Recovering the Republic

Anisha Shekhar Mukherji

1.Plastic Salt Container, in Urban Kitchens 2. Traditional Salt Container 3. Traditional coconut scraper

(Courtesy: Ira Chaudhuri)

I would like to begin with a question. A question asked by an external juror to the first year post-graduate students of Industrial Design in the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture, at the end of their research presentations comparing a traditional craft with its modern counterpart. “Which is more important, the survival of the craft or the survival of the craftsman?”

Considering the abysmal conditions that most traditional crafts-people practice their art in, and the pittance they receive for hours of strenuous creative work, this question is entirely apt. It sums up the entire dilemma in reviving the manifest arts and crafts of India. Traditional craft is today unable to give either dignity or money to support its practitioners in our Republic. To ensure their own survival they abandon it, in favour of the most feasible employment alternative available―as road or building construction labourers, factory workers, domestic help. Such literally back-breaking unskilled work earns them some money. But it gives no surety of tenure, no provision of basic human dignity, no respect for their persons or their labour. We have all seen these labourers in our cities, their children lying unattended in a corner of the dusty road, their habitation consisting of a few plastic sheets. It appears that while soon there may be no traditional artists, having either starved or taken on other jobs marginally better than starvation, the relics of their art will survive as museum pieces in this country and in others, such as the beautiful traditional coconut scraper, from the private collection of Sankho Chaudhuri, Courtesy: Ira Chaudhuri

What then should we do? We who praise and display the skilled products of such hands and minds, in safe and comfortable environments so different from theirs? We do not have to look too far back in space or time for the answer. It was given more than seventy years before, by none other than Mahatma Gandhi. He wrote in 1934,

‘In a nutshell, of the things we use, we should restrict our purchases to the articles which villages manufacture. In other words, we should evoke the artistic talent of the villager’. 1

We have as a country disregarded this advice. The inaction or actions of our own government has resulted in the destruction of traditional habitats and the cultures that such habitats foster. Despite the manifest artistic talent of the villager, our way of life today routinely favours ‘articles produced in big cities, even if they are obviously inferior in workmanship and design. We have segregated things of beauty from things of utility. They reflect our own segregation of lives where we separate work and pleasure into different compartments. Thus our homes and places of work, both from the outside and the inside, use materials that degrade the environment and consume huge amounts of energy in their design, manufacture and maintenance. Most products of daily use in even the homes of the relatively well-off and well-educated are devoid of aesthetic form or detail. What better example to demonstrate this, than to compare the domestic container for salt, the humble but vital ingredient of food that Gandhiji chose to use as his symbol for self-reliance from the British? The photograph above depicts a salt container collected from a rural home, by Sankho Choudhuri in the course of his travels over the length and breadth of the country and beyond. Contrast this with the usual salt container in a kitchen today.

We instill the same lack of feeling for art in our children, in the choices that we make for them. Though traditional hand-made toys, such as the wooden Benaras toy shown below, are practical objects to play with and are beautiful both as examples of craft and of design, it is the mass produced plastic toys of similar price available commercially, which most of us prefer to buy for our children today.

Traditional Banarasi handmade parrot

Plastic mass-produced toy dog

This is a reflection of the ‘colonization of our minds’. We have been conditioned into believing that the only way to progress is to imitate the cultures of the Western countries. This perception continues today, even when it is increasingly evident that the western mechanized model of development is neither congenial to individual creativity, nor sustainable for the earth’s resources. We all know that its factories occupy substantial land, and consume quantities of minerals, water and electricity only in order to mass-produce standardized objects devoid of individual characterization, and made of energy-intensive materials. When they are thrown after use they poison the earth and irremediably harm our habitats. Contrast this with the cycle of production, use and disposal of traditional crafts. Produced in a home environment which does not require any extra investment in separate land or buildings, the natural materials that they overwhelmingly use such as clay, wood, cocoanut shells, reeds, bamboos, do not degrade the environment, but add to its fertility after they are broken or have outlived their use. Thus, the input as well as the output of small-scale craft and design activity is far more humane and superior to the ‘environmental and human cost’ of large-scale mechanization.

Despite this evident fact, and despite a famed artistic tradition that still continues in some measure today, our institutions give credence only to book-knowledge or machine-skills. Most designers and artists graduating from reputed national universities cannot craft anything with their own hands to equal the skill of traditional designers. This is why perhaps they produce banal work that is merely a copy of repackaged and repetitive Western ideas. Those that are in positions to do so, refuse to heed the economic potential of the vast human resource of traditional craftsmakers, which can not only support itself with practically no government investment, but can also earn the country much money through its craft and design skills. Some of our policy documents such as the revised Draft National Design Policy, do state that they would ‘promote value added designs focusing on India’s unique position as a country with a rich cultural heritage…’.2But in real terms many rare crafts-skills, far from being promoted, actually face extinction because they are even refused recognition as an economic industry. Student research shows that possibly the only remaining family in Paharganj in Delhi which practices the craft of hand-woven chiks, have been refused PAN numbers, since only pit-loom woven chiks are recognized by the government as a craft industry!3

Historically, such craftsmen and artists of India have been famed over the world since centuries. So much so, that the eighteenth-century Persian invader Nadir Shah took care to carry hundreds of craftsmen along with all the wealth that he looted from India. The crafts have often reached their pinnacle in cities, and in or around the courts of kings and noblemen. How was it that we earlier managed to develop the potential talents of our people, while we are unable to do so today despite our democracy? In earlier times, as Dharampal, the noted Gandhian historian has recorded ‘…the sciences and technologies…in countries like India…[were] in tune with their more decentralist politics and there was no seeking to make their tools or work places unnecessarily gigantic and grandiose. Smallness and simplicity of construction, as of the iron and steel furnaces or of the drill ploughs, was in fact due to social and political maturity as well as arising from understanding the principles and processes involved’. 4

There was also no active discouragement to village organizations. And an important component of the economy of villages was local talent. The presence of such talent was nurtured, and the best amongst these were given patronage in the cities. Thus in the mid-seventeenth century, the imperial urban palace of the great Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan, in his new capital of Shahjahanabad, had areas reserved within it for artists and craftsmen from the city. These karkhanas, surrounded by gardens and courtyards, had some of the best such artists working within them. Imagine such a situation today. That some of the many rooms within the Rastrapati Bhawan, are given over for master-craftsmen to practice their craft, secure in the knowledge that they are under the patronage of the President! That they will not have to beg or run from pillar to post for raw-materials for their craft, or for buyers for their finished products. It would be a wholly suitable use for the hundreds of empty rooms in the Rashtrapati Bhawan maintained at public cost, but most of us would find it unacceptable, if not downright unthinkable.

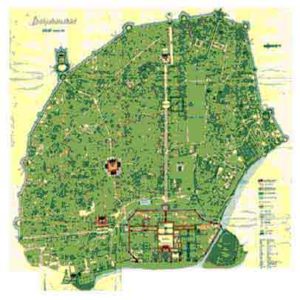

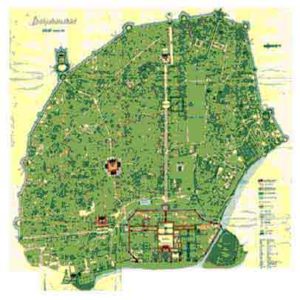

The city of Shahjahanabad, a mid-19th century map of which you can see above, held to be an ideal example of town-planning in its design and functioning, followed the example set by the Emperor. Despite being the capital of one of the largest and richest empires in the medieval world, areas of governance within the city were decentralized. Houses of noblemen and princes were surrounded by that of their dependents, artists and craftsmen. Workplaces and homes were integrated. Ourcities today forcibly separate places of work from residential areas, even in the case of professions which do not pollute the environment in any way. Our law-enforcers separate poorer people into the fringes of the cities. The only end of work appears to be to make money, lots of it; that work can afford creative pleasure is a luxury most of us are afraid to even imagine.

The downfall of a local level of crafts and technology, that in turn fed a corpus at an urban level, began, really speaking with the advent of the European trading companies, three hundred years before Mahatma Gandhi campaigned for the revival of village industries. The sole purpose of these companies was to amass wealth for themselves in the name of fair trade, by deliberately undermining local craft and technical skills ‘by hook or by crook’. The personal and state correspondence between British traders and British rulers and administrators, shows their active connivance to ruin this economic base while at the same time extracting economic and other benefits for themselves from indigenous Indian knowledge. They also show that the fountain head of this knowledge has been the villages. That it still remained in sufficient amount even a hundred odd years after the start of the British operations, shows the spread and tenacity of this knowledge base.5 Thus in the mid-eighteenth century, in the time of the renowned ruler of Jaipur and Amber, Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, the architect and town planner Vidyadhar, despite hailing originally from Bengal―a land many miles east of Amber―could practice his talent with dignity and freedom in Jai Singh’s court. His remarkable design of the city ofJaipur, with its feel for local needs that most of our modern architects and town planners are bereft of, continues to function well till today. The city’s unique identity, unlike its faceless or facile modern counterparts, stems from an integration of local building skills as well as a response to local climate and culture. Vidyadhar could visualize and construct the city in this way because though he came from a culture, whose details and landscape were different from that of Rajasthan, the process of thinking itself was not different. It depended on an elaboration of the local building theme, which was known as much to the local users as to the local builders. The formal basis for this theme was in the Sanskrit texts and building manuals.

For most of us bred to the superiority of city learning, it would be no doubt amazing to realize that we owe the existence of the world-renowned Jantar Mantars as much to a village priest of humble origins as to the famous Maharaja of Jaipur. Jai Singh II met Pandit Jagannath, a Brahmin village priest in the Deccan, whose knowledge of astronomy and religion was so manifest that it catalysed the Maharaja to take the priest back with him to Amber. This also demonstrates that learning was not limited to cities or courts. Pandit Jagannath went on to become Jai Singh’s chief aide in his astronomy researches and in the theory and practical construction of his unique masonry instruments of astronomy. It should also give us some food for thought that this is described as one of the darkest periods of Indian history, by many Western historians.

In what seems to be a perverse joke of history, the very nation that once led the race to wipe out indigenous Indian methods of living and crafts production, has now adopted a direction of economic growth that depends to a large extent on crafts and creative industries. The merely 32,000 crafts makers of Britain surpass the earnings of its organized industries of motorcycle or sports good manufactures.6 Ironically, despite our estimated population of ‘over a crore of handloom weavers, and an equal, if not larger, number of crafts people engaged in diverse crafts from pottery, to basket-making, stone-ware, glass-ware, hand made paper products and multifarious other utility items made out of local, available materials’,7 our policy makers assiduously continue to court a centralized large-scale, high-investment, and polluting model of western development.

The fact that there is a global market for Indian crafts is quite evident from the quantities that are bought by visiting foreign tourists, and by the fact that China is now mass-producing objects in factories that imitate Indian crafts, to tap into this demand. However, the export of crafts does not always imply the preservation of the artists. Thus, despite earning huge amounts of foreign exchange, the woodcraft of Saharanpur no longer succors the traditional craftsmen. Even local demand is by itself not enough. Despite a continuing demand for gold jewellery, traditional goldsmiths in Tamil Nadu from the Vishwakarma community, are starving. Customers now go to showrooms owned by jewel magnates which stock machine-made jewelry instead of the custom-made designs of traditional goldsmiths. One imported jewel-making machine does a year’s work of ahundred goldsmiths in about ten hours. From the late 1990s, this increasing mechanization in jewelry-making has led to the suicide of several goldsmiths, many with their entire families, by consuming cyanide, which every goldsmith uses to polish gold. Most of the remaining two lakh goldsmiths in the state, are in debt. About two thousand of them are now reduced to selling liquor in government run shops.8

Not content with wiping out indigenous craft and technology by patronizing large scale industrial investments, even the land of rural communities is being taken away. The recent Bill devised by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Rural Development, appears to be even more exploitative than the archaic Land Acquisition Act of 1894 that it seeks to replace. The new Bill according to Medha Patkar, the veteran activist who leads the National Alliance for People’s Movements, (NAPM), removes the more public-spirited provisions in the colonial government’s Act. It instead, includes a clause that may be invoked to assist private companies in acquiring public land for ‘any project relating to the generation, transmission and supply of electricity’ and even ‘mining activities’.9

This is why, despite protests by village groups, Gautam Adani, ranked 91 on the Forbes’ World Billionares list, has been able to buy land at rates between Rs 1 and Rs 8 per square metre10, 11 from the Gujarat government for the SEZ coming up on the northern shore of the Gulf of Kutch in and around the Mundra port. This land, including government revenue and forest land, and more than 1400 acres of gauchar or grazing land under panchayats, has been leased to other companies by the Adani Group at Rs 1000 per square meter.12 The Adani group, the new ‘company bahadur’ has killed fragile ecosystems including more than a crore of mangrove trees, appropriated common property resources, and displaced ‘local people who since centuries earned their livelihoods based on access to the land and the sea’. 570 hectares of mangrove forests have been cleared through industrial activity, the fish-species they spawned have been destroyed, the local Wagher fishing community’s and the traditional cattle/buffalo rearing Rabaricommunity’s livelihood has been permanently lost. Country-craft builders at the Old Mundra port which generates an annual income of a crore to the Maritime Board are also at risk. The smooth roads and infrastructure that the SEZ boasts as justification for all this destruction and displacement, are a stark contrast to the kuchha roads outside its boundaries without basic water and sanitation where its more than 10,000 migrant labourers are made to live. Despite such obvious exploitation, our obsession with foreign investments and stock markets have made us as a country blind to such usurpation of the lives and rights of village communities.13

How then, to return to the original question, do we ensure the survival of crafts people and their art, against the new colonists?

First, we must understand that it is only in the village, that these craftspeople can survive with dignity, in a familiar environment that promises them the security of some level of relationship with their land and with its society. Second, we need to ensure that their craft brings them and their families enough to live in the villages, without fear of starvation or eviction. Third, we must place the invaluable knowledge embodied in craftsmen, on an equal footing with that of the degreed faculty who teach in our institutions at enviable salaries.

To do all of these, craft has to come out of the ambit of merely ‘decorative objects’ After all, how many carved elephants or statues can one display in ones homes? They must regain their status as objects of utility that are also beautiful. If all objects of daily use are designed and crafted using the manifest skills of our traditional artists–plates, glasses, spoons, knives, lamp-holders, furniture pieces, photo frames, hair-grips, there will be a real demand for such objects and they will be part of a living tradition of use. This in turn, will ensure that there is a continuous demand for such objects, which will afford craftspeople sustained employment in producing them. As Sankho Chaudhuri has said, ‘The time has come to ask ourselves what we want to [do] with the potential talent of the artisans. We have to consider whether the village and tribal crafts should be used only as a means of earning foreign exchange and keeping alive otherwise meaningless, moribund forms and crafts (like gold sequins and brocade work on velvet or rose water jars) or whether we could apply their skills to evolve designs of utility, and develop simple cheap objects of daily use which every villager can afford, like clay toys, deities, oil lamps and so on, and try to create an economic base for these artisans to survive in the villages.’

It so happens that most of us are now used to certain conveniences, and if crafts objects are to replace mass-produced objects of daily use, they must have a certain convenience of use and ease of maintenance. Their appearance and detailing also needs to be in tune with more contemporary aesthetic sensibilities. Craftspeople additionally need help with access to raw-materials as well as packaging and marketing-skills. Therefore, we must decentralize the practice of craft and technology as well as the decisions that govern them; and foster interaction between those taught in the present design and technology schools and those trained in traditional arts and technologies, so that there is mutual transmission of learning. This is not in the realm of the impossible. It can be done. The collaboration between traditional Bidri artists whose fine metalware craft with inlays of silver, brass or copper is now almost exclusively centred in Bidar near Hyderabad, and Vikram Sardesai-a Bangalore based designer- has produced new designs which are distinctive, beautiful and useful, like Serving Plates designed with new motifs, manufactured and embellished according to the traditional techniques of Bidri ware &Keychains manufactured and embellished according to traditional techniques ofBidriware.11

The range, quality and packaging of these products has, as Vikram Sardesai says, made the corporate world look ‘…at indigenous solutions, rather than constantly buying from the West and China…’15. However, well-detailed crafts-objects suitable for daily needs of modern living, need to be stocked at neighbourhood shops within the ambit ofordinary consumers as well. For this, we have to generate a local demand for such products, within our own cities, towns and villages, so that there is a steady market that does not depend on huge production numbers. This will foster the necessity for local artistic talent. From this talent, those who do come to cities in the lure of fame and wealth, will like their historical counterparts be among the best practitioners, ensuring that they are not led to do downgraded jobs as today, but instead are elevated to positions of respect. And since most villagers and small-town dwellers aspire to be like the city-dwellers, this demand for village-crafts must come from city-dwellers. It is surely a small thing to ask, that we use objects that fill our daily life with beauty, which additionally help to keep alive in dignity those of us who have the talent to create such objects?

As Mahatma Gandhi said so many years ago:

‘Each person can examine all the articles of food, clothing and other things that he uses from day to day and replace foreign makes or city makes, by those produced by the villagers in their homes or fields with the simple inexpensive tools they can easily handle and mend. This replacement will be itself an education of great value and a solid beginning.’ 14

Everyone present in this conference, can resolve to move beyond discussions, to use as much as possible articles produced by indigenous crafts-people in our offices, and in our homes. We need to convince as many people as we interact with daily, our families, our friends to do the same. Whichever of us are teaching in institutions, must initiate the inclusion of traditional knowledge-bearers on the staff- as visiting lecturers, as faculty, as part of special training measures. Those of us in the government can set an example to use indigenous alternatives for office décor and office stationary, such as bamboo chiks instead of plastic blinds. We also need to facilitate the making and transformation of the houses which often double as workplaces for craftspeople, into well-lit, ventilated and healthy spaces, whether through trained advice or through the promulgation of rules which legalize such multi-use dwellings. At a policy level, the Government of India needs to ban the setting up of large mechanized efforts that compete with indigenous craft and technology, and enforce laws that forbid large-scale machine production of traditional skills such as of gold-jewelry and instead propagate and practice decentralized methods of production.

. Only then can we recover the basic tenets on which our Republic was founded. Otherwise, our very existence will be a mindless copy, like the idols we worship―now being produced by machines in factories in China. I would like to end with one such Chinese machine-made idol, displaying facial features reminiscent of the land that it was manufactured in, with the hope that true to the spirit of our tradition, our gods and goddesses shall prove an auspicious omen for the revival of Indian arts and crafts and their practitioners.

References

- Harijan, 30-11-1934, M.K. Gandhi, (As printed in Village Industries, Navajivan Publishing House, 1960)

- National Design Draft Policy 2007

- Unpublished Research Paper, 2nd semester, Industrial Design, School of Planningand Architecture, New Delhi, volume 1, pp. 43-4, Keerti Dixit

- Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century, Some Contemporary Accounts, Introduction, p. 31, Other India Press, Goa and SIDH, Uttaranchal 2007.

- Ibid. Introduction, pp. 1-35.

- Jaya Jaitly in Seminar, September 2005, Creative Industries, p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 15.

- Tehelka (17 May 2008), pp. 18-19

- Civil Society; April 2008, Civil Society News,

- Seminar February 2008, Issue on Special Economic Zones, p. 42. ‘land at the price of water’, as Irshad Bukhari, sarpanch of Mundra grampanchayat says.

- Down to Earth, p, 30, May 16-31, 2008.

- Seminar February 2008, Issue on Special Economic Zones, p. 42

- Manshi Asher and Patrick Oskarsson, Ibid., pp. 40-43

- Harijan, 25-1-1935, p. 13, M.K. Gandhi, (As printed in Village Industries, Navajivan Publishing House, 1960)

- Indian Design and Interiors, p. 42, Vikram Sardesai

- ibid., p. 43