A Living Celebration of Folk Traditions at Kala Sankul on Basant Panchami

At Kala Sankul, the art centre of Sanskar Bharati, New Delhi, a monthly symposium dedicated to folk arts and Indian cultural traditions was held on 23rd and 24th January 2026 on the auspicious occasion of Basant Panchami. Conducted in a dignified and emotionally resonant atmosphere, the two-day event emerged as a vibrant celebration of India’s folk consciousness, artistic devotion, and cultural memory.

The first day began with the ceremonial worship of Goddess Saraswati, invoking wisdom, creativity, and artistic insight. Scholars, artists, and cultural practitioners participated in the ritual, creating an ambience of serenity, contemplation, and spiritual warmth that set the tone for the days ahead.

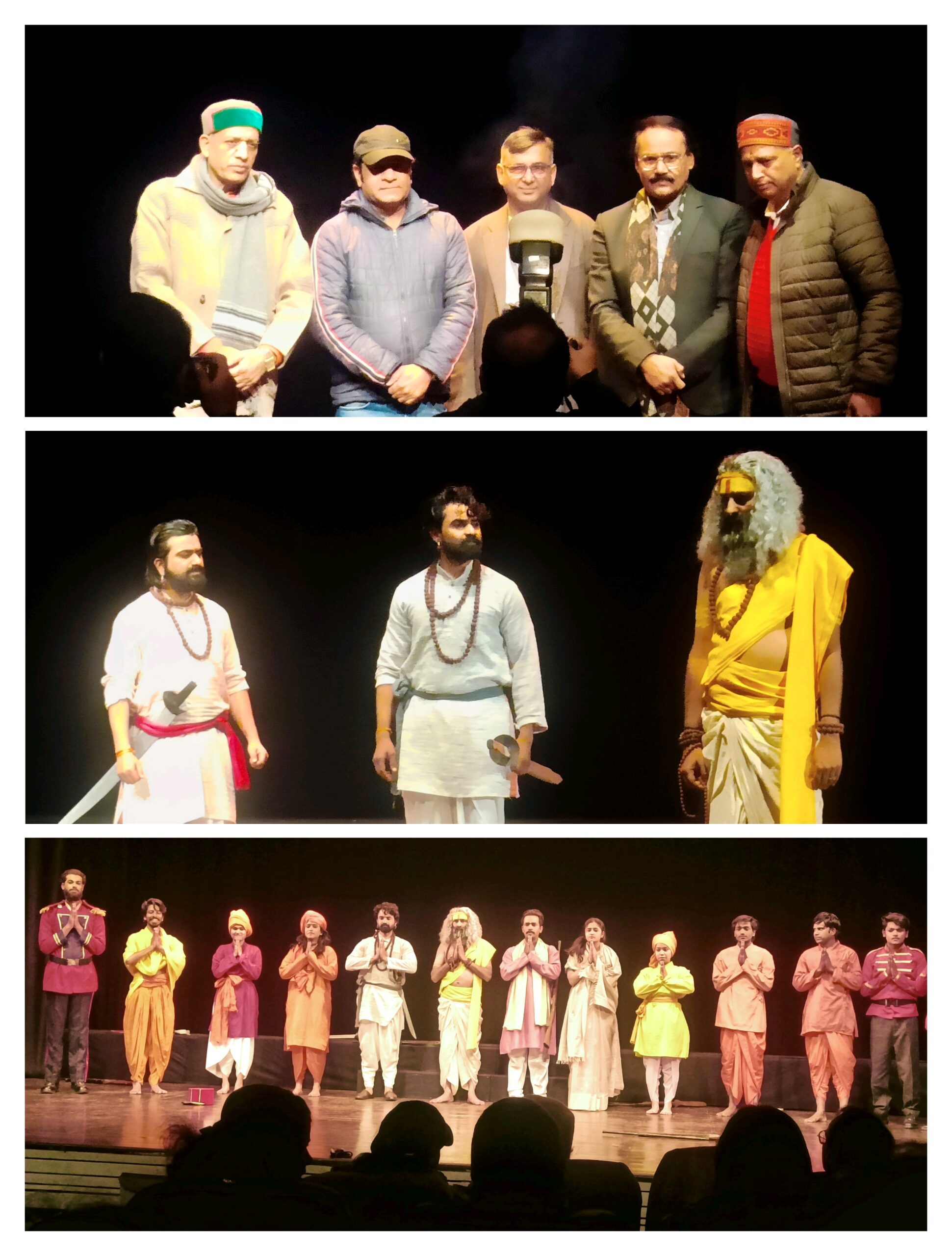

The cultural evening on the second day, held at 5:30 PM, unfolded as a memorable showcase of India’s rich folk heritage. The programme commenced with the lighting of the ceremonial lamp by Sh. Ashok Tiwari, Central Office Secretary; Sh.Sanjay Kumar Poddar, Provincial General Secretary (South Bihar); Shruti Sinha, Symposium Convener; and Mrityunjay Kumar, Monthly Coordinator. Under the gentle glow of the lamps, the stage seemed illuminated by the very spirit of India’s folk traditions.

Folk vocalist Chandni Shukla captivated the audience with her melodious singing, reflecting the simplicity and sweetness of rural life. Her songs carried the fragrance of the soil and evoked memories of village landscapes. This was followed by a soulful Saraswati Vandana presented by renowned artist Amit Kumar, which filled the auditorium with devotion and reverence.

The sequence of folk dances presented a vivid tapestry of regional traditions. The Jhhijhiya dance, performed by Akanksha, Nishu, Dipriya, Rinkle, and Aastha from Purnia, beautifully expressed collective faith and folk spirit. This was followed by the energetic Jat-Jatin dance by noted folk dancers Uday Singh and Shruti Mehta, whose rhythmic vitality held the audience spellbound.

The Sama-Chakeva dance, performed by Shruti, Pratiksha, Rajnandini, and Shambhavi, conveyed delicate feminine emotions deeply rooted in folk life. The evening concluded with vibrant presentations of Jhumar and Kajri, filling the atmosphere with joy and festive exuberance.

These performances were not merely artistic displays but living expressions of traditions passed down through generations. Every rhythm, movement, and melody reflected the depth of India’s cultural memory.

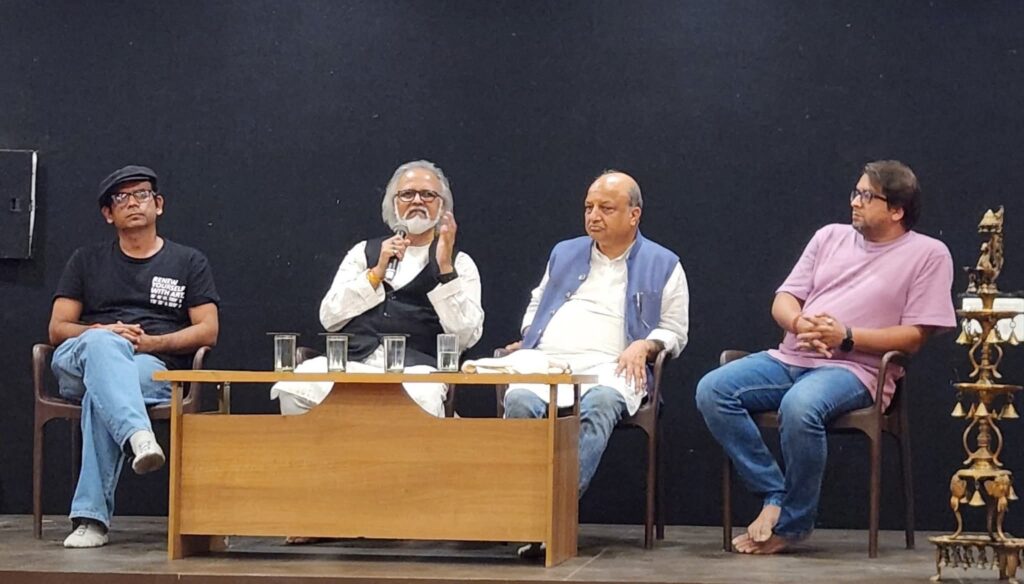

The monthly symposium stood as a meaningful initiative towards the preservation, promotion, and transmission of folk arts to younger generations. The presence of art lovers, intellectuals, and young audiences added depth and significance to the event.

At the conclusion of the programme, all participating artists were honoured with ceremonial shawls by Abhijeet Gokhale, All-India Organisation Secretary, and Ashok Tiwari, in appreciation of their dedication and artistic commitment.

The programme was conducted with grace and clarity by Garima Rani, while Shruti Sinha, Symposium Co-convener, delivered the vote of thanks. The success of the event was made possible through the dedicated efforts of renowned announcer Bharti Dang, Programme Coordinator Mrityunjay Kumar, Brijesh Kumar, Harshit Goyal, Vijender Kumar, and Ritambhara.

This gathering became a cherished cultural memory—where folk art re-emerged with beauty, dignity, and heartfelt warmth.