A Graceful Beginning: Inauguration of the Padmashri Daya Prakash Sinha Theatre Studio & Art Gallery

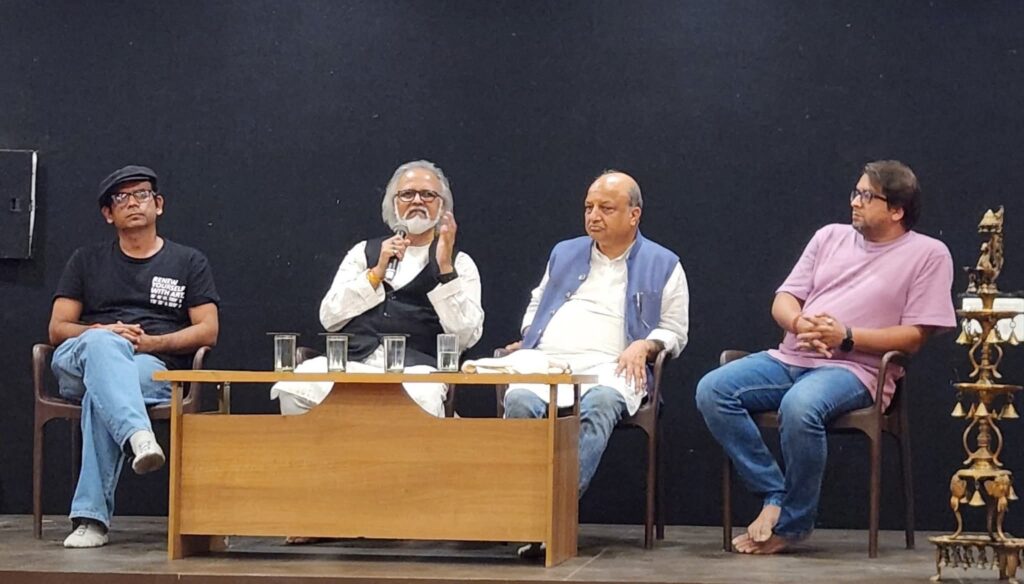

Delhi witnessed a moment of cultural significance as the Disha Group of Visual and Performing Arts inaugurated the Padmashri Daya Prakash Sinha Theatre Studio & Art Gallery on 2–3 December 2025. The ceremony, dignified and heartfelt in its essence, was formally opened by Shri Somesh Ranjan, senior social worker and son-in-law of the late Daya Prakash Sinha. The event brought together eminent personalities from the fields of art, culture, education, and theatre — including Subodh Sharma (RSS/Sanskar Bharati), veteran theatre artist J.P. Singh, senior critic Anil Goyal, theatre personalities Shyam Kumar and Anil Sharma, critic-performer Munmun, Principal Ravindra Kumar, community figure Lala Rajkumar, renowned sculptor Devidas Khatri, and cultural coordinator Dinesh Agrawal

Founded in 1990, the Disha Group has carved a notable space in Indian theatre with more than 26 productions staged across the country. For this studio initiative, Dr. Satya Prakash (Secretary) and Sampa Mandal (Theatre Director) played a pivotal role in shaping the vision and the event. Dr. Prakash described the studio as a free, open creative space where young artists can rehearse, experiment, and grow without any financial barriers. Significant contributions were also made by members Sandhya Verma, Neelima Verma, and Varuna Verma, whose dedication strengthened the foundation of this cultural endeavour.

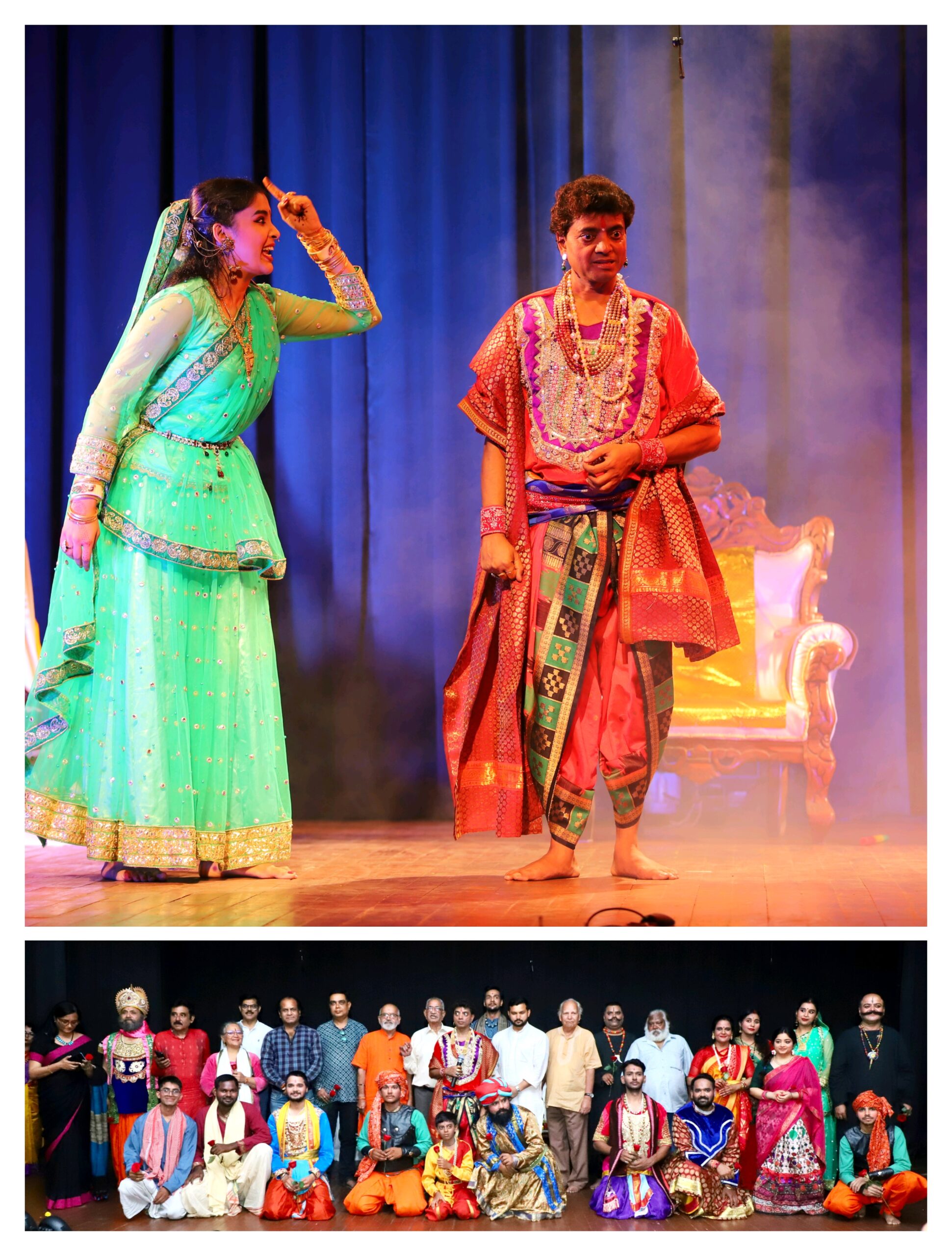

Following the inauguration, AAOMA – The Third Space Foundation presented two plays based on the writings of Daya Prakash Sinha. The first, “Naak Ka Sawal,” a sharp humorous satire, kept the audience thoroughly engaged. Ankit Chaudhary (Thakur), Udit Koli (Pandey ji), and Shreerag M.S. (Kunwar) delivered lively and well-timed performances that evoked continuous laughter. The second play, “Purane Chawal,” unfolded with emotional depth and sincerity. Shikha Arya (Chadmilal), Gagan Chaudhary (Ranjit), Kishlay Raj (Dheer), and Mohammad Siraj (Harish) portrayed the inner conflicts of their characters with remarkable nuance and sensitivity.

Behind the scenes, technical support by Aditya Mukul (Music/Lights), Kashish (Costume/Makeup), and Vipin Kumar & Mohan Koli (Camera) ensured a seamless theatrical experience. Both plays were directed by Meeta Mishra, whose thoughtful staging and rhythmic pacing elevated the aesthetic appeal even with minimal resources.

The next day offered a moment of pure artistic resonance through the Odissi presentation of Tiara Tripathi, who performed a soulful tribute to the late Daya Prakash Sinha. Trained under the acclaimed Guru Madhavi Mudgal since the age of five, Tiara has immersed herself in the Odissi tradition for over 15 years, performing at prestigious festivals including the Youth Festival and Konark Festival, and at institutions such as Sangeet Natak Akademi and National School of Drama.

Her chosen piece, “Khela Lola,” an Oriya champu from Kishora Chandranand Champu, brought forward the subtle charm of Radha being teased by her friend for desiring the unattainable. The choreography — shaped by legends like Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra and Madhavi Mudgal — allowed Tiara to display both expressive finesse and technical mastery. Her command over abhinaya, clean geometry of movement, and serene stage presence created a performance that was at once evocative and deeply poetic.

Holding both BA and MA degrees in Dance and awarded the Scholarship for Young Artists, Tiara’s artistic journey now extends into the intersection of dance and mental health. As the founder of the Mudrika Art Foundation, she continues to nurture interdisciplinary collaborations in contemporary, Odissi, semi-classical movement, and therapeutic arts. Her presentation stood as one of the evening’s most memorable highlights — a luminous blend of devotion, skill, and artistic maturity.

The ceremony was smoothly anchored by Praveen Kumar Bharti, while the organisational support of Harish Tiwari (President), Madhulika Singh (Vice-President), Kewal Krishna Bhatia (Vice-President), and Surendra Verma (Treasurer) ensured a highly successful event.

The inauguration of the Padmashri Daya Prakash Sinha Theatre & Art Culture Studio emerges as a meaningful cultural milestone — honouring a towering figure of Indian theatre while opening new pathways for training, experimentation, and innovation. It marks the arrival of a vibrant creative hub, offering young performers a dedicated space to learn, explore, and contribute to Delhi’s ever-evolving theatrical landscape.