AIKYAM 2025 Concludes at Ajanta–Ellora with a Vibrant Tribute to UN@80

By Kanika Bansal

AIKYAM Concludes at Ajanta–Ellora with a Vibrant Tribute to UN@80

Artists, scholars and delegates from over 30 countries convened over three days to celebrate India’s heritage and shared global values

India’s tourism sector is witnessing strong growth, with 20.57 million international arrivals and over 2.94 billion domestic tourist visits in 2024, reinforcing the country’s global cultural influence

In 2024, Maharashtra recorded the highest foreign tourist inflow among all Indian states, receiving 3.71 million international visitors

Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad), Maharashtra, November 22, 2025: Sopaan’s flagship cultural initiative, AIKYAM 2025, successfully concluded its three-day celebration (November 21-23, 2025) today at the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Ajanta and Ellora. The event marked the 80th anniversary of the United Nations through an immersive convergence of art, heritage, diplomacy and sustainability. Set amid the breathtaking rock-cut caves of Ajanta and Ellora, AIKYAM 2025 brought together global cultural practitioners, historians, artists and diplomats for a rare celebration of India’s timeless wisdom and living traditions.

The event witnessed the presence of key dignitaries from UNESCO, Maharashtra Tourism and the Municipal Corporation of Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, alongside ambassadors, diplomats and

cultural representatives from over 30 countries. Among the distinguished attendees were Shri Sanjay Khandare, Principal Secretary, Maharashtra Tourism, Dr. Timothy Curtis, Director, UNESCO Regional Office in India, and Shri G. Sreekanth, Municipal Commissioner of Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar. Their participation reinforced AIKYAM’s core message of global unity, responsible cultural tourism and the harmonious blending of tradition with modern innovation. Several senior diplomats, including the High Commissioners of the United Kingdom and New Zealand; the Ambassadors of France, China, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland, Spain and Thailand; and the Country Head of UNDP, also graced the festival.

Shri Sanjay Khandare, Principal Secretary, Maharashtra Tourism, said, “Maharashtra stands at the forefront of India’s tourism landscape, committed to becoming a premier global cultural destination, with the Ajanta and Ellora caves serving as living expressions of our civilisational depth and artistic brilliance. As we commemorate 80 years of the United Nations, we gather for AIKYAM, a celebration rooted in the philosophy of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, reminding us that the world is one family and reflecting Maharashtra’s legacy of bridging faiths, fostering art and inspiring unity across centuries. In 2024, the state recorded India’s highest foreign tourist inflow with 3.71 million international visitors. Our outlook remains strong as we continue to enhance infrastructure, visitor services and opportunities across key destinations. It is our goal that every traveller leaves with an experience that is enriching, memorable and deeply connected to our cultural soul. In the spirit of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, we hope Maharashtra’s cultural richness inspires harmony across nations and strengthens unity in diversity.”

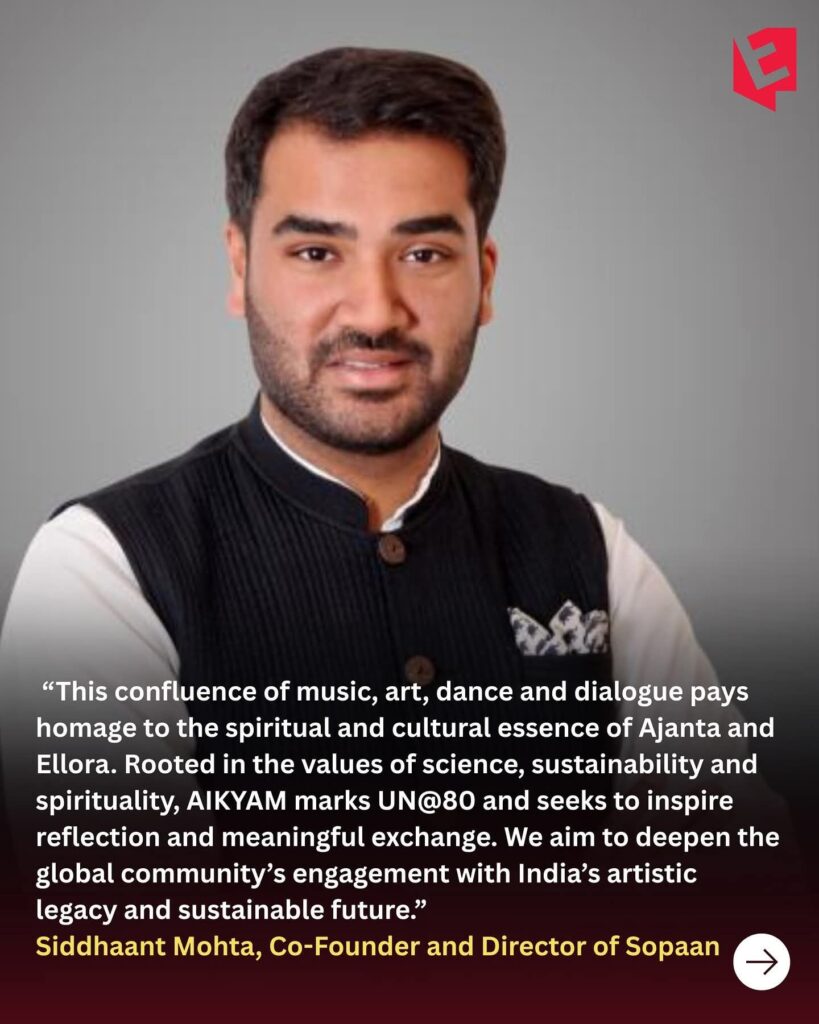

Siddhaant Mohta, Co-Founder and Director of Sopaan, said, “AIKYAM is a strategic initiative that reimagines how heritage, performance and dialogue can come together to build global understanding. Conceived as an immersive three-day journey, it transforms the sacred cave complexes of Ajanta and Ellora into living stages for unity and exchange. Drawing from Sopaan’s experience curating cross-cultural programmes with the royal families of Jaisalmer and Gwalior, and with the Delhi Government at Purana Qila, AIKYAM marks 80 years of the United Nations. We stand

at a global pedestal where we amalgamate a unique confluence of art, culture and spirituality to echo the United Nations’ founding ideals of peace, cooperation and a shared global future.”

Dr. Timothy Curtis, Director, UNESCO Regional Office in India, remarked, “Ajanta and Ellora, among the earliest Indian sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, stand as dynamic Indian repositories of philosophy, creativity, and shared human endeavor. Their legacy, rooted in artistic excellence, scientific prowess and in the coexistence of diverse traditions, reminds us of what humanity can achieve together. In a rapidly changing world, these sites call on us to renew our commitment to dialogue, cooperation and collective action. AIKYAM 2025 brings this spirit to life, demonstrating how cultural heritage is not just a record of human achievement but a roadmap for building dialogue, understanding, and collective action in the spirit of UN@80 and our shared future.”

Extending his welcome, Shri G. Sreekanth, Municipal Commissioner of Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, noted, “Celebrated amid the timeless grandeur of our UNESCO World Heritage Sites, AIKYAM beautifully bridges our cultural heritage with innovation. As we commemorate UN@80, this event highlights Maharashtra’s commitment to honouring tradition while embracing the future.”

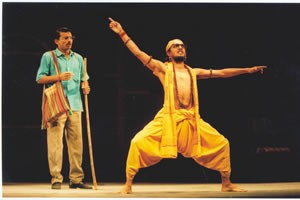

AIKYAM 2025, celebrating oneness, was a vibrant convergence of culture, heritage and global dialogue centred at the Ajanta and Ellora caves. As dusk gathered, the forecourt of the monolithic Kailasa Temple, Ellora, carved from a single rock to honour Lord Shiva, became an open-air amphitheatre. The evening opened with a Shiva Invocation by HH Maharani Raseshwari Rajya Laxmi of Jaisalmer and Nick Booker, whose Sanskrit chants and interpretations evoked the cosmic principle of Aikyam. This was followed by AIKYAM Omkara, choreographed by Gauri Sharma Tripathi and performed by international artists using Kathak, Bharatnatyam and Odissi, to embody the universal rhythm of creation, continuum and dissolution. Intellectually, the event featured a major lecture by historian William Dalrymple, “The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World,” which connected India’s civilisational ethos to the UN’s global vision, alongside talks by other thought leaders, including Dr. Timothy Curtis and Booker.

Complementing the performances and talks, the festival featured significant artistic and historical recreations, underscoring its theme of global cultural dialogue. A highlight was the musical recreation of the historic 1967 UN General Assembly concert by Pandit Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin, expertly performed by Pandit Shubhendra Rao and Dutch cellist Saskia Rao-de Haas, emphasising dialogue as audible harmony. Brazilian artist Sergio Cordeiro also contributed with a live mural reinterpreting the Ajanta murals in a contemporary idiom. The overall experience was enriched by curated heritage tours to sites like the Daulatabad Fort and Bibi ka Maqbara, textile showcases of Paithani and Himroo, and a celebration of Maharashtrian cuisine, culminating in contemplative visits to the Ajanta caves on the final day.

Cultural tourism accounts for nearly 40% of tourist arrivals in India, and the country’s heritage tourism market, valued at USD 19.9 billion in 2024, is projected to reach USD 27.1 billion by 2033. AIKYAM 2025 positioned heritage as a powerful tool for cultural exchange, sustainability and global connection, further strengthening India’s soft power footprint. Anchored in the philosophy of oneness of science and spirituality, humanity and nature, AIKYAM 2025 showcased India’s alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals while celebrating the artistic and spiritual genius of ancient civilisations.

Founded by Ambassador Monika Kapil Mohta and Siddhaant Mohta, Sopaan continues to build immersive cultural journeys that honour India’s heritage while fostering meaningful global dialogue.

As AIKYAM 2025 drew to a close, the resonance of its message remained clear, that culture, when shared, becomes a bridge between people, nations and the collective future of humanity. The success of the festival was supported by its key partners and sponsors, including Endurance Technologies, Trident Group, JSW, RMZ Corp, VFS Global, TVS Motors, Bharat Forge, SPP Pumps, Volvo, Kalpataru Projects, CBSL Group, ZF Group and IndiGo.

About Sopaan

Sopaan crafts rich, bespoke events that represent Indian cultural heritage on the world stage, bringing historical sites alive in a contemporary context and creating meaningful cross-cultural connections. By blending music, dance, fashion, painting, sculpture, textiles, cinema, architecture and cuisine, Sopaan creates enriching sensory experiences that celebrate India’s living culture with ancient roots and an exciting future. With a mission to craft the world’s cultural connections with India, Sopaan has partnered with state governments, royal families and renowned curators to showcase the country’s incredible history and extraordinary people against the backdrop of its timeless heritage.

About Maharashtra Tourism

The Government of Maharashtra is committed to promoting the state’s diverse tourism offerings, spanning heritage, culture, nature and adventure. With world-renowned destinations such as the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Ajanta and Ellora, the vibrant cities of Mumbai and Pune and serene hill stations like Mahabaleshwar and Lonavala, Maharashtra offers a rich tapestry of experiences. Through initiatives that enhance infrastructure, promote sustainable and eco-tourism and celebrate cultural festivals such as the Ganesh Festival and Hindavi Swarajya Mahotsav, Maharashtra Tourism continues to highlight the state’s unique heritage and vibrant spirit while ensuring memorable and responsible travel for all visitors.

Media Contact:Kanika Bansal: +91 98995 74833, kanika.b@jaibo.com

Anjali Sharma: +91 98993 02902, anjali.s@jaibo.com