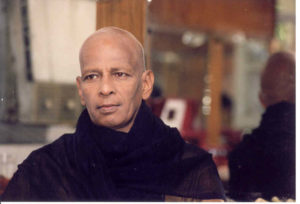

“The retrospective of my films has come 20 years too soon” (Sudhir Mishra to Shumita Didi)

“The retrospective of my films has come 20 years too soon”

But who’s complaining – Sudhir Mishra talks to Shumita Didi

Shumita: How does it feel to have the first ever Retrospective of your films at the relatively young age of 51, and that too at Delhi ?

Sudhir: “This has come to me twenty years too soon I feel, but I am grateful to be showing the body of my work. I think I hardly the know the boy who made “Yeh Who Manzil Toh Nahin”… An important time in my life from the age of 21 when you form relationships, first meet very good people like Badal Sircar, Safdar Hashmi…was spent at Delhi. By virtue of being here I could soak in the vibrant atmosphere at JNU and Delhi University, get exposed not only to the best of world cinema but also the finest of theatre productions like the NSD Repertory’s work, the Sriram Festival; It was wonderful to be able to savour the rich amalgam of NSD, Triveni, Rabindra Bhavan, LTG, Sriram Centre- at Mandi House. There was an explosion of talent in all fields roughly in the period ’78-’81 when I was here. Even when I left for Bombay, my Father had been posted to Delhi so it was home. Many connections and references stem from here. We belong to Lucknow though.”

Shumita: The opening film was, “Hazaro’n Khwahisein Aisi” . It has risen to almost cult status. How do you feel about this film? What is the essence of this film?

Sudhir: “It has acquired a life of its own. People enter a film through many doors. They have come up to me and explained in it things, way beyond what I had intended. All the actors were new or relatively unknown so it was a challenge in many ways. Sometimes I feel a much appreciated film becomes a mill around your neck! As far as audiences of that film go, you just cant match it! So I often say, I have disowned that film! But it has a very wide range of viewers. I have seen it with students at IIT’s, IAS Wives Associations, Policemen, Politicians….I think this film is a soft film even though it talks of many harsh realities. It talks of and touches the vestiges of purity left in each one of us even when we have lost our idealistic youth. I was very moved when after watching the scene on police brutality, a young policeman came up to me with tears in his eyes and said, this is exactly how they make us do it.”

Shumita: Did’nt you face censor trouble with this film? There are many scenes where I wondered eg Police violence, party politics etc?

Sudhir: “I would love to say I did! I became a film-maker at a time when if your films weren’t agitated against, or heavily censored they perhaps lacked something! But actually I was lucky. I only had to make one small cut in a scene where there was a close up of a banner saying All India Youth Congress, so I replaced it with a wider shot of the same banner, and no one noticed! The irony was that this was during the BJP regime. They were being sensitive to the Congress sentiments! It was released during the Congress regime though. In India I think politics and violence do not evoke as much of sentiment than lets say if it was a film on religion.”

Shumita: All your films have had varied themes, “Main Zinda Hoon” “Dharavi”, “Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin”, “Chameli”, “Calcutta Mail”…some very down to earth, a thriller, some fantasy woven in..Which would you say is your favourite film from all of them?

Sudhir: “ It’s not a wrestling match! I think for a Director for the most part it is like being a parent, you like them all and particularly the one you are immediately involved with. But I would say Khoya Khoya Chaand for now. I liked Chameli, it was a fairy tale. Calcutta Mail I disown! Except for a few sequences I don’t like that film it has too much happening in it. But interestingly when I was visiting a beaurocrats party at Washington, no one seemed not to know who I was, what films I had made etc till someone said, he has made Calcutta Mail. And then I was suddenly mobbed!”

Shumita: Any particular reason why you’ve cast Soha Ali Khan in three projects running, Khoya Khoya Chaand, Tera Kya Hoga Johnny” and “Mumbai Cutting”….? You’ve worked with Shabana, Deepti, Smriti, Chitranghada,… Do you ever get involved with the beautiful women you work with?

Sudhir: “She is a good actress. I feel her potential and different facets of performance are being explored in all three films. I have no qualms about repeating actors according to role requirements..I have also first cast and repeated Shiney Ahuja, and Saurabh Shukla for example is in most of my films. As a director and storywriter I feel very grateful to the actors who bring alive a character I have written, envisaged. To that extent one gets involved with them as bringing to life your characters. If you are talking of romantic involvement with any of my actresses, no, that would be too dangerous!”

Shumita: Well, in “Yeh Who Manzil Toh Nahin”, you had cast Sushmita Mukherjee, and she was your wife then! What is the main theme of “Tera Kya Hoga Johnny” and why did you feel the need to write and make this film. Is it a short film/ feature length?

Sudhir :“In a Bombay trying to be Shanghai, who gives a damn for a young man/boy who sells coffee? But there are some who do. Three characters, played by Neil Nitin Mukesh, K.K. Menon & Soha Ali Khan care about this boy in different ways and their life stories unfold through his eyes. Both wonder what will happen to each other. It is a feature length film.”

Shumita: What of the film, “Mumbai Cutting” you are doing as part of an 11 director package? What is the relevance of such a concept? I believe the other directors apart from you are..Kundan Shah, Jahnu Barua, Anurag Kashyp, Ruchi Malhotra…

Sudhir: “Yes, and Rituparno Ghosh, Rahul Dholakia, Munish Jha, Revathi, Ayush Raina, Shashank Ghosh…..Each film is roughly 10 mins duration. It is a great concept and more such experiments should be happening. It has been produced by a husband wife team Samrat & Niyati, with Sahara funding and will get a theatre release, plus a TV package. My story is set in almost real time where under the crowded J.J flyover, one of the busiest parts of Bombay, a murder takes place. Soha is in this film too alongwith Chitranghada Singh.

Shumita: She disappeared from the scene for a while, how is it working with her again?

Sudhir: “She saw the three films I had made and mockingly complained, how could you without me! I teased her back and said you are the one that vanished! Seriously though, I may not have gone looking for another actress if she had been there..

Shumita: So in a way that was good, because we got to see very different work from Soha.. I felt she was perfectly cast in Khoya Khoya Chaand. The olde worlde look was carried very well by her. Sushmita was in this film too, did you enjoy working with her after so long?

Sudhir: “She always had a great sense of humour and after my film, she is working with Karan Johar these days. I did get annoyed when I heard that she had taken her son to swallow raw fish to heal his asthma which subsequently got worse, I mean he is not my son, he is hers and Raja Bundela’s son, but I told her to leave the room. Told her after all her high education if she had gone and tried that, I want nothing to do with her!”

Shumita: She is a lovely person, good actress and a madcap! It is interesting how I was great friends with your second wife Renu Saluja, and I am great friends with your first wife Sushmita! They both gave me things that said “best friends forever” – uncanny. But it is really your brother Sudhanshu I got to know when working at CENDIT making documentaries..he went too soon as did Renu..

Sudhir: “Life is like that. There was a time when we were younger when everyone was somehow involved in a triangle! I was involved with someone who was involved with someone and so on…! Sudhanshu was a charmer, many women have come up to me after he died and told me how they felt about him with a glazed look in their eyes! He made some good films. Renu always used to scold me for being absent minded like I would get up from the table if I was done..she’d say I’m going to call up your Mother and ask her why didn’t you teach him table manners! The thing is, you live in two worlds simultaneously if you are a writer/director..I would be thinking of some character and wander off. That’s why I don’t drive!”

Shumita: Even though they are’nt on the floor yet, could you talk about the other two projects? “Aur Devdas” to begin with. I believe Anurag Kashyp is coming up with one too. Yet another Devdas film Sudhir! Although I believe you mentioned once it has some political content…?

Sudhir: “The initial bit is from there…characters e.g and then takes off in a completely different direction. The idea is that if say Devdas who had originally come from England, instead is heir to a political lineage…his mother is a Chief Minister, and Paro lets say is..the daughter of a Police Commissioner..and gets married into another poitical dynasty and becomes the “bahuji” there…then who would be Chandramukhi…..? Maybe she is the one that handles the money of the politicians..that which no one should know of. The story thus takes another trajectory.

Shumita: What of the film in which you plan to use music by Baba Ghulam Muhammad Chaand from Pakistan, the “Nawab and Nauthchgirl…” film? I hope that is still on?

Sudhir: Yes, I would like to use his compositions. He is a very interesting performer. That was a lovely evening you had arranged for us to hear him. This film is a sort of black comedy on 1857.

Shumita: What are your immediate plans? Heading towards Cannes this year? Do you find it relevant going there?

Sudhir: “I have to be back in Bombay for mixing tomorrow morning. If I get done, I may go for a week to Cannes before setting off to speak at a festival in Calcutta. Cannes is always an interesting place for cinema lovers to go to, discuss co-productions, get to meet colleagues from all over, and gauge your place in world cinema