T H E U N F I N I S H E D S A G A

A Love Story

By

Reshma

A shiver ran down my spine as I thought of the evening ahead. My nerves were over-wrought, I was flicking the menu without anything making sense, I’d looked at my watch an endless number of times, and I’d just lit my sixth Marlboro. I was nervous. These were turning out to be the longest fifteen minutes of my life. A waiter materialized as soon as I replaced the menu, and if my behavior surprised him, his training prevented him from revealing it. My blank look prompted a one-sided discussion on aperitifs, and he certainly looked relieved when I settled for a dry martini.

She’d said eight, and it was still only ten-to, but rather than pace restlessly in my penthouse, I’d chosen to be amongst people. And therefore shown up a full half-hour earlier. The drink, when it arrived, helped, and as I allowed the soft strains of music to take over and penetrate my being, I found myself relaxing a little. And it was in this partly euphoric state that I spotted her at the entrance.

She hadn’t changed at all – there was no mistaking the statuesque figure – the same proud carriage, head held high, chin up – she might have been conducting a demo at some finishing school. My heart did a quick somersault at the nostalgic sight, and threatened to leap right out. I rose jerkily.

How did one greet someone after all of twenty-six years, I wondered, as she reached me in measured strides. I made a tentative move to offer my hand, changed my mind, and stood there variously shaping my lips without producing any sound. All those carefully rehearsed opening lines deserted me as I shuffled on my two left feet.

“Time seems to have treated you well!” She eased my discomfiture with an understanding smile. No, even I hadn’t changed at all, and least of all, in my responses towards her. I may have traversed from a gauche teenager to a questionably mature 48-year old, but she still retained the ability to tie me up in knots; and hold all the threads.

I returned a wan smile. “But as always, time saved its best for you! You look absolutely wonderful!”

And I wasn’t exaggerating. In fact, I couldn’t help feeling a trifle disappointed. Her appearance had somehow upset me. I hated to acknowledge it, but deep within me had been lurking a hope that she too would have been unable to find happiness without me. But her serenity, her radiant, dignified demeanor threw me completely off gear. I aborted any ideas I might have entertained of raking up the past, or at least posing as the poor-old-martyr. Even though it was true, why hold her to an emotional ransom when she seemed to be doing so well in life. Going through the motions of ordering drinks and dinner and keeping up a polite conversation wasn’t easy, but I did it. Both her children, it turned out, were long settled, and it was for her elder daughter, who had recently delivered a baby boy, that she was visiting New York. The irony of fate… if only her parents had shared her broad-mindedness about marrying their daughter to an immigrant… if only…

“Hello Jayant, this is Neelima! Remember me? I am visiting your city. Want to meet me at Florentine’s on Friday night at eight? I’ll be waiting.”

Not remember her! I must have played back that precise message on my answering machine dozens of times… Her voice had jolted me right out of my comfortable existence, to take me back to another lifetime. Almost.

“Huh, did you say something?” I suddenly returned to the present. “Snap out of it man, I say!”

of her marriage to an army-man, and from then on I’d left her alone, never attempting to unearth anything more about her.

“I’m really very happy for you.” I did manage to snap out of it completely, and finally heaved a sigh of immense relief – as if a heavy load had just lifted itself off. All these years, spent, proving myself to the whole world, but most of all, to her, to them – that I was worth it after all… too busy to enter matrimony… waiting… somehow, to discover her remorse when she finally met the suave, successful person that I had turned into… All that, and so much else was washed away, as I stood up, feeling cleansed and light-headed, and shook her hand. There was sincerity and genuineness, as I wished her all the best in life, before finally parting… once again.

* * *

“Dear Jayant, God knows I have no right to come marching back into your life like this – and I wouldn’t, in fact, have even met you, if fate hadn’t intervened in a most opportune manner. But when my daughter’s friends mentioned you, I couldn’t resist the temptation. Calling up during working hours was intentional; I knew you wouldn’t be there and therefore wanted to give you the choice of ignoring my message without any embarrassment.

I would have left you alone if you hadn’t shown up. But then you did. And what had begun out of sheer curiosity gave way to something much deeper once we met, and I realized that you had never married. The evening was spent in banalities, when there was so much more to exchange. If this is destiny giving us one more chance, I do not want to thwart it this time.

Too long have I lived with facades, but not any more. Captain Samant and I realized soon after marriage, what a gigantic mistake it had been. Two nice, but completely incompatible souls trapped together. Till heaven do us part? But I was only twenty, and optimistic, and both children followed in quick succession, supposedly to bolster the relationship. Add to that, the uncertainty of war, the long intervening years of separation, and the hope was kept alive.

But the tumultuous journey from Captain to Colonel was just what it was – a charade to maintain appearances. It was only when Parul got married and Rishabh, too, moved off, having joined the Army, that the masks came crumbling down and I began to experience a severe vacuum. Societal pressures kept me from walking out of that hollow institution, till my grandson provided a temporary respite. And these past eight weeks have brought home to me what I’ve been missing without realizing it – the peace, the quiet, the feeling of being free… incomplete, yes, but nevertheless, free… I know I could never return to him now – knew it, even before I met you, so have no qualms about that.

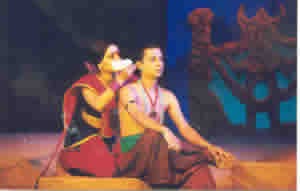

At the recently concluded BHARANGAM, the Theatre Fest organized by the National School of Drama, a Pakistani play,Burqavaganza, produced by Ajoka Theatre Group, was staged at Kamani Auditorium, New Delhi. The play had been banned in Pakistan last year, because of its irreverence to the Burqa, a traditional veil and gown worn by conservative Muslim women. The play is especially relevant and contemporary because the controversy over women covering either their head with a Hijab or also their face and the whole body with a Burqa rages even in the Muslim majority countries which were known for their secular ideals. For example, Hijab, an obligatory code of dress in Islam, was banned in public buildings, universities, schools and government buildings in Muslim-majority Turkey shortly after a 1980 military coup. Prime Minister of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan (whose wife and daughters are veiled) had promised before his first electoral victory in 2002 that the “unfair ban” would be abolished. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP) opposition party have thrashed out a deal on a compromise head-cover to be allowed on campus after decades of an all-out ban. Under the deal agreed to by the two parties, a day earlier, women at universities are permitted to cover their heads by tying the headscarf in the traditional way beneath the chin. While the Turkish PM insists that respect for basic human rights is his sole motivation in pushing through the amendments, some believe that the move would cause immense problems and deal a blow to the separation of state and religion, one of the founding principles of the modern Turkish Republic. Told in a rollickingly funny mode, Burqavaganza laughs at the pointless rigidity of customs and dress code and ridicules the system that upholds their sanctity. The play follows the story of the young lovers: the progress of their romance, the wedding and the birth of the first child. Meantime, the police, looking for the terrorist leader Bin Batin, and the Burqa Brigade who suspect that their Burqas are too colourful and revealing constantly bicker because of their conflicting agendas. An unveiling ceremony follows where the Minister forBurqa Affairs makes a passionate speech about the significance of the Burqa and everyone celebrates with song and dance. The charismatic scholar Hijab Hashmi inspires her devotees to keep their eyes open for the traitors in the Burqa Brigade. Bin Batin carries on his bloody fight against the helmet-covered enemy .The stage action is accompanied by telecast of ‘Burqavision’ programmes which include a soap, a documentary ‘Burqa Though the Ages’, News, Sports, a fashion show and ‘Breaking News’. While Burqas of all shapes and sizes create images and situations reminding the audience of the socio-political situation in Pakistan, two maulanas sitting on the edges of the stage, in a TV show, respond to the questions from their viewers about apparently important questions about interpretation and application of religious teachings. The statements of the maulanas are in fact extracts from ‘Beheshti Zaiver’, a book given to girls at the time of their marriage. Denouncing the ban on the play Madiha Gauhar had then said that the ban was imposed because of pressure from the “burqa brigade”, and that it proved that the government’s enlightened moderation policies were a farce. It was in the early eighties that I had first met Madiha, when I was hanging around with Badal Sircar, Ragini Prakash and Vinod Dua at the Sri Ram Centre Canteen in New Delhi. We were told by Mrs. Acharya, the owner of the canteen, that a Pakistani actress wanted to meet us. We were accosted by this strapping young and beautiful lady who told Badal Sircar that their group had performed his play Juloos (Procession) in Pakistan despite the censorship. A little later, Shahid Nadeem with his Ajoka Theatre Group, performed with our group, Theatre Union, at JNU. Shahid even recorded our play Toba Tek Singh and took it back with him to Pakistan. Set up by a small group of cultural activists in 1983, during General Zia-ul-Haq’s politically and culturally repressive regime, Ajoka has struggled with determination against very heavy odds to produce socially meaningful art. It has addressed vital, sometimes taboo subjects through its hard-hitting and innovative productions. Committed to the ideals of peace and tolerance within Pakistan and in the neighbouring regions, it has frequently collaborated with theatre activists from other countries of South Asia particularly from India, viz. Indian directors such as Badal Sircar, Safdar Hashmi, Anuradha Kapur and Kewal Dhaliwal. Founder-playwright of Ajoka Theatre, Shahid Nadeem, known for his commitment to human rights and peace, is the author of more than 35 original plays and several adaptations. His plays have been performed in Pakistan, India, USA, UK, Norway, Bangladesh, Nepal, Iran and Oman. He is currently the Director of PTV Academy; and Co-director of Panjpaani Indo-Pak Theatre Festival, a festival pioneering interaction between theatre activists of India and Pakistan. He has also worked as Communications Officer of Amnesty International, based in London and Hong Kong. He was awarded Feuchtwanger/Getty fellowship in 2001 and has lectured at various universities in the US. (Sources: Islam Online/NSD/Reuters/ANI) Cast and Credits Play and Direction: Shahid Nadeem * At Stagebuzz.Info if an article is not a review then it is an “Info”Burqavaganza

Burqavaganza – Banned in Pakistan staged in BHARANGAM

A bit of Info* compiled by

Manohar Khushalani

Minister/ Bin Batin/ Chambeli/ Cameraman: Sarfraz Ansari

Maulana 1: Ziafat Arfat

Maulana 2: Imran-ul-Haq

Haseena: Samiya Mumtaz

Khoobroo: Furqaan Majid

Brigade Commander: Khola qurashi

Brigade 1: Asif Japani

Brigade 2: Azaan Malik

Police Officer: Usman Zia

Constable 1: Shahid Zafar

Constable 2: Shehzad

Chorus/ Dancers: Taqoob Masih, Nadeem Abbas, Waseem Luka, Meena

Hijab Hashmi/ Mother: Samina Butt

Guitar Player: Vicky

Sets and Lighting Design: Kewal Dhaliwal

Music: M Aslam

Costume: Zahra Batool

Assistant Director: Malik Aslam

Production Manager: Imran-ul-Haq

Research: Ziafat Arfat

Video recording / editing: Nadeem Mir, Shakeel Siddiqui

The Owl and the Pussy Cat

The Owl and the Pussy Cat

A review

by

Seema Bawa

Actors: Kavita Dang and Kumud Mishra Director: Satyajit Sharma

“The Owl and the pussy cat went to sea in a beautiful pea green boat…”

Thrown together in a low-rent bachelor’s flat instead of a ‘pea-green boat’, the odd couple in this highly amusing Bill Manhoff comedy, is certainly not at sea! ‘The Owl’, Felix played by Kumud Misra, a highly accomplished actor, is a self-styled intellectual author – while ‘the Pussycat’ played by Kanika Dang, is a wannabe actress and model – however, to pay the bills she entertains gentleman callers, a prostitute but not promiscuous.

Having noticed the stream of gentlemen caller at her apartment through his binoculars, the peeping owl does his ‘civic’ duty by informing the superintendent of the building. The pussycat with nowhere to spend the night seeks revenge by imposing on the owl for a bed. And then, through a battle of wits, words, and wisdoms they both start to ‘educate’ each other as well as the audience in ways they never knew they could.

The current production by Dotted Line Productions has wisely kept it simple and has not endeavored to create convoluted and over intellectualized caricatures of the protagonists. The director, Satyajit Sharma, an NSD Alumni with several outstanding acting and directorial performances to his credit, takes two great actors who handle some good old fashioned repartee rather well; coupled with adept handling of a witty script to put together an eminently watchable show.

The play focuses on two people who get to know each other, have sex, and eventually fall in love. As in most romantic comedies, one-liners abound and the protagonists are shown falling from their own self constructed identities. The fight in Felix’s apartment after Doris barges in at the beginning is hilarious. She gets upset by his use of big words, but eventually buys her own guide to extending one’s vocabulary. He is horrified by her “filthy” animal existence exemplified in his use of words like gutter slime and filth for her, but delights in the new experiences she has to offer. The two show each other new ways of looking at things and which is why Doris and Felix’s chemistry works for the audience. It’s is akin to what happens in real life. Their romance is played for laughs, but it’s also sweet and touching. Felix, like most men, has to have a near nervous breakdown before deciding Doris is the one for him through a bitter-sweet dream sequence that evokes meta-theatre. As each displays their softer selves, the audience realizes they have more in common than they think. The two are in transition; looking for that obscure goal of success; he in writing, she in acting. This shared ground draws them together and reflects to the audience a very real struggle that we all experience in relationships.

Odd couples, whether of the same or different sexes have been a comedy formula for decades. The play enthralls with its at times salty language. Most importantly, Kumud and Kanika have a very definite chemistry. Though Kanika’s is better delineated and in intrinsically is the more outrageous and attractive character (being the underdog) in the script, it does not steal the focus. Kumud interprets the inherent wimpy-ness and prissyness of the character with a paradoxical male strength and libido. This makes for a powerful performance that converts the essentially mono-dimensionality of the character into a rather complex and conflicted one. The interlude when the wimpy Felix transforms briefly to a randy ‘baby’ is remarkably executed with Kumud performing from each pore of his being. Kanika has put in a lot of effort into building her character but while she is able to bring to fore the tartness of Doris, the vulnerability written into the character does not come out as well as it may have. Though this prostitute has a heart and it shows. While the play per se is not deep enough to allow for great acting, it does give scope to the two protagonists to demonstrate impressive technical finesse; the director who is apparently debuting for the group needs to be complemented for this.

In order to be memorable theater, the discovery by Felix and Doris that they are good for each other need not be revelatory in the vein of a metaphysical revelation, but should be funny. The director and his cast achieve this with ease. The humor in “The Owl and The Pussycat,” depends largely on sarcasm, insult and the sort of logic that has Doris announce: “I may be a prostitute, but I’m not promiscuous.” A lot of the humor of the play depends on language and the “play” thereon. Much is made of the fact that Doris doesn’t understand words like despicable, aesthetic, assimilate and intrinsic while Felix who seeks to define himself through words or concepts finds them completely incapable of addressing his feelings for Doris. A comedy based largely on language and timing is always a difficult ask and the current production delivers in aces.

Directorial skill is amply demonstrated in terms of technique, stage craft and spatial usage. The fundamentals of good stagecraft such as blocking, body language and use of space have a refreshing rehearsed certainty and professionalism fast disappearing from current productions. Interludes of well chosen music pieces and the intermittent use of gaps during the play deserve to be commended. This despite the somewhat inadequate lighting arrangement around the proscenium of the LTG auditorium

The Owl and the Pussy Cat

The Owl and the Pussy Cat

A review

by

Seema Bawa

“The Owl and the pussy cat went to sea in a beautiful pea green boat…”

Thrown together in a low-rent bachelor’s flat instead of a ‘pea-green boat’, the odd couple in this highly amusing Bill Manhoff comedy, is certainly not at sea! ‘The Owl’, Felix played by Kumud Misra, a highly accomplished actor, is a self-styled intellectual author – while ‘the Pussycat’ played by Kanika Dang, is a wannabe actress and model – however, to pay the bills she entertains gentleman callers, a prostitute but not promiscuous.

Having noticed the stream of gentlemen caller at her apartment through his binoculars, the peeping owl does his ‘civic’ duty by informing the superintendent of the building. The pussycat with nowhere to spend the night seeks revenge by imposing on the owl for a bed. And then, through a battle of wits, words, and wisdoms they both start to ‘educate’ each other as well as the audience in ways they never knew they could.

The current production by Dotted Line Productions has wisely kept it simple and has not endeavored to create convoluted and over intellectualized caricatures of the protagonists. The director, Satyajit Sharma, an NSD Alumni with several outstanding acting and directorial performances to his credit, takes two great actors who handle some good old fashioned repartee rather well; coupled with adept handling of a witty script to put together an eminently watchable show.

The play focuses on two people who get to know each other, have sex, and eventually fall in love. As in most romantic comedies, one-liners abound and the protagonists are shown falling from their own self constructed identities. The fight in Felix’s apartment after Doris barges in at the beginning is hilarious. She gets upset by his use of big words, but eventually buys her own guide to extending one’s vocabulary. He is horrified by her “filthy” animal existence exemplified in his use of words like gutter slime and filth for her, but delights in the new experiences she has to offer. The two show each other new ways of looking at things and which is why Doris and Felix’s chemistry works for the audience. It’s is akin to what happens in real life. Their romance is played for laughs, but it’s also sweet and touching. Felix, like most men, has to have a near nervous breakdown before deciding Doris is the one for him through a bitter-sweet dream sequence that evokes meta-theatre. As each displays their softer selves, the audience realizes they have more in common than they think. The two are in transition; looking for that obscure goal of success; he in writing, she in acting. This shared ground draws them together and reflects to the audience a very real struggle that we all experience in relationships.

Odd couples, whether of the same or different sexes have been a comedy formula for decades. The play enthralls with its at times salty language. Most importantly, Kumud and Kanika have a very definite chemistry. Though Kanika’s is better delineated and in intrinsically is the more outrageous and attractive character (being the underdog) in the script, it does not steal the focus. Kumud interprets the inherent wimpy-ness and prissyness of the character with a paradoxical male strength and libido. This makes for a powerful performance that converts the essentially mono-dimensionality of the character into a rather complex and conflicted one. The interlude when the wimpy Felix transforms briefly to a randy ‘baby’ is remarkably executed with Kumud performing from each pore of his being. Kanika has put in a lot of effort into building her character but while she is able to bring to fore the tartness of Doris, the vulnerability written into the character does not come out as well as it may have. Though this prostitute has a heart and it shows. While the play per se is not deep enough to allow for great acting, it does give scope to the two protagonists to demonstrate impressive technical finesse; the director who is apparently debuting for the group needs to be complemented for this.

In order to be memorable theater, the discovery by Felix and Doris that they are good for each other need not be revelatory in the vein of a metaphysical revelation, but should be funny. The director and his cast achieve this with ease. The humor in “The Owl and The Pussycat,” depends largely on sarcasm, insult and the sort of logic that has Doris announce: “I may be a prostitute, but I’m not promiscuous.” A lot of the humor of the play depends on language and the “play” thereon. Much is made of the fact that Doris doesn’t understand words like despicable, aesthetic, assimilate and intrinsic while Felix who seeks to define himself through words or concepts finds them completely incapable of addressing his feelings for Doris. A comedy based largely on language and timing is always a difficult ask and the current production delivers in aces.

Directorial skill is amply demonstrated in terms of technique, stage craft and spatial usage. The fundamentals of good stagecraft such as blocking, body language and use of space have a refreshing rehearsed certainty and professionalism fast disappearing from current productions. Interludes of well chosen music pieces and the intermittent use of gaps during the play deserve to be commended. This despite the somewhat inadequate lighting arrangement around the proscenium of the LTG auditorium

Pulling Strings

Pulling Strings

A review of the Ishara International Puppet Theatre Festival

by

Divya Raina

It doesn’t quite matter whether one pulls strings or uses larger than life marionettes, glove or rod puppets, its pure theatre that one is watching. Quite distinct from a puppet or the kathputli show this form of theatre is as creative, compelling and meant for adult audiences as much as for kids. In fact Dadi Pudumjee has been a staunch crusader for the cause and promotion of puppet theatre for decades now. An extraordinarily talented puppet creator and manipulator, director, performer and choreographer, he along with his remarkably versatile crew of the Isharapuppet theatre troupe, has entertained and enabled Indian (and international) audiences to view a totally different type of performance art.

This was vividly brought out at the staging of the Spanish “Batuta” or small baton, at the recent Ishara International Puppet theatre Festival held at the India Habitat Centre in collaboration with ICCR and others. It was quite a treat to watch the interplay of music, lighting, spoken dialogue and most of all, the entrancing moves and gestures of the animated puppets of different shapes and sizes.

What came through clearly was the constant refrain” I love music” and also “musica classica”, and the entire duration of the performance was devoted to an exploration of different forms of music with accompanying puppet movement. The saxophone puppet duet was the highlight with its foot –tapping rhythm, but there were many other musical elements incorporated. It was as though there was an earnest plea in this globalised TV-corrupted world, to both young and old viewers to re-connect with “purer” forms of music than the fusion and confusion of mtv-inspired forms one generally finds today.

Did it work? For most of the audience, with its short- attention -span habits and general restlessness it was quite a novel experience. One wishes however that anxious moms insisting on ramming ‘culture’ down their offspring’s throats would dispense with their loud running commentaries which unfortunately become an unwelcome sound-track thrust upon one on such occasions.

Vasant Utsav in Vasant Vihar

Vasant Utsav in Vasant Vihar

Info on the Indian Spring Show

by

Divya Raina

Winter never fails to turn to spring. Even though Delihites experienced a longer and severer winter this year, residents of Vasant Vihar were spotted bundled up in their warmest at their neighborhood “Vasant Utsav 2008”; a cultural pot pourri of music, dance, poetry, traditional craft and much more. Visitors included foreigners, diplomats and many others who were not necessarily residents but got to discover and sample various cultural events and cuisines virtually at their doorstep! A couple from Denmark was seen tucking into their first taste of masala dosa and thrilled to find they did not have to travel far for it.

What elevated this “colony” show of performances from the usual run of the mill melas however was to ensure that only the best was offered .The Sunday sarod concert was by none other than the talented duo;Amaan and Ayaan Ali Khan. There was in fact a virtual roll call of celebrity names in attendance. The festival was inaugurated by Shiela Dikshit and on Sunday Tejendra Khanna was the special guest.Raghavendra Rathore, Ritu Nanda, Harmala Gupta were roped in for various events as were Roshan Seth,Suhel Seth, Feroze Gujral,Ajay Judeja to mention a few.

Apart from the vibrant Bhangra,Gidda and more folk dances from Orissa and Manipur, Kathak and Qawwali were the Dastkaar stalls selling ethnic ware and exquisite and unusual handlooms and handicrafts, including some astonishing crocodile chairs! What , to me was the highpoint of the entire show, however was the opportunity to view some very fine works of art from masters like M.F.Hussain, Ganesh Pyne, Nalini Malani,as well as quite fine pieces from local residents. And overseeing all events was Romesh Chopra,the President of the Vasant Vihar Welfare Association ,the chief organizer working in partnership with the Sahitya Kala Parishad.

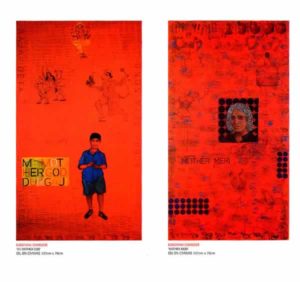

Kanchan Chander: A Woman Artist of Vision

Kanchan Chander: A Woman Artist of Vision

by

Seema Bawa

While most art is influenced by the personal history of its creator, Kanchan Chander’s paintings are her personal history; from student to artist to hopefully married and then joyful mother to estranged wife and then a single mother. The three decades of her paintings reflect and reinforce these states, and are emotively and expressively explored through her art which is not only visual but experiential.

In her early sketches, the impact of a brother’s death on her and her family are delved into. In Drifting Apart two female figures, her mother and she, cling to one another in shared grief while the male figure, the father, stands alone masking his sorrow.

The angst emerges again in her etching Expression II, a feminine interpretation of Edward Munch’s Scream. The contorted female face with a wide gaping mouth from which a silent eternal scream seems to be emerging is a very powerful image that is a testimony to Kanchan’s early potential.

In the first decade of her artistic journey she concentrated on print making especially etchings, lithographs and woodcuts. It is in the latter she uses bold, almost rough strokes to match the thematic of primitive primordial relationships and identities. Using archetypes from African and Polynesian tribes, she has posed a couple where the female figure stands with her legs crossed while the man stands in a hieratic pose, neither looking at each other, emphasizing an estrangement despite the intimacy of nudity.

During the period of her estrangement from her husband she painted on window, frames doors and furniture, which came out from her parental house (which was being rebuild) where she had to move in. As if painting on the dismembered utensils of her life and through this process reassembling her “self” under a dramatic new aegis.

Her signature work that emerge out of her re-assertive new female “self” are voluptuous female torsos. Sensual, confident and centered these are projected in bright feminine colors such as pink orange royal blue. Over a period of time she has experimented with ornamenting the torsos with so called feminine accessories such as sequins, beads, gold and silver foil; unapologetically emphasizing and celebrating the ornamental, alamkara and also the physicality associated with womanhood. In contrast the relatively later male torso, Male/Nail are superimposed with symbols of masculine power and violence such as hammers, saws, scissors and knives.

Simultaneously she used the iconic symbolism of Indian Goddesses in her paintings such as Durga and Me in which she has juxtaposed the three eyed dark Goddess, with a red tongue hanging out seated on a stylized lion, with various profane motifs of masculinity.

During the next period came her series, Pallav’s world, which she painted with mixed media on takhtis representing the child’s world of school, play and homework. The use of motifs such as alphabets, kitschy popular heroes and boyhood ideals such as the cartoon character of He Man, emphasize the environment in which the mother and child dwell.

In her recent works two thematic trends are obvious. The first continues from her earlier Vatsalya series through which she had expressed the bonding between the single mother and child; now the roles seem reversed in What’s your POA, MAA where the child standing behind her seated self portrayal seems a young adult, protecting her. The second trend is a more settled, peaceful portrayal of flowers and Buddha’s head, with of course some hint of disturbance, with an overall coming to terms with life, desire and expectations.

The show significantly highlights the works of a woman-artist who is comfortable and indeed assertive of this dual identity. Though she and indeed her work are not radically feminist with a rejection of all that is male or seeking to glorify only the female, there is a refreshing and unapologetic delving into feminine, domestic and maternal concerns and sensibilities in her art.

STAGEBUZZ presents Dilip Hiro’s play about Taj Mahal, Palace Romances and Intrigues

To ANCHOR A CLOUD

Dilip Hiro’s play about Taj Mahal, Palace Romance and Intrigues

Stagebuzz in association with Pierrot’s Troupe presented a reading of a historical play To Anchor a Cloud by the Internationally acclaimed Historian and Journalist Dilip Hiro. The Play was directed by Manohar Khushalani. The Cast Included S. Somasunderam, Manish Manoja, Mala Kumar, Joya John and Sanyam. The 1st reading / enactment was performed at Alliance Francaise on 28th Feb and the next public reading was at Akshara Theatre on 2nd March. The play received rave notice in the press (For details click the (Press) button in the menu row. The story is about the intensely complex romantic relationship between Shahjahan and Mumtaz Mahal and the power struggle for the throne of the Mughal Empire after the death of Empror Jehangir. Amongst the many plots and subplots the play also examines Shahjahan as the Architect builder and Mumtaz Mahal as the brain behind Shahjahan. Dilip Hiro is in India to promote his latest Book Blood of The Earth: The Global Battle For Vanishing Oil Resources, published by Penguin India. During his lectures he has often quizzed his audience about what they know about Mumtaz Mahal. Most people don’t know much beyond the fact that she was a ravishing beauty and that she died in child birth . Dilip has fleshed out the personality of Mumtaz Mahal about whom nothing much has been written in History.

Dilip Hiro was born in the Indian subcontinent, and educated in India, Britain and the United States, where he received a Master’s degree. He then settled in Britain in the mid-1960s, and became a full-time writer, journalist and broadcaster. He has published 30 books and contributed to 16 more.

He has written extensively for stage, television and cinema. To Anchor a Cloud, his three-act stage play about the struggle for power by Mumtaz Mahal and Shah Jahan, and the concept of the Taj Mahal, was produced in London in 1970, starring Saeed Jaffrey, Jamila Massey and Mrac Zuber. It was published in 1987 as part of Three Plays. The other plays in the collection wereApply, Apply, No Reply, written originally for BBC TV and broadcast in 1976, and A Clean Break, a one-act play performed in 1978. He scripted 10 of the 21 episodes on the BBC TV’s drama serial Parosi, centered round the lives of South Asian immigrants in Britain, broadcast in 1978-79 and repeated a year later. He is the co-script writer of A Private Enterprise, a story of a young Indian immigrant in Britain trying to become a successful businessman, which was judged the best British film of 1974, and won prize at the Chicago Film Festival. .In 1985 he wrote The Video Wicked, a stage play for the Royal Cur Theatre, London, for young audience. The Asian Cooperative Theatre, London, presented a staged reading of his three-act play, In Search of Lord Clive’s Corpse in 1993.

As the play, To Anchor a Cloud, is set in the seventeenth century India a brief description of the Moghul dynasty, which then ruled the country, should help understand and appreciate it better. Jahangir was the Emperor of India from 1605 to 1627. He had four sons ‑ Khusru, Parwez, Khurram and Shahriyar ‑ in that order. Shah Jahan (literally, ‘Ruler of the World’) is the name that Prince Khurram acquired when he finally won the imperial throne. However, for the sake of simplicity, the authorI has used the name Shah Jahan throughout the script. Since the Moghul dynasty lacked the tradition of the eldest son automatically succeeding the father, rivalry for the throne broke out during the ruling emperor’s lifetime. This happened in the case of Jahangir and his sons. In 1618, when the play opens, the fight for the imperial throne was already on.

“The main outline of the play is faithful to history. But to make drama out of history a playwright has to distort and recast some facts and events, and invent others, and, says the author, “I have done so.”

Regarding the main characters, Dilip has visualised them thus:

Jahangir: (Manish Manoja). Moody with a quick changing mind; yet shrewdly aware of the interests of his Empire.

Nur Jahan: (Joya John) Favourite wife of Jahangir. Domineering. Given to intrigue in her later days.

Shah Jahan: (Manohar Khushalani / S. Somasundaram).Sensitive, artistic, ambitious. His idealistic approach to life makes him prone to ‘holier‑than‑thou’ attitude. Devoted to Mumtaz Mahal. Fond of poetry, music and architecture; but also a valiant soldier.

Mumtaz Mahal: (Mala Kumar / Joya John) Favourite wife of Shah Jahan. Devoted to her husband without being servile or overbearing.

Asaf Khan:(Manish Manoja) Father of Mumtaz Mahal, brother of Nur Jahan. Flexible except in his unswerving loyalty to Mumtaz Mahal, and thus to Shah Jahan.

Parwez: (S. Somasundaram / Manohar Khushalani). Stout with a bland, clean‑shaven face. Slow in his movement and wits; but has zest for enjoyment.

Rodreguiz: (Sanyam) A Jesuit priest. Wily, with a special flair for striking bargains. Always dressed in black

India Dominates MIFF, Wins Largest Number Of Awards In International Category

by

B B Nagpal

Senior Film Critic

Makers of short or documentary films generally feel they are given the short shrift when they try to find finances for making their films, and are then treated to a step-son treatment by the government, the public service broadcaster Doordarshan, and the private television channels as far as distribution and exhibition goes. As a result, it is felt that people are no longer interested in short, documentary or animation films.

But the large number of viewers that turned up at the Tenth Mumbai International Film Festival for Documentary, Short and Animation Films were enough to prove that the medium has its own niche viewership. And the ovation that the award-winners got also showed that their judgment did not differ very much from that of the juries.

However, though every festival has some good and some bad films, the primary problem with MIFF is that the duration is just one week thus permitting only one show per film, and the number of films and variety of sections needs to be curtailed. The press conferences also could have been coordinated in a better manner since they often clashed with the film shows.

It was also necessary that while there are films that last less than a minute and others may go over one hour, the selection of films in one slot should as far as possible be of a similar kind. For example, all films dealing with wild life or all those made in animation could have been shown together. This helps the discerning viewer to decide the kind of films he or she wants to see, since all four theatres were showing different films and making a choice was often difficult.

The festival, which is held every second year by the Films Division (a media unit of the Union Information and Broadcasting Ministry) in collaboration with the government of Maharashtra and the Indian Documentary Producers Association, took place in the four theatres of the National Centre for the Performing Arts at Nariman Point in Mumbai from February 3 to 9.

A total of 235 films were shown in the special packages in the festival. In addition, there were 44 films in the International Competition from 16 countries, 54 films in the Indian competition, and 13 international and nine Indian films in special screenings. Films from a total of 37 countries were screened in different sections.

Renowned Manipur filmmaker Aribam Syam Sharma received the V Shantaram Award for Lifetime Contribution from Kiran Shantaram amidst a standing ovation. The award carries a shawl, a citation, and a cash component of Rs 2,50,000.

Sharma is a film director, actor, critic, and music director. He came to limelight with his award winning film ‘Imagi Ningthem’ (My son, My Precious) that received the grand Prix at International Film festival at Nantes in France in 1982. His other acclaimed films include ‘Ishanou’, the official selection (un Certain Regard) for Cannes Film Festival 1991, and ‘Sangai-The Dancing Deer of Manipur’ declared as the “Outstanding Film of the Year 1989” by the British Film Institute. He has directed nine Manipuri feature films and 26 non feature films. They include ‘Sanabi’ (The Frey mare) in 1996, ‘Rajarshee Bhagyachandra of Manipur’, and ‘Gurumayum Nirmal’. He has won numerous national awards and also chaired many juries.

Indian films bagged the top award – the Golden Conch – for best documentary in both the national and international categories even as it bagged four other awards in the international category at the Festival.

While ‘India Untouched – Stories of a People Apart’ by Stalin K. based on the oppressive caste system got the top award in the Indian section (Rs 1,50,000), ‘Goddesses’ by Leena Manimekalai on women’s emancipation received the Golden Conch in the international section (Rs 2,50,000) for films up to sixty minutes.

‘India Untouched’ also won the award of Rs 100,000 for best film/video of the Festival for the Producer Drishti – Media, Arts and Human Rights.

In ‘Goddesses’, the young filmmaker tells the story of three old material goddesses who for different reasons find themselves naturally emancipated from Tamil tradition and orthodoxy. Leena creates a trusting filming arena that was never manipulative so that the three women opened up and revealed their total strength and power bordering on the archetype. They emerged free, master of the very tradition that had earlier kept them shackled.

‘India Untouched-Stories of a People’ not only achieves the ideals of socially and politically committed documentary film making, but unflinchingly uncovers the all pervasive, deeply rooted and still existing caste system in twenty first century India, with chilling evidence that it shows no sign of abating in generations to come. In fact, the Jury recommended the film as essential viewing for all audiences worldwide, adding that the film is in the best tradition of documentary film making and is an inspiration to all filmmakers for independent, thought-provoking, free-spirited use of the medium for social change.

The film’s producer Drishti – Media Arts & Human Rights won the award for taking the initiative and having the courage to investigate the issue of untouchability and its ramifications in all corners of Indian society.

The awards were given away on 9 February in Tata Theatre by Festival Director and Films Division Chief Producer Kuldeep Sinha, filmmakers Shyam Benegal and Jahnu Barua, and actress Nandita Das in a ceremony conducted by television actress and presenter Rajeshwari Sachdev.

The other Indian films to win awards in the international category were: ‘Kramasha’ by Amit Dutta which won the best fiction up to 75 minutes (Golden Conch and Rs 2,50,000) and the Producer’s Award for the Film and Television Institute of India (Rs 100,000), ‘Ink’ which was the first best film by director Bharani Thanikella (Trophy and Rs 100,000), and ‘Undertakers’ by Emannuel Quindo Palo which shared the award for second best fiction film up to 75 minutes with Belgium’s ‘Bare Handed’ by Thierry Knauff (Silver Conch and Rs 100,000).

In ‘Kramasha’, the music keeps one quietly enthralled with a resonating sense of things without a need to necessarily reduce the experience to a verbalization of meanings. The film shows a world of images and sounds that make one smell and touch the lush of nature amid a mysterious index of hallucinations. Like a dream that one may fail to understand but that reaches deep recesses of the unconscious and touches familiar chords, this film by Amit Dutta weaves a powerful narrative that blends legends, myths and nostalgia into a film that allows us to recall one’s early experiences.

Emannuel Quindo Palo’s ‘Undertakers’ manages to distance the viewer from the narrative and create a moving account of a Catholic coffin maker whose business is death but whose dead friends can claim free coffins. The absurd idiom of the film draws a humane picture of the struggles of an ordinary salesman who appears strangely caught between his survival and personal ethic.

Through surreal imagery, Bharani’s ‘Ink’ was able to employ a violent visual idiom for existential struggle of the poet, and the fight he wages against violence of terrorism. In this film which is full of resilience, the poet’s wife deeply worried about their lives takes on the mantle of fight against terrorism after the poet’s death.

Just the manner in which the dancer in Knauff’s ‘Bare Handed’ handles the newspaper and the noise caused by it to strangely reveal the violence a newspaper and therefore the world around us may carry. But it is the dancing woman whom a verbal world threatens to contain. In a series of deft choreographed movements and an equal graphic light the film makes the dancer dance her way through memories and desires until after a complete immersion in this world she loses herself in it.

Poland, the United States, and Egypt won two awards each in the international section. Two Polish films ‘One day in People’s Poland’ by Maciej J. Drygas and ‘Beyond the Wall’ by Vita Zelakeviciute, both produced by Drygas, shared the award for Second Best Documentary up to sixty minutes duration (Silver Conch and Rs 100,000). ‘Salata Baladi’ (House Salad) by Nadia Kamel of Egypt got the Golden Conch and Rs 2,50,000 for best documentary above 60 minutes and the international critics FIPRESCI award (Certificate of Merit). The two American films to win awards were ‘Flow: for love of water’ by Irena Salina got the FIPRESCI award and Rs 100,000, and ‘View from a Grain of Sand’ by Meena Nanji which won the second best documentary film above sixty minutes (Silver Conch and Rs 100,000).

September 27, 1962 was an ordinary day in Poland except for its reconstruction by Drygas in the film ‘One Day in People’s Poland’. The archival images and sounds retrieved from several sources obviously do not synchronize to a singular reality. Without an effort to force a historical realism upon the material, the director keeps the two tracks independent, making them move closer and further away from each other, creating an extraordinary document that is startling in its revelation of the nature of surveillance the state maintained in the sixties by keeping account of banal and inconsequential details in the daily life of its suspect citizens. The enormous task of editing the monumental archival material has been handled very competently.

‘Beyond the Wall’ uses short and pure images that elude description. Through this poetic procedure, the director directly enters into a hazy universe of Russian soldiers sent to prison hospital to serve their sentence. The nondescript events such as the walks, the meals, the medicines, the crowding of the cell generate an unforgettable poem of silence and depth in confinement. Vita Zelakeviciute’s narrative of broken spirits is a reflection on cold and heartless systems mankind is able to set in place in governance of countries.

‘Salate Baladi’ breaks down the classical cinema composition and makes a film deeply insightful of history. It makes geographical borders between countries appear unnatural, incapable of constricting families from their extensive affinities. The metaphor is no longer the family tree rooted in local soil – it is closer to a multiplicity in the manner the grass grows.

Faced with an environment where women are oppressed to the extreme, Meena was able to make her characters in ‘View from a Grain of Sand’ feel safe for them to candidly re-evaluate their condition under the Taliban and post-Taliban periods in Afghanistan. Even as they put themselves to risk they are prepared to boldly share their knowledge and experience with the filmmaker.

The FIPRESCI jury decided to characterize its Award as recognition of films that bring unknown shocking revelations that threaten ecological and even existential balance of planet Earth. The depiction of a global crisis caused by privatization of natural resource such as water in the film ‘Flow: Love of Water’ attempts to educate the audience of atrocities major corporations commit against individuals, families and communities in the name of water and for the sake of plain old profit. The message of the film is clear: make water free, clean and available to the citizens of the world. The revealing research Salina conducted was exemplary.

In the Indian section, the Golden Conch and Rs 1,50,000 also went to best fiction ‘Manjha’ by Rahi Anil Barve who also got the award for best first film of a director (Rs Trophy and Rs 25,000), and best animation film ‘Myths about you’ by Nandita Jain. Other awards included Indian Jury Award (Rs 100,000) which went to two films: ‘I’m very beautiful’ by Shyamal Kumar Karmakar and ‘Thousand Days and a Dream’ by P Baburaj and C Saratchandran, the Indian Critics award to ‘Mahua Memoirs’ by Vinod Raja which also received the award for second best documentary (Silver Conch and Rs 75,000).

‘Mahua Memoirs’ compassionately exposes the ruthless underside of corporate globalization through the ongoing decimation of Adivasi lands, people and their cultures throughout India. Crafted with outstanding visuals and haunting music, it is an urgent call to re-examine the policies of the day.

In ‘Manjha’, the first-time director Rahi Anil Barve’s fictional expression of child sexual abuse and survival has been portrayed in a highly individualistic, graphic and cinematic style. The filmmaker manages to extract outstanding performances from the actors within a stark, industrial urban landscape. The film is also laudable for the understanding of cinematic form and idiom and having the courage to push the form to tell a difficult story.

‘Myths About You’ is a clever and imaginative representation of the history of the Universe, both in terms of Hindu mythology and scientific research, in an original graphic style, all within a short span of 9 minutes.

‘I’m the Very Beautiful’ is a personal, complex and often contradictory portrait of an indomitable woman and her continuous struggle in her pursuit of a life of freedom and dignity despite her social stigma in a patriarchal and chauvinistic society. In its style and treatment, the film mirrors the free spirit of the protagonist with abandon and candour.

‘Thousand Days And A Dream’ tells the poignant and dramatic story of the peaceful struggle of common people against a gigantic multinational company supported by the policies of the state in which the people have been deprived of their vital, basic natural resources and livelihood.

The Silver Conch and Rs 75,000 for second best films also went to ‘The Lost Rainbow’ by Dhiraj Meshram produced by FTII (fiction up to 75 minutes) and animation film ‘Three Little Pigs’ by Bhavana Vyas and Akarito Assumi.

‘The Lost Rainbow’ presents a series of nostalgic, touching moments in an evocative and playful manner, enhanced by the realistic performances of the child actors. The film details how the results of mischievous sibling rivalry can haunt the protagonists for the remainder of their lives.

‘Three Little Pigs’ is a well-known childhood story made through wire frame animation techniques in a deceptively simple style. The film has background voice-overs in the form of a conversation recalling the story, which is both engaging and amusing while bridging the documentary form with animation.

Special Mention and Certificate of Merit was awarded to two films: ‘Our Family’ by Dr K P Jayasankar and Dr Anjali Monteiro, and ‘Raga of River Narmada’ by Rajendra Janglay.

‘Our Family’ is a compassionate and sensitive portrayal of the third sex – their bonding and their aspirations. The film traces their roots sourced from mythology combined with a mesmerizing one-person performance of the traumas and stigma experienced by their community.

‘Raga of River Narmada’ has fascinating flowing visuals highlighting the river in its many vibrant moods through its journey complemented by an exceptional use of the Dhrupad.

Apart from the main sections, there were sections like ‘Best of Festivals’ for selected films from some renowned documentary, short and animation film festivals and Oscar winning and nominated films, a retrospective of films by jury members, a section of Classics featuring films of great masters of documentary films which will have films made by Great Masters like Bert Haanstra, Robert J. Flaherty, Francois Truffaut, Istvan Szabo, Kristof Zanussi and Ritwik Ghatak. This package was organized with the support of National Film Archives of India. A Film Memoir showed biographical films made on great filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky, Ingmar Bergman, Satyajit Ray, and Bimal Roy

There was a special and rarely seen section on films on the Second World War with rarest film records of the Indian troops in action at various part of the world during Second World War. This will also feature the battle of Britain, Russia and other major incidents of that period. This package was put together with the help of the Armed Forces Film & Photo Division, Delhi.

There were sections for films from the North East and from Jammu and Kashmir, and Glimpses from the archives of the Division, apart from homage to filmmakers who passed away in the recent past.

Unfortunately, most of the films which won awards are unlikely to be shown anywhere, since Doordarshan shows the films at unearthly late hours and the Government is still not taking a decision on a proposal by the Films Division for a separate documentary channel. The NDTV recently commenced showing documentaries once a week, but all this is hardly enough.

It is high time that the Information and Broadcasting Minister Mr Priyaranjan Dasmunsi loves up to the promise he made on the opening day of MIFF that he would clear any proposal for a documentary channel within five days. With the new advent of short features and amusing animation, even a documentary channel is bound to find sponsors and become commercially viable

Dabbling In Babble

Dabbling In Babble

Keval Arora

Tim Supple’s Production of Shakespeare’s Mid Summer Nights Dream is currently touring India. Keval Arora takes on Supple for his comments (made earlier) on Indian Theatre and multicultural collaboration.

What is it about multilingualism that draws so many theatre practitioners to dabble in it, much like moths being drawn to a flame? And, what is it about multilingualism that makes many of them end up getting burnt by the encounter? Why is it that Tim Supple, who brought to India a perfectly competent production of The Comedy of Errors with the Royal Shakespeare Company some years ago, has ended up this time offering a version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that makes all the right noises but falls woefully short of making sense?

Well, actually, not all these noises were politically correct. . Supple’s comments on intercultural collaboration (carried in the brochure that accompanied the premiere production in 2006) may have been a shade too driven by the enthusiasm of a ‘been-there-seen-that’ cultural traveller, but did he really think he would win friends and influence people by his description of Indian theatre as “less tangible, less modern, less structured than ours and often fashioned with basic design and rough execution”? However, win friends he did, as can be gauged from Ananda Lal’s comments (in that same brochure) about Supple’s work. Says Lal, “Knowing the debates [revolving around issues of ‘neo-colonial exploitation’ in ‘inter-cultural theatre’], observing him direct at close range and having asked members of the team, I can vouch for the fact that he is sensitive to the issue and its dangers. As corroborated by the performers…no appropriation occurred.” (Lal also goes on to claim that Supple as “a foreign director has achieved national integration for Indian theatre before any Indian could”, but I think we could let that pass as an instance of our Indian habit of being hospitable to the point of embarrassing everybody around!) The first statement is by itself a great Certificate of Merit, though it is difficult to fathom the authority with which assurances such as “no appropriation occurred” can ever be offered. Besides, the prospect of a post-colonial watchdog snooping around for evidence of appropriation during rehearsals can hardly be the kind of thing that leads to intercultural bonhomie let alone transparency!

Cordial and collaborative dealings in work processes don’t guarantee that the art thus produced will be free of appropriative relations. Plays aren’t exactly processed on a shop-floor where one presumes hygienic procedures will result in non-contaminated products. Nor are ‘appropriations’ tangible actions that can be detected in the making, like embezzlements or fraud. You can monitor rehearsals all you want on CCTV, interview as many employees (read ‘actors, technicians, etc’) as you like, and still discover outcomes that are suspect in their negotiation of social and cultural identity. In other words, ‘appropriations’ don’t have to be rooted in malicious intent: often, the best-intentioned at heart still end up stepping into shit.

Take, for instance, Supple’s decision to go multilingual when asked by the British Council to create a production in India and Sri Lanka. He writes, “To restrict ourselves to performers who worked in English would be to miss out on a wealth of different ways of making theatre…. It would also be a lie.” How can one not approve of such sensitivity towards our situation in the subcontinent where – and we can speak more freely than Supple feels he can – the best way of making theatre is not to be found in our English language stage. So, his decision to grant performers the comfort of working in their own languages led inevitably to Midsummer being conceived as a multilingual production. Though Lal is right in noting that “in the West, multilingual theatre has become fairly common, particularly in international projects”, it is important to recognise that Supple’s decision to go multilingual has been prompted less by the project’s ‘international’ status than by his wish to make it accessible to the broadest swathe of performers. Not to mention his need to give the Shakespearean text its due: as he says, “whatever else a Shakespeare production might do, it should seek to reflect the time and place in which it is made with vivid honesty.”

Laudable as this may sound, how true is it of Supple’s own work with Midsummer? Does its multilingualism, which lies at the heart of this intercultural project, reflect anything at all, let alone with vivid honesty? Midsummer has several languages – English, Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Malayalam, Tamil and Sinhalese – operate indiscriminately in performance, cropping up and dropping out without evident purpose or necessity. With some characters speaking primarily in one language and others switching between languages for no apparent cause; with no patterns being discernible in the connections drawn between situation, character and the language/s used, Supple’s multilingualism add up to little more than a noble-hearted linguistic egalitarianism.

Egalitarian motivations of this sort can’t take you far, especially if none of these languages is textured as a living, cohabited entity. The idea that languages are grounded in socio-cultural spaces and are imbricated in personal identity, that they shape memories of shared pasts and imagined futures, that they are as much bones of contention as means of contestations — none of these, on the evidence of the performance, seems part of Supple’s plan. His production sails through the melange of tongues without once indicating that the bewildering mix of words and accents amount to anything more than a log of semantic equivalences. As a result, Midsummer’scharacters are reduced to merely speakers of many tongues, and its text flattened to opaque displays of ‘otherness’, which lack even the resonance and difficulty that negotiating the ‘other’ brings in its wake.

Surely, a multilingual theatre has to foreground language as vital to its meaning, else why should any theatre strive to move outside the confines of its single, original language? An advantage with monolingual theatre is that when all characters speak the same tongue, it is possible, as writer Manjula Padmanabhan has averred in relation to her play Harvest, for the language to be divested of social and geographical referents and to that extent become ‘invisible’. (Writers then turn to vocabulary and intonation to bring in the desired social textures.) It is when two languages are made to coexist in the same text that questions arise as to why a character speaks in one and not the other language; questions that need to be answered even more urgently when the same character is seen to shift from one language to another.

Thus, multilingual productions pose issues of naturalness and probability in a deeper vein, and in the process demonstrate their potential to handle richer representations. But for that to happen, their discrete languages need to be tagged for difference and located in a socio-cultural hierarchy, in the same manner as these operate off-stage. If, as in Midsummer, the various languages on show are offered in a non-problematised, unified terrain, then I’m afraid this ends up as an aestheticised unity of the most banal kind.

Moreover, there seems to be some confusion here. Sure, Indian theatre is multilingual, as Supple claims — but only to the extent that India, by virtue of being a multilingual nation, has theatres in many languages. Texts, however, continue to be written and played mainly in a single language (including regional variations and dialects does not a multilingual theatre make!). Few theatre pieces shoulder on their back a hold-all of many languages for the simple reason that audiences aren’t multilingual – at any rate, not in the broad range that Midsummer imagines. How does a multilingual theatre work then for audiences when its text is segmented into distinct clumps of speech which are alternatingly inaccessible to spectators (as they surely also were to the other actors on stage)? It’s ironical that Supple’s inclusivist gesture towards the individual actor ends up as an exclusionary experience for his spectators.

Not that the production is scrupulously caring about its actors either. For a project that kicked off with a view to enabling the non-English speaking performer, it is strange to see almost every actor in Midsummer speak in English at some point, regardless of that actor’s comfort with the language. I have no clue as to why this happened or what it is meant to achieve. All I do know is that the thick, regional intonation of English speech in such cases showed up speakers in a poor light, and left one silently willing the actor to retreat into the comfort zone of his native tongue!

As for the claim that multilingual theatre is the theatre of the future, let me point out two small cheat codes embedded in the zone of the multilingual. One, most multilingual theatre tends to remain closeted with the classics. In other words, with such plays where spectators’ familiarity with the text functions like an insurance policy because it neutralises the risk of incomprehensibility that is inevitable when languages are used in a manner that makes them only selectively comprehensible to audiences. Two, most multilingual theatres tend to favour designs that have strong visual components and a physicalised performance style as staple features of its performance grammar, as if this is one way of working around the fact that large portions of the text may remain unintelligible to audiences. Compensations of this kind clearly signal that multilingualism of the kind favoured in international projects today is primarily a gesture towards inclusiveness and tolerance. And, like most gestures, it is unfortunately little more than that.

An earlier version of this article was first published in FIRST CITY (May 2006)