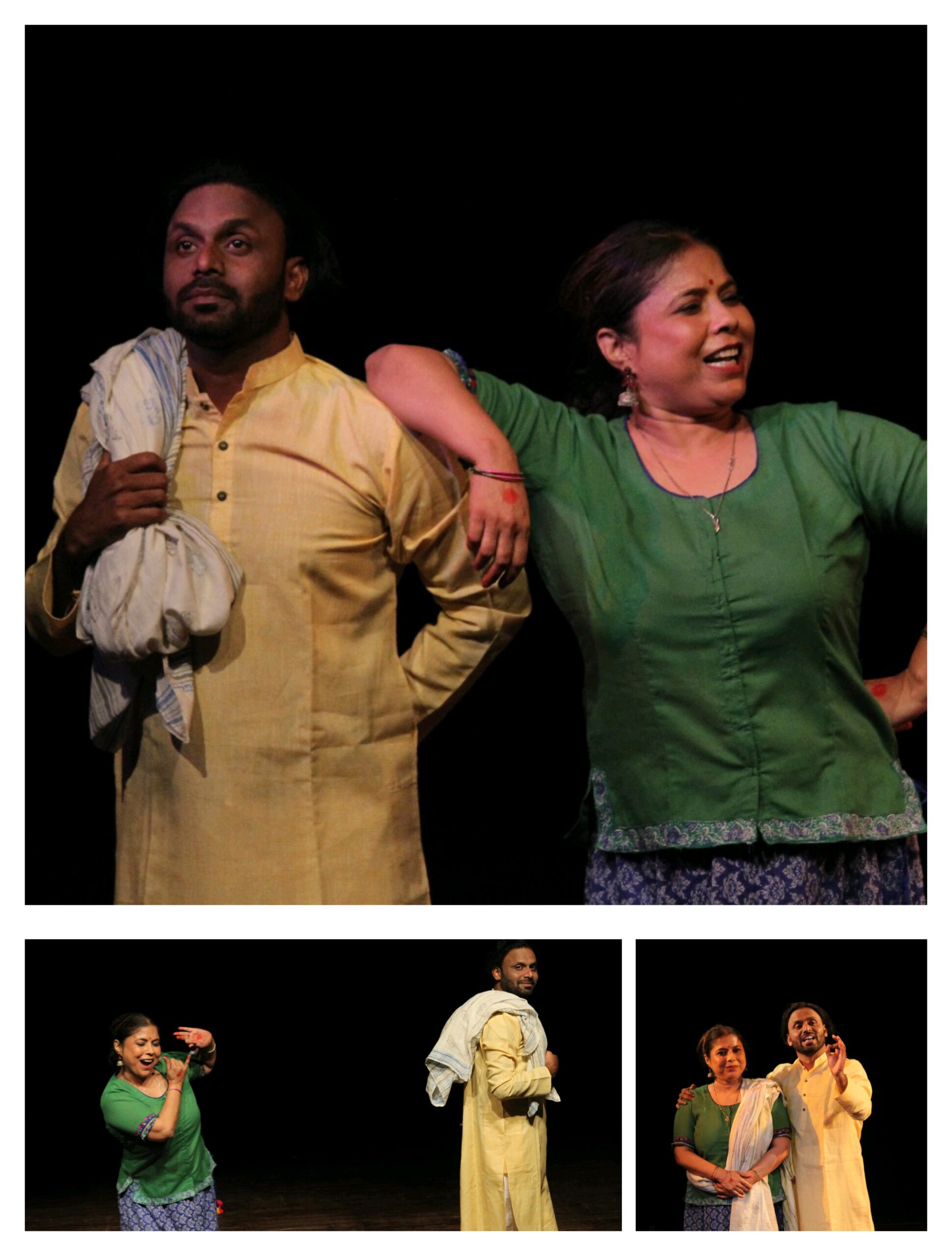

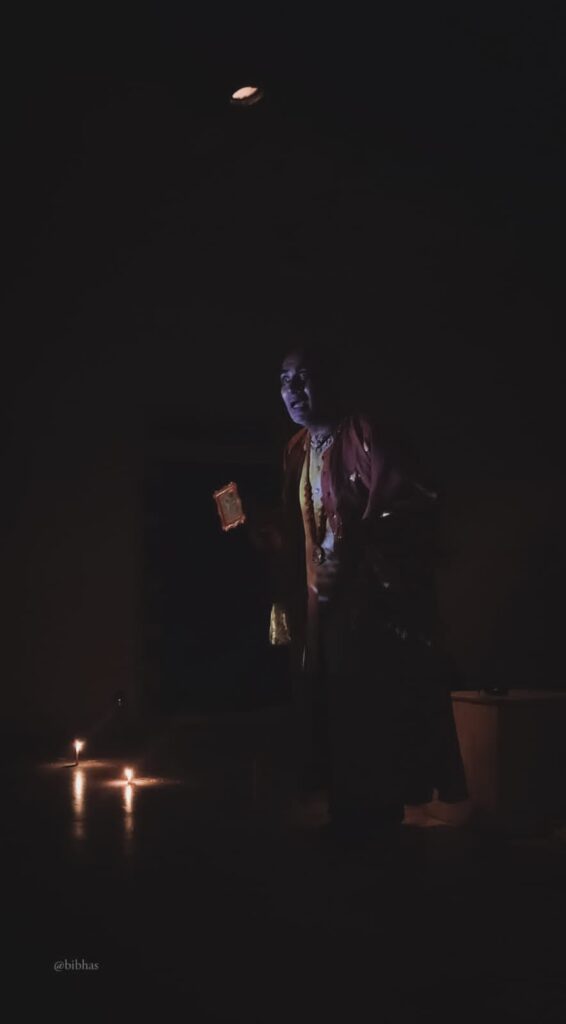

👣 Dance as Devotion

What followed was nothing short of poetry in motion. Kathak dancer Neelakshi Khandekar Saxena transported the audience with a presentation that captured the grace, strength, and rhythmic prowess of Indian womanhood. Her recital was a vivid tapestry of bhava, laya, and gati — a visual meditation that perfectly embodied the evening’s theme of “Antaryatra.”

🌟 Presence of Stalwarts & Artistic Solidarity

The event drew an impressive gathering of eminent personalities from Delhi’s cultural milieu. Among those in attendance were Kathak legend Pandit Rajendra Gangani, noted flautist Pandit Chetan Joshi, and National School of Drama Registrar Shri Pradeep Mohanty. Their presence lent gravity and warmth to the event, as did the attendance of various scholars, researchers, young artists, and art lovers.

Adding to the smooth flow of the evening was the poised anchoring by Sh. Kuldeep Sharma, whose narration stitched the various segments with thoughtfulness and flair.

🙏 Behind Every Great Evening…

Behind the artistic grace of the evening lay the quiet dedication of many. Pradeep Pathak (tabla), Shraboni Saha, Garima Rani, Harshit Goyal, Saurabh Tripathi, Brijesh, Shivam, Vijendra, Mrityunjay, Sushank, Sakshi Sharma, Priyanka, and Kala Sankul’s devoted manager Shri Digvijay ji — each played a vital role in ensuring a seamless, dignified, and heartfelt celebration of Indian arts.

🌸 A Living Space for Thought & Tradition

With each passing month, Sanskar Bharati’s Monthly Art Symposiums are evolving into a sacred space for dialogue, tradition, and creative introspection. More than a platform for performances, they are becoming vibrant forums where Indian art finds contemporary voice, where aesthetic experience meets spiritual insight, and where the soul of Bharat breathes freely in brushstrokes, rhythms, and reflections.