20 जनवरी होगा बिफ़्फ़ का धमाकेदार आयोजन। धरती पर चमकेंगे फ़िल्मी सितारे।

लेख: डॉ तबस्सुम जहां

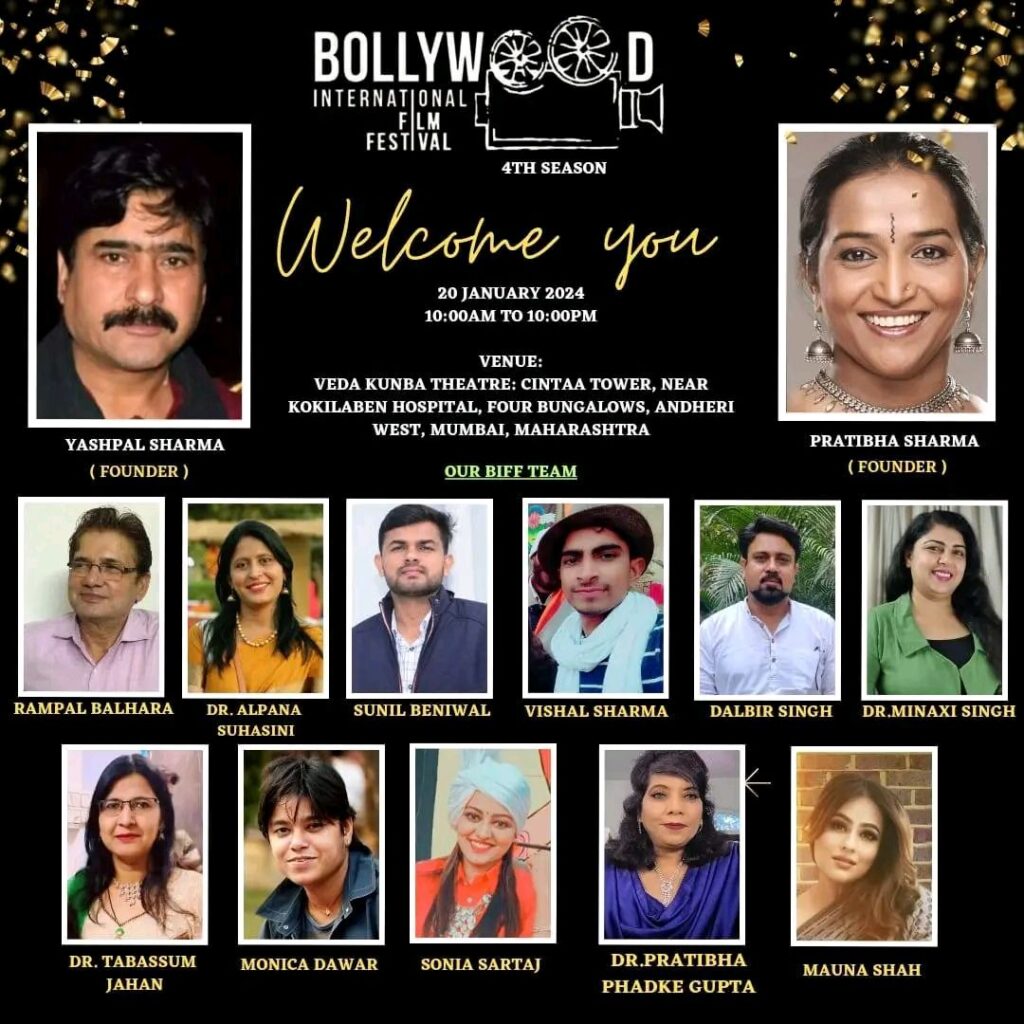

बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल का चौथा आयोजन मुंबई में होने जा रहा है। हर साल की तरह इस बार भी सिनेमा जगत की अनेक बड़ी हस्तियाँ इसमें शिरक़त करेंगी। यह कार्यक्रम इस बार भी मुंबई में 20 जनवरी 2024 को वेदा कुनबा थियेटर, अँधेरी वेस्ट में होने जा रहा है। बॉलीवुड एक्टर डायरेक्टर प्रतिभा शर्मा तथा सुप्रसिद्ध एक्टर डायरेक्टर यशपाल शर्मा बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल के संस्थापक व आइकॉन फेस हैं।

बता दें कि बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल की स्थापना प्रथम लॉकडाउन से पहले 2020 में हुई थी। तब से इसके लगातार तीन कामयाब सेशन हो चुके हैं। 2020-2021दो सालों से अनवरत ऑनलाइन होने वाले इस फेस्टिवल का ऑफलाइन संचालन तीसरी बार पिछले बरस 17-18 दिसंबर को मुंबई के ओशिवारा हारमनी मॉल अंधेरी में हुआ था। इसका चौथा एक दिवसीय सेशन इस बार भी 20 जनवरी 2024 को वेदा कुनबा थियेटर, अँधेरी वेस्ट मुंबई में होने जा रहा है।

बिफ़्फ़ अपने तीन बरस की कामयाब यात्रा कर चुका है। वर्तमान समय के कमर्शियल दौर में बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फिल्म फेस्टिवल का एक ही उद्देश्य है कि दर्शकों तक ज़्यादा से ज़्यादा स्तरीय व बेहतरीन फ़िल्मे पहुँचाएं। फ़िल्म जगत से जुड़े नए लोग फ़िल्म जगत से जुडी बारिकियों को समझें, सीखे और इसका लाभ उठाते हुए कम संसाधनों के साथ भी अच्छी फ़िल्म निर्माण कर सके। बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल उन लोगों के लिए काम करता है जिनके पास प्रतिभा तो हैं परंतु मंच और अच्छे मार्गदर्शन का अभाव है। यह मंच नई प्रतिभाओं को आगे लाता है। फेस्टिवल मे होने वाली मास्टर क्लास से इन नई प्रतिभाओं को मार्गदर्शन मिलता है। बिफ़्फ़ मुंबई मे फ़िल्म जगत से सम्बंधित लोग अपनी फीचर फ़िल्म, शॉर्ट फ़िल्म, डॉक्यूमेंट्री, मोबाइल फ़िल्म, स्टूडेंट्स फ़िल्म, एनीमेशन फ़िल्म और म्युज़िक वीडियो इसके अलावा सिनेमा पर आधारित पुस्तके भी भेज सकते हैं। चयनित बेहतरीन फ़िल्म को वर्ष के अंत में होने वाले फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल में दिखाया जाता है। बेहतरीन कैटेगरी को अवार्ड भी दिया जाता है।

बिफ़्फ़ मुंबई मंच की सशक्त हस्ताक्षर हिंदी सिनेमा तथा रंगमंच के बेहतरीन और लाजवाब एक्टर यशपाल शर्मा और उनकी पत्नी प्रतिभा शर्मा किसी परिचय के मोहताज नहीं हैं। लगान फ़िल्म में अपने ज़बरदस्त अभिनय का लोहा मनवाने वाले यशपाल शर्मा ने फ़िल्म यहाँ, अनवर, गुनाह, दम, वेलकम टू सज्जनपुर, गैंग्स ऑफ वासेपुर 2, गंगाजल, राउडी राठौड़, सिंह इज़ किंग सरीखी फिल्मों में अपने अभिनय का बेहतर प्रदर्शन किया वहीं दादा लख्मीचंद जैसी क्लासिकल संगीतमय फ़िल्म बना कर डायरेक्शन के क्षेत्र में भी बुलन्दी के सभी झंडे गाड़ दिए। वहीं दूसरी ओर प्रतिभा शर्मा एक्टर डायरेक्टर होने के साथ यह एक समाज सेविका के रूप में भी जानी जाती हैं जिनका ‘पहल फाउंडेशन’ आर्थिक संकट में फंसे कलाकारों की सहायता करता है। इनकी रचनाधर्मिता की बात करें तो इनकी तक़रीबन सभी छोटी बड़ी फिल्में, डॉक्यूमेंट्री तथा कविताएं व कहानी स्त्री जागरूकता व स्त्री सशक्तिकरण की बुलन्द आवाज़ हैं।

यशपाल शर्मा तथा प्रतिभा शर्मा ने बताया कि आज के कमर्शियल दौर में बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फिल्म फेस्टिवल का एक ही उद्देश्य है कि दर्शकों तक ज़्यादा से ज़्यादा स्तरीय व बेहतरीन फ़िल्मे पहुँचाएं। फ़िल्म जगत से जुड़े नए लोग फ़िल्म जगत से जुडी बारिकियों को समझें, सीखे और इसका लाभ उठाते हुए कम संसाधनों के साथ भी अच्छी फ़िल्म निर्माण कर सके। बिफ़्फ़ की शुरु होने के बारे में प्रतिभा शर्मा बताती हैं कि यह फेस्टिवल बातों-बातों में शुरु हुआ था और जैसे ही बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल नाम दिमाग में आया तो इसे आनन फानन तुरंत ही रजिस्टर्ड कर लिया गया। हालांकि इसे लाने के पीछे हमारा एकमात्र उद्देश्य अच्छे सिनेमा को प्रमोट करना है। यशपाल शर्मा इसके मक़सद और उद्देश्य के संबंध में बताते हैं कि जो लोग अच्छे टैलेंटिड हैं, अच्छे कलाकार हैं अच्छे डायरेक्टर व एक्टर हैं वो लोग कई बार फेस्टिवल को लेकर इनसिक्योर महसूस करते हैं कि पता नहीं इतनी बड़ी-बड़ी फिल्में फेस्टिवल में आएंगी तो पता नहीं उनका नम्बर आएगा या नहीं। पर मैं उनको भरोसा दिलाता हूँ कि अगर उनकी फ़िल्म में दम है या उनकी एक्टिंग में दम है तो बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल उनको ज़रूर सिलेक्ट करेगा और उनको सम्मानित करेगा व उनको अवार्ड देगा।

बॉलीवुड इंटरनेशनल फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल उन लोगों के लिए काम करता है जिनके पास प्रतिभा तो हैं परंतु मंच और अच्छे मार्गदर्शन का अभाव है। यह मंच नई प्रतिभाओं को आगे लाता है। फेस्टिवल मे होने वाली मास्टर क्लास से इन नई प्रतिभाओं को मार्गदर्शन मिलता है।

वर्तमान में देश विदेश में अनेक छोटे बड़े फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल हो रहे हैं अन्य फेस्टिवल से इतर बिफ़्फ़ कैसे ख़ास है या बिफ़्फ़ ने कैसे अपनी छवि बाक़ी फेस्टिवल से अलग बनाई है इस संबंध में प्रतिभा शर्मा कहती हैं कि उनकी जो ज्यूरी है वह बहुत स्पेशल है। नेशनल और इंटरनेशनल अवार्ड विनिंग ज्यूरी है। उनके शब्दों में “हम निष्पक्ष होकर सारा फैसला देते हैं। पहले हम लोग जो होम ज्यूरी हैं वो देखती हैं वो इस तरह फाईनल फैसला लेते हैं उसके बाद चयन होता है फिल्मों का। इस तरह बहुत ही ट्रांसपेरेंसी होती है। इसमे हम किसी की फ़िल्म अच्छी हो तभी अवार्ड देते हैं।” यशपाल शर्मा के अनुसार “आजकल बहुत सारे फेस्टिवल हो रहे हैं लेकिन मैंने जितने भी फेस्टिवल देखें हैं 90% फेस्टिवल उनकी मैनेजमेंट में गड़बड़ी, उनका एक अच्छा सिनेमा दिखाने में गड़बड़ी, उनका अपने दोस्तों का सिनेमा दिखाने की गड़बड़ी यानी वह केवल अपने कुछ लोगों का सिनेमा दिखाते हैं जिन्हें वह प्रमोट करना चाहते हैं। जब कोई फ़िल्म चल रही है किसी फेस्टिवल के अंदर और वह लोगों को बोरिंग लगे अच्छी न लगे, उसका मानक सही न हो यानी उसकी डिग्निटी सही न हो, फ़िल्म की क्वालिटी अच्छी न हो तो असल में हम अपने दर्शकों को तोड़ रहे होते हैं और उनको जोड़ नहीं रहे होते हैं। केवल कुछ लोगों को खुश करने के लिए दिखा रहे होते हैं।” उनके अनुसार उनके बिफ्फ में ऐसा बिल्कुल नहीं होगा। वे बताते हैं कि पिछले सेशन में बहुत लोग हमारे खिलाफ़ हो गए थे कि हमारी फ़िल्म क्यों नहीं दिखाई। वह फिल्में ज्यूरी ने सिलेक्ट नहीं की थीं इसलिए नहीं दिखाई। हमें इस बात का कोई ग़म नहीं है हम अपनी क्वालिटी के तौर पर अपना फेस्टिवल आगे बढ़ाते रहेंगे और आगे चलते रहेंगे।

बिफ़्फ़ मुंबई का पिछला तीसरा आयोजन मुंबई में हुआ जो अपने आप में बेहद सफल रहा। महीनों तक देश विदेश में इस फेस्टिवल की चर्चा होती रही। खासतौर पर यह फेस्टिवल दो दिन दिखाई जाने वाली सामाजिक फिल्मों को लेकर अधिक चर्चा में रहा। प्रतिभा शर्मा बताती हैं कि बिफ़्फ़ अपने सामाजिक दायित्वों को पूरी तरह से निभा रहा है। वार्षिक फेस्टिवल के अलावा हम लेट्स टॉक के मंच पर सिनेमा जगत से जुड़े कलाकारों व सेलिब्रिटी को बुलाकर विविध विषयों पर चर्चा की जाती है । सिर्फ़ एक्टिंग ही नहीं या सिर्फ़ निर्देशन ही नहीं या फ़िर संगीत ही नहीं बल्कि फ़िल्म से जुड़े सभी पहलुओं पर। तो एक सर्वांगीण चर्चा जो इस मंच पर होती है और मेरे ख़्याल से जिस मंच पर सर्वांगीण चर्चा होती है वो स्वयं अपने आप मे एक सामाजिक दायित्व निभा रहा है। उनके कथानुसार “बिफ़्फ़ अपना सामाजिक दायित्व निभा रहा है या नहीं यह तो दर्शक तय करेंगे और दर्शकों का, लोगों का अभी तक हमें बहुत प्यार मिला है तो मेरे ख़्याल से हम लोग सही जा रहे हैं।” यशपाल शर्मा का भी मानना है कि उनके बिफ़्फ़ में इंडियन फिल्में और विदेशी फिल्में दोनों शामिल हैं चाहे वह शॉर्ट फ़िल्म हों चाहे फ़ीचर फ़िल्म हों, चाहे डॉक्यूमेंट्रीज़ हों या वेबसीरीज़ हों या बाक़ी हों तो इसलिए इसमें जो विदेशी अच्छा सिनेमा है वो हम को देखने को मिलता है। और जो हमारा अच्छा सिनेमा है वो विदेशियों को देखने को मिलता हैं। पिछले फेस्टिवल में मुझे अभी तक याद है कितनी सारी विदेशी फिल्में आई थीं जिनको देखना अपने आप में कमाल का अनुभव था। हमको एक अच्छा दर्शक भी होना है क्योंकि सिनेमा देख कर हम बहुत कुछ सीखते हैं। तो हमारे फेस्टिवल में एक मेला जैसा लगा है तीन साल। और बक़ायदा लोगों ने ख़ूब देखा है सिनेमा और तारीफ़ भी की है। सैंकड़ों मैसेज भी आए हैं। यह बहुत बड़ी उपलब्धि है हमारा यही मक़सद है कि विदेशी सिनेमा भारतीयों तक पहुँचे और भारतीय सिनेमा विदेशियों तक पहुँचे बिफ़्फ़ ने दोनों जगह आशातीत सफलता पाई है।

प्रतिभा शर्मा और यशपाल शर्मा बताते हैं कि बिफ़्फ़ में लोग फीचर फ़िल्म, शॉर्ट फ़िल्म, डॉक्यूमेंट्री, मोबाइल फ़िल्म, स्टूडेंट्स फ़िल्म, एनीमेशन फ़िल्म और म्युज़िक वीडियो इसके अलावा सिनेमा पर आधारित पुस्तक भी भेज सकते हैं। चयनित बेहतरीन फ़िल्म को जनवरी में होने वाले फ़िल्म फेस्टिवल में दिखाया जाएगा। इतना ही नहीं बेहतरीन कैटेगरी को अवार्ड भी दिया जाएगा।

बिफ़्फ़ फेस्टिवल सीज़न 4 जनवरी में मुंबई में होगा उसके लिए ज़ोरो शोरो से तैयारियां हो रही हैं एक ख़ास बात जो बिफ़्फ़ को अन्य फेस्टिवल से अलग करती है वो इसकी रचनाधर्मिता के प्रति लगाव है यही कारण है कि इस बार पहली बार लोगों की सिनेमा जगत विषय पर लिखने वाले लेखकों को भी फेस्टिवल में शामिल किया गया है प्रतिभा शर्मा और यशपाल शर्मा चूंकि स्वयं लेखन और साहित्य जगत में रूचि रखते हैं इसलिए फेस्टिवल में उन पुस्तकों को भी शामिल किया गया है जो सिनेमा से जुड़ी हैं। चयनित पुस्तकों को भी अवार्ड दिया जाएगा।

पुस्तक ‘दूसरी हिंदी’ मे कविताएं संकलित। इनकी प्रथम लघुकथा चौथी दुनिया समाचार पत्र में छपी। इसके बाद समय-समय पर अनेक कहानियां, लघुकथाएं, कविताएँ, पुस्तक समीक्षा, फ़िल्म समीक्षा, आलेख, आलोचनात्मक समीक्षा देश-विदेश की विभिन्न प्रतिष्ठित पत्र-पत्रिकाओं जैसे सदभावना दर्पण, संवदिया, पुरवाई (ब्रिटेन), हम हिंदुस्तानी (अमेरिका), साहित्यकुंज (कनाडा), नेशनल एक्सप्रेस, विभोम स्वर, सामायिक सरस्वती, विश्वगाथा, आगमन, अनुस्वार, पैरोकार, आधुनिक साहित्य पत्रिका, हस्ताक्षर, जामिया हिंदी विभाग की पत्रिका ‘मुजीब’ तथा लोकस्वामी, लोकमत, मुस्लिम टुडे, यूनिवर्सल कवरेज, चौथी दुनिया, भारत भास्कर, दैनिक भास्कर, इंदौर समाचार पत्र, डेल्ही हंट, अमृतविचार, हरिभूमि, 4 pm, दैनिक जनवाणी, जनहित इंडिया, प्रातः काल समाचार पत्र, मीडिया केयर, देश रोज़ाना, उजाला, विशेष दृष्टि तथा सिटी एयर, क़ुतुब मेल, फॉलोअप, समाचार वार्ता, पार्लियामेंट स्ट्रीट, पैरोकार वार्ता के अलावा अनेक प्रतिष्ठित वेबसाइट और अनेक अखबारों में प्रकाशित हों चुकी हैं।