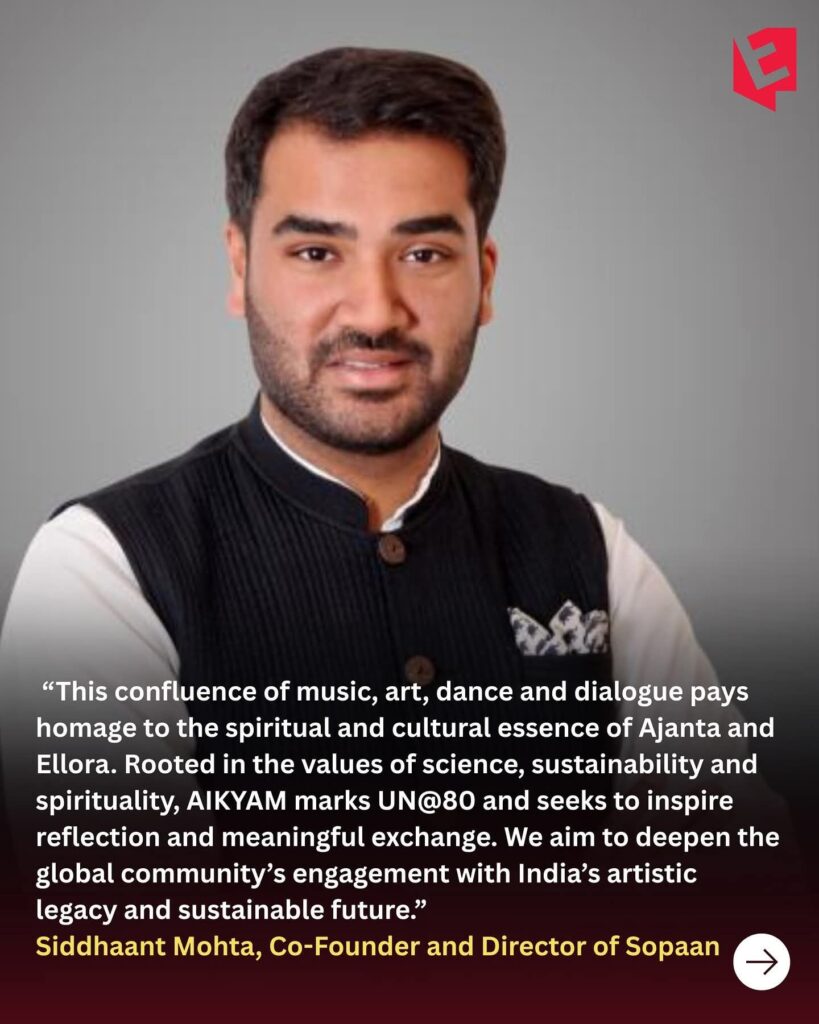

Habib Tanvir (Courtesy Outlook)

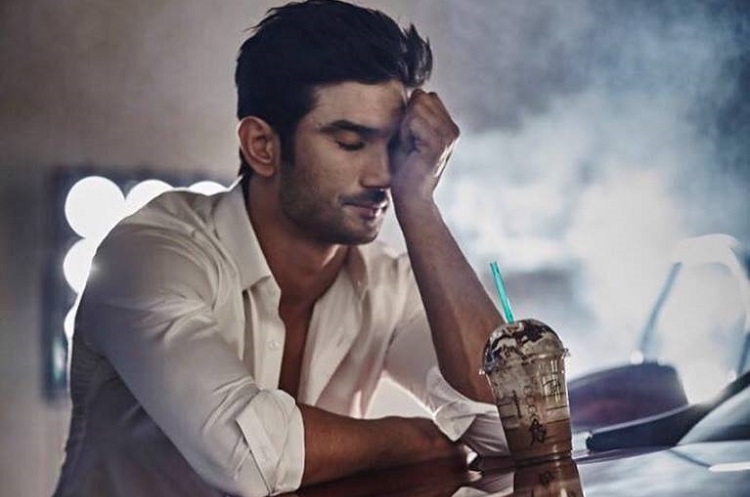

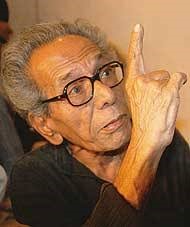

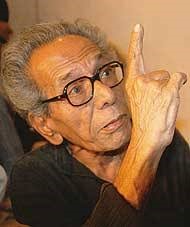

Habib Tanvir (1923-2009), was perhaps the most famous Theatre personality in north India. An actor-manager in the Old-School mould, he led a crowded professional life, which, over the years, had invariably spilt over into private moments with family, friends and lovers, often to detrimental effect. The Raipur-born Habib Ahmed Khan assumed the nom-de-plume of Tanvir after he started writing poetry in Urdu in his senior years at school. He rose to fame as the founder-director of Naya Theatre along with his wife, Moneeka MisraTanvir, a strong,dedicated and talented theatre person in her own right. The actors were from the folk-theatre of Chattisgarh, near Raipur in Madhya Pradesh. It was through his unknown but highly accomplished actors and actresses that Tanvir was able to create a body of work in the Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) theatre that stands alone. Two plays that come to mind and were hugely popular in their time, are Agra Bazar, based on the times of Nazir Akbarabadi( d-1830), the great Urdu poet, and, Charandas Chor taken from a Chattisarhi folk tale. Not without reason, he has remained for many, the most important director- playwright in the region. He was, for all his artistic accomplishments, a sadly flawed man. Without purporting to be a review of his memoirs, simply titled ‘’Habib Tanvir : Memoirs’’, (publisher-Penguin-Viking) this piece is a rebuttal of some of its contents to set the record straight.

The book is a translation from the Urdu by Mahmood Farooqui, a well-known historian and performer of Dastangoi, a near extinct art of story-telling, popular in 19th century Avadh, of which Lucknow was the cultural centre. Habib Tanvir’s life has been reconstructed through a series of remembrances dictated to Farooqui. One of the problems to arise from such an excercise is the propensity of the person remembering, to distort facts that may be too painful or embarrassing to remember. There were many such instances in Tanvir’s life but his letting down of Barbara Jill Christie nee Macdonald, a fine trained singer from Dartington Hall, Devonshire, England is the worst because it had a far reaching psychological effect on Anna, the talented singer daughter born of this relationship, on Nageen , his daughter from his marriage to Moneeka. The shadows of Anna and her mother Jill, through no fault of their own, always hovered over Nageen and her late mother Moneeka. Tanvir continued to visit Anna and her mother Jill, in England and France till 1996, when he was seventy three.

When Habib Tanvir had first met Jill, in England, he was thirty two and she, an easily impressionable sixteen. The year was 1955. He was handsome, dashing, a poet, and a student at RADA (Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts) in London. There was no Moneeka Misra then, on the horizon. He was already a man of the world, though with the airs of an idealist. It was easy to capture Jill’s heart. She loved him with a kind of sincerity and intensity that possesses the starry-eyed young, who in their optimism can go through hell and high water in search of the pure and the beautiful. One must also remember that when Habib and Jill had met the Second World War had ended only eight years ago, and the world, then as now, was desperately in need of love and hope.

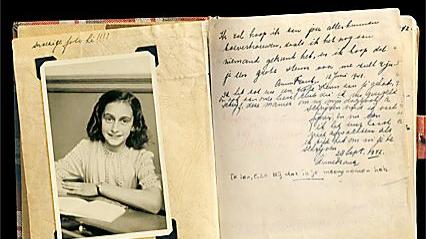

It was indeed a pleasure and a revelation meeting Barbara Jill Christie and Anna, a couple of years earlier at the India International Centre in New Delhi. An elegant, handsome lady of seventy two, Jill, came across as a cultured, really educated, as opposed to highly literate, though she was that too, person who viewed the past, that is, her relationship with Habib Tanvir, with warmth, and a certain detachment. She was quite aware of the fact that in spite of being treated irresponsibly by him, she had played an important role in his life, not the least because of Anna, their daughter and the three grandsons. Anna’s first son, Mukti, is eighteen; his grandmother has addressed her memoirs titled, ‘’Dreaming of Being’’ to him. The recollections are written as a long letter to him, interspersed with his grandfather Habib’s letters written to Jill, his grandmother, over a period of nearly twenty years; beginning in 1955, and with the last letter dated 15 April, 1964.

The following quotation appears on page one of the manuscript:-

“The desire to write a letter, to put down what you don’t want anybody else to see but the person you are writing to, but which you do not want to be destroyed, but perhaps hope may be preserved for complete strangers to read, is ineradicable. We want to confess ourselves in writing to a few friends, and we do not always want to feel that no one but those friends will ever read what we have written.”

_ T S Eliot

This beginning, on a note of seriousness, is sustained throughout the narrative of 153 pages. Barbara Jill Christie writes with deep but controlled emotion and respect for her chosen subject.

Anna Tanvir has written the foreword to her mother’s Memoirs. She begins thus, “ I first read my father’s letters written to my mother a few months after his death. I was sitting in the aeroplane on my way to India to attend a festival celebrating his life and work that was taking place in Bhopal in October 2009. It was a confusing moment as I had not been to the state funeral held in held in Bhopal a few months earlier, and had not had the time to absorb the finality of his absence, nor was I sure why I was undertaking this journey at this particular moment. I simply felt I had to go to where he lived, meet the actors of Naya Theatre whom I knew well, and meet my Indian family; I needed to be in India, on his home-ground, to properly accept that he was no longer physically there.“

Nageen, Habib and Moneeka’s daughter, and Anna’s half-sister, always remained deeply unhappy at her father’s philandering with various women over the years, though she would dutifully accompany him when he visited Jill and Anna in England and France in his old age. Once, in Exeter, Nageen, having gone to stay with Jill and Anna, turned hysterical. She kept saying that Jill did not really know Habib, for the compulsive womaniser he was. She also held Jill responsible for her mother’s continuous unhappiness. Nageen, all too aware of her father’s failings, loved him unconditionally. She could not tolerate the fact that she had to always share her father’s love with Anna and Jill. Habib, in his old age called Anna and Jill, “my two pearls”. He was spot on. Anna, born in Ireland, seven months before Nageen, is a gifted singer and has several albums to her credit. Nageen is a fine singer of the folk songs of Chattisgarh she learnt from the actors in her father’s troupe, is also a trained singer, she has also learnt Hindustani vocal music from the famous Salochana Yajurvedi. Anna and Nageen continue to be distanced from each other.

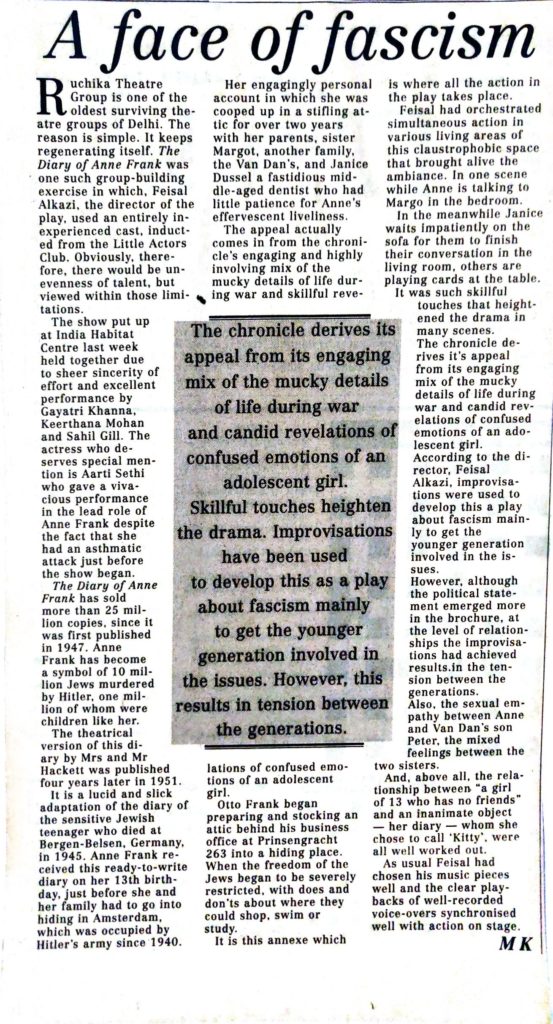

The release of Habib Tanvir’s memoirs on 28 May, 2013 at the Habitat Centre, New Delhi was a sham Public Relations job. Translator Mahmood Farooqui went on stage with Nageen, and together the two, lionised the deceased Tanvir. The announcer, a young lady, set the proceedings in motion by calling him one of the greatest Indian theatre directors of the 20th century; a fact that can be challenged by the serious followers of the work of Shambhu Mitra, Utpal Dutt and Ajitesh Bandopadhyay, all stalwarts of the Bengali theatre, and Jabbar Patel, a major figure of the Marathi stage. It was a veritable love-in, where critical judgement had been completely suspended. Habib Tanvir, the uncanny spotter of talent hardly got a mention. He was instead hailed as a messiah of Indian theatre, who worked with hardly any props, in the last twenty five years of his career. No one said while his minimalist approach was often very effective, he was not the first to use it well. There was not a word about Jill and Anna, for all practical purpose they did not exist. They are mentioned, albeit in passing, in the closing portion of the book. What Tanvir, with his cavalier attitude to facts related to his private life, could not ignore, his craven fans did.

As stated earlier, this is not a review of his memoirs but an attempt to redress a wrong committed fifty years earlier. Habib,, at forty, is still playing the ‘young Lochivar’; this is after his marrying the constant, deeply loving but neurotic Moneeka, and the consigning of Jill far into the background. In a letter dated 21 December 1963, written to Jill from Raipur, MP, he says thus :-

Dearest Jill,

Yes, I know. You have every right to feel sore. It is five weeks since I arrived. Well, this is the first time I am writing any letter at all. But darling, not for a day have you ever been out of my mind. I was having the sweetest thoughts about you and your wonderful letter was so welcome. It came in very good time. And I began to visualise all kinds of lovely things about you. Actually this is the first time we have ever shared life at all properly and for any length of time – and the whole things haunts.

He proceeds to tell about the acute paucity of funds and how theatre groups were falling all over him to work with them. To quote from the letter once more, “My mind goes back to each detail whenever parallel situations occur striking a contrast and I even think of the peace with which we shared our monies. Oh thank you so much Jill darling for all that most wonderful period of time”. Jill, writing to her grandson nearly fifty years after receiving the letter said, “I like this letter so much Mukti and I remember being overjoyed to get it – the longest Habib ever wrote to me and full of warmth and interesting news.”

Domesticity never suited him, though he had schooled himself into accepting it, lest he seem an ingrate to Moneeka and Nageen, and vital, rejuvenating romance that had awakened the artist in him after he fell in love with Jill, became a dream he could not sustain with any degree of consistency or loyalty. He was cleaved right down the middle of his being, if such a thing were possible.

Jill remembers in her memoirs, “By this I was still living in London but had to move into the house of a friend called Betsy Phillips, a rare and wonderful being. She had been an art teacher who taught me when i was a child. I had loved her lessons and we had always kept in touch. … She was not censorious, either of myself or Habib, nor particularly worried, which was most unusual under the circumstances! She seemed to be more than a little excited that a baby was coming along. I think the idea of a new life appealed very much to her sensitive, creative nature and she knew that I had loved Habib for many years, and that I would cope. That such a thoughtful person actually believed in me was indeed a great help.”

Habib ‘s take on Jill, her pregnancy, and then motherhood, in his memoirs is weary and resigned.

“Somehow, Jill managed to trace me in Dallas, Texas, and landed there. From there she accompanied me to New Orleans, East Virginia and Washington D.C. and stuck to me like a shadow. This was a great phase for my poetry. .. I came back via London and went to Edinburgh from there. Jill’s dream eventually bore fruit. Anna was born on 6 May 1964. Later Jill married Christie who gave her another daughter. … When both daughters joined school, Jill wanted them to have separate identities – one should have Christy as a surname and the other should be called Tanvir. She sent me the school form, and I signed it and sent it back. … But Moneeka did not like it.” (pg 308, Habib Tanvir : Memoirs).

He goes on to say how Moneeka, who had earlier lost their first child in Panchmarhi, had three miscarriages in quick succession. This was after Tanvir’s return to Delhi in 1963. Thanks to the timely intervention of Sheela Malhotra, who advised Moneeka to use a bolster under her feet while lying down, Nageen was born 28 November 1964. “Moneeka was amazed and always considered Sheela to be Nageen’s second mother.” (pg 308, Habib Tanvir : Memoirs).

Habib’s life, over the years, thus rolled on amongst the comings and goings of girl friends, with whom, to his amazement, Moneeka, invariably bonded! Jill, of course was an exception, she was the great love of his life and the mother of his child, and so, was the ‘outsider’ whom, Habib, could neither forget, nor give up. He visited Mother and daughter, whenever he could. His silence, for some years following the birth of Anna was, in retrospect, not inexplicable. He just did not know how to accept responsibility for his actions, especially in his private life, not that he would acknowledge, much less accept, responsibility for his feckless and even cruel behaviour towards colleagues in his professional life. Deep down inside he seemed to be convinced that since he was an artiste, he was entitled to behave as he pleased.

Habib Tanvir’s training in England in Theatre, first at Rada in direction, following which, a stint in acting at the Bristol Old Vic, cured of participating in the joys of the proscenium theatre and the dramaturgy it required. He was for a more spontaneous kind of theatre that had its roots in the Indian soil, where sets and props were imaginative, and could be carried in a couple of suitcases and actors could express themselves with ease and freedom. 1954, found him working with Begum Qudsia Zaidi’s Hindustani Theatre in Delhi. She had managed to gather around herself several talented artistes, amongst them Habib Tanvir, the Hyderabadi Urdu poet Niaz Haider, the music composer from Bengal, Jyotirindranath Moitra, who had at one time or another been associated with IPTA ( Indian Peoples Theatre Association), the cultural arm of the Communist Party of India

Hindustani Theatre did three Sanskrit plays, Mriccha Kattikam by Shudraka, Shakuntala by Kalidas , and a play each of Bhasa and Bhavbhuti. It was with Hindustani Theatre that Habib Tanvir did his first production of Agra Bazar comprising tableaux of life in the times of Nazir Akbarabadi, the great Urdu poet whose verse sang of the joys and sorrows of everyday life. Habib was to tinker with the script over the years to make it more expressive and lively. Agra Bazar opened the doors to fame and Charandas Chor confirmed it. The grand success of this play was largely due to its blend of satirical comedy and high seriousness. The idea came from a Chattisgarhi folk tale, and which was brought sparklingly alive by a set of actors from there. Charandas Chor with its cast of folk actors, toured internationally, conquering the hearts of audiences everywhere despite its script being in a dialect from Madhya Pradesh.

It was the actors who did the trick with the plasticity of their body language and a gamut of emotions and ideas that their vocal inflections were able to convey to an audience that did not ostensibly understand the language in which the play was written.

Tanvir’s relationship with his actors had always been fraught on and off the stage. In spite of his wide and varied learning he was a little afraid of his actors, most of whom were barely literate. Why? Was it because they possessed an unusual amount of native artistic intelligence and so were able to convey his ideas with ease? It was widely said that they had to be coached in minute detail in the course of the rehearsals. This may have been true in the case of certain actors but certainly not with the gifted ones. His actors were already known names in the folk theatre of Chattisgarh.

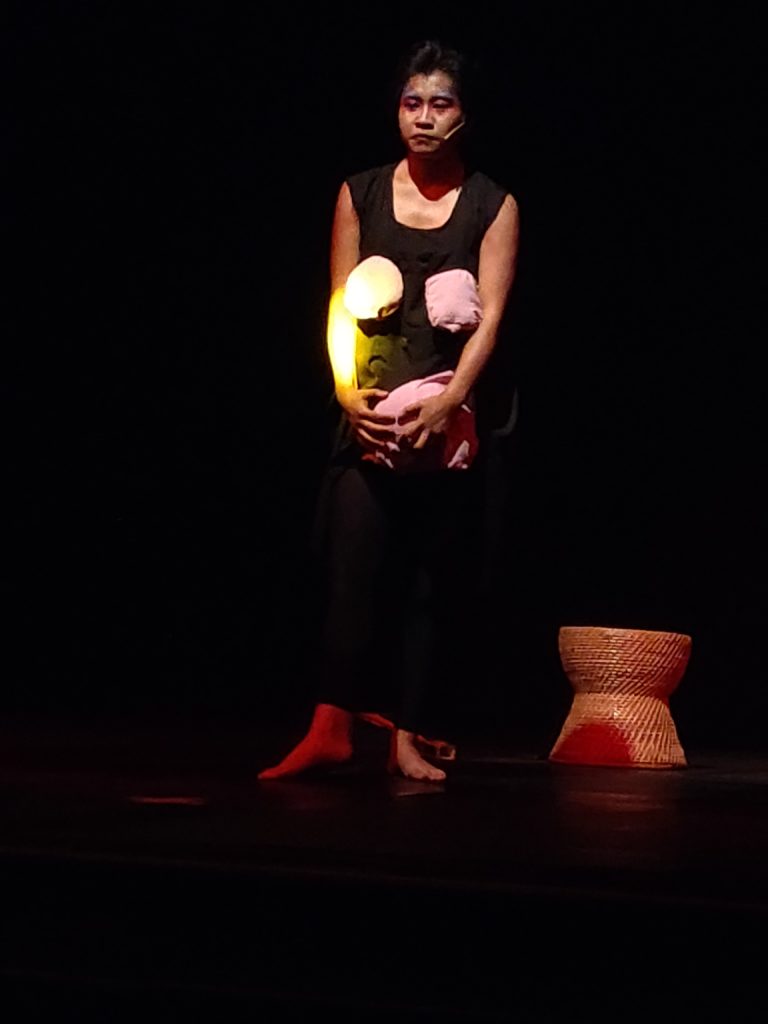

Laluram, Punaram, Majid, Bhulwaram, Madanlal, Fida Bai, Teejan Bai, are some of the actors that come to mind who graced the plays staged by Naya Theatre. They were, like some who came in their wake, marvellous, and brought the intentions of the playwright, be it Habib Tanvir or Shakespeare, yes! Habib did do a Chattisgarhi version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream! These were poor folk who worked as farmers and artisans, did a little folk theatre, of which Naacha was an essential part, were discovered by Habib and brought to live and work in Delhi in the Naya Theatre plays.

These actors and actresses were poor in their villages and they remained poor in the Metropolis of Delhi. It was a lot more difficult to survive economically in Delhi, where day to day living was murderously expensive. In their villages in Chattisgarh, they could somehow get back, possibly by sharing their meagre resources. Life in Delhi offered no such consolation. Habib had very little money but he was loath to share it with the actors who had made him famous. Theatre is an actor’s medium. It is the actors who bring to life a director’s vision once the performance begins onstage. Habib’s actors from Chattisgarh, served him very well for a long time, but he had little for them once the play was over. The actors led a miserable life, while he managed to lead economically, an acceptable middle-class existence.

Habib had scrounged around for ‘pennies’ till his early forties, but once he found his actors to interpret his vision of the theatre in the Chattisgarh folk idiom, his fortunes began to change rapidly. He managed to slowly but surely stabilise himself economically. The grants that he got from various state institutions were barely adequate to run his drama company. And what was coming in (from performances abroad) he did not share with the actors. His attitude was, if the Government grants were insufficient to pay his actors, so be it. It was inevitable that his actors go on strike and they did when they and Habib were staying in a number of tiny Government flats in Ber Sarai, New Delhi, in the early 1990s. They went public with their grievances, saying that they knew that Habib had money, but he did not want to give what they thought was owed them.

Habib Tanvir’s career, since his association with the Chhatisgarh actors, progressed steadily. The Government of India first awarded him the Padmashree, and later, the Padmabhushan. The Madhya Pradesh state government, then Congress-led, honoured him and gave him a decent flat to live in. He showed exemplary courage persisting with the production of his play, Ponga Pundit, about religious hypocrisy, when activists of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and allied organisations of the Hindu Far Right, made repeated violent attempts to disrupt performances, after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. His Leftist political upbringing, with its emphasis on the exercise of discipline when under siege, came in handy. When the end came he was given a state funeral in June, 2009.

He had the privilege of courting the Soviet Union, and finding life-saving employment there as a Dubbing artist, and the United States of America, where he was invited as a speaker on theatre, and later with Naya Theatre Troupe, for performances. East and West Germany before the cold war, and then plain Germany, after the fall of the Berlin wall along with Poland were favourite destinations for work as were England and Scotland; the production of Charandas Chor with Chattisgarh actors was highly appreciated at the Edinburgh and won the Fringe First award.

As far as his sense of entitlement was concerned, he knew how much he could ‘squeeze’ in a relationship. Women continued to drool over him even in old age, as he smoked his pipe with a preoccupied air. Moneeka and Nageen, as wife and daughter, performed their filial duties with unflinching devotion. Moneeka passed away on 28 May, 2005. After having attempted suicide over Habib, as a young woman, she became indispensible to him, without her support he could not have gone very far in any direction. After her mother, went, Nageen looked after her father very well. The young, particularly those inclined towards the political Left came in droves to worship at his feet. Habib Tanvir had done very well for himself. There are two other participants in his story, namely Jill, the great love of his life, whom he had let down, and their daughter Anna.

When Anna was born in Dublin, her father Habib Tanvir was far away in India. His deafening silence worried her mother Jill terribly. Writing in old age to grandson Mukti, she recalls :

I wrote to Habib and sent pictures, but received nothing in return. You ask me Mukti what I thought had happened? It occurred to me that he might have died, or at least become ill. I read and re-read that last letter with its cool beginning, its preoccupation with theatre productions and its wistful air at the end. At the time I simply didn’t know, but felt that if no disaster had befallen him, he must have withdrawn. It was a horribly chilling sensation to feel that closeness simply disappearing as if it had never been,with no explanation. … Having a small person to care for who took up almost every waking moment meant I did not sink into despair. Even so his silence was insupportable; a dead-weight on my life, and totally bewildering. Looking after my dark-haired daughter who I so badly wanted him to see, made me wonder each day what momentous happening was stopping him from being in touch.’’

After two years of silence Habib responded to a letter from Jill informing him of her brother Kev’s death. Jill remembers, ‘’ I was surprised to get a reply. He wrote rather formally but comfortingly and asked after our daughter Anna, saying he would love to see her one day. … At long last, he did manage to come to see us, and continued to visit from time to time right up to the end of his life. There remained a genuine fondness between us and always unspoken efforts on his behalf to put things right.”

Anna responds to her father Habib’s absence in her childhoodin the Epilogue to her mother’s memoirs :

My first meeting with my father was unforgettable. It was not until I was nine years old that he came to meet me, by which time my mother had married, and I had a half-sister Vickie, who was as fair as I was dark. I spent my childhood conjuring up his image in my imagination, inventing him over and over again, in more and more exotic colours. My mother had always talked of him, trying to give me a sense of my Indian heritage through her stories and descriptions. … My father accompanied us in our daily lives in the imagination, and for me his image was so strong that he was somehow present despite his physical absence.”

Anna remembers her first meeting with her father:

“ He arrived clutching a chillum pipe that he puffed continuously that he puffed at continuously clouding him in wreaths of smoke, and wearing a large colourful shawl, a beret, a hand-made kurta and stylish jeans. … He seemed to create magic wherever he went, and as for telling a story without a book, he recounted to me hour after hour stories from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, and I was utterly mesmerised.”

Anna and her mother Jill loved Habib devotedly, despite the years of absence and neglect, and that things came a full circle to bring hope and optimism before he passed away is indeed lovely.

Courage in his private life had never been Habib Tanvir’s strength, despite professions of often real love towards those he had, in some way, wronged. He gave Nageen exclusive rights over all his writing, including his correspondence. She is not keen that her father’s letters to Jill, and, hers to him should ever be published. It is perhaps out of a misplaced sense of loyalty to her mother Moneeka’s memory that she is acting in this manner. Who would know better than Nageen, how much her mother and Jill had suffered because of her father’s irresponsible behaviour towards both. It is time for a mature reconsideration of the past. It is time to let wounds heal. It is time to look forward rather than back. It is time to understand that life is the source of all art and that artists are, at once, both strong and frail creatures, who are but mortals.