Presence Perfect (Keval Arora)

Keval Arora’s Kolumn

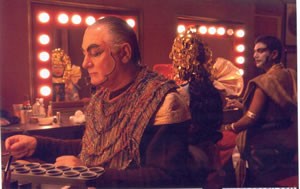

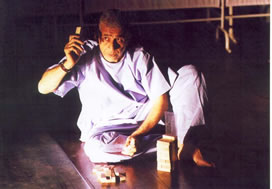

- Barry john as Iago in ‘Othello’ 2. Naseeruddin Shah in ‘Prophet’

Presence Perfect

Mulling over oddities that years of familiarity have lulled us into accepting as normal, one curious habit that comes to mind is the way we respond – or, to be specific, don’t respond – to the physical presence of the actor in our estimation of plays and performances. It is strange that this dimension of playmaking rarely crops up in reviews and analyses. Even if it does, the enormous contribution that the actor’s physical presence makes to his role or to the play’s meaning is often insufficiently acknowledged. We tend instead to focus on such qualities as are amenable to correction, training and control. (This is understandable. If skill is to be celebrated, surely skills for which we can claim authorship will come higher in our estimation than will those over which we have little control.)

Yet, our immediate experience and our lasting memories of the performances we see are mediated by and interwoven with the actor’s physical presence — the actor in the flesh, so to speak. Think of Barry John’s fleshy middle (he even punned on the Shakespearean word “pate” with the Hindi word for stomach) in Roysten Abel’s Othello: A Play in Black and White, and you realise a leaner actor just couldn’t have intimated that whiff of seedy corruption which Barry’s Iago did. Or, remember the classic reviewer’s comment about how a pimply actor in the role of Hamlet completely alters our understanding of the line that something is rotten in the state of Denmark.

Jokes apart, this last comment is suspect because it suggests the argument that the core meaning of plays needs to be freed from the tactless exigencies of their performance. To my mind, this is not simply a defensive position but also an odd one, for it leads directly to a contradiction in the practice of theatre criticism.

Theatre scores over cinema through the simple fact of corporeal presence. Its qualities of face-to-face contact and physical proximity give theatre a visceral power that the technologically disembodied cinematic image can never possess. (Does that explain the pressure on the cinema to push towards greater and greater realism?) Naseeruddin Shah often speaks of the high that actors experience when performing in front of a live audience. Audiences experience an equal if not a greater high when watching Naseeruddin Shah live on stage. This compact of physical immediacy is the true strength of the theatre. Deny it, and you dilute the medium.

How then can we speak of the physical presence of the actor as a threat to the production of meaning? Worse, how can we not speak of it at all? Theatre criticism and play reviews in Delhi tend to tread a safe path by ignoring physical and stage presence altogether. Reviewers go into all kinds of intricate details, but commenting on the physical attributes of the performers, even when it is germane to the play-text, is apparently a “no-no”, and akin to an invasion of privacy. But, can one avoid commenting on the physical, in a performance art that is of the flesh? The actor’s medium is his body. No analysis of a product can ever be complete if the critic fights shy of talking about its tools.

Take Yatrik’s Harvest. Ginni, an American who contracts the body of a poverty-stricken Third World “donor”, is described in the stage directions by playwright Manjula Padmanabhan as “the blonde and white-skinned epitome of an American-style youth goddess. Her voice is sweet and sexy”. The actress cast in the role, Monsoon Bissel, did a competent job of emoting her role. But even with only a close-up to go by (we see only her face on television monitors), it was apparent to all that the director had taken liberties with the playwright’s vision of a cellophane-packaged desirability.

Surprisingly, not a peep about this was heard from the critics who otherwise tore up the production. Probably because any comment on the actress’s appearance would inevitably imply, no matter however politely hedged, that she isn’t the type to fuel a fantasy ride. Such comments, though valid as a response to the production, could appear as a personal and therefore an unwarranted attack on an individual. The fear of appearing tasteless makes cowards of us all.

Considerations of taste and tact prevent issues from being tackled head-on, even when facts stare you in the face and remaining silent becomes a sign of professional ineptitude. No one, to the best of my knowledge, has yet pointed out that much of the popularity of the English-language ‘Musical’ theatre rests upon its flagrant display of nubile bodies dancing in gay abandon. That this is an unstated premise of the musical was unwittingly revealed by Delhi Music Theatre when it advertised its Fiddler on the Roofby plastering Bengali Market with posters which read in effect that 5 broad-minded girls were on the look-out for men!

Such blurring of the critical gaze becomes evident in those cases where comments on physical presence would in fact be appropriate. For instance, in the English language comedy that came to be known as the Sex Comedy in the shorthand of the print media. In a script where the male roles are envisaged as dogs on a leash, the female leash, sorry lead, usually went to an actress in whom acting talent was a bonus but the requirement of “oomph” was non-negotiable. The reviews, however, treated these productions like any other. When talking about body parts would have been far more attuned to the aesthetics of the show(ing), their focus on acting skills seemed perversely cruel to the audience, the director and the ‘act’ress. Especially as (like in Harvest) the gap between intention and fact was often embarrassingly acute.

What is ironical about such silence is the fact that everybody on the other side of the curtain trades extensively on the physical in shaping textual meaning and audience response. After all, playwrights, directors and performers don’t go through casting auditions with their eyes closed. But, when it comes to concluding the pact from this side of the curtain, the protocols of viewing shift from the aesthetic to the social. Decency and propriety suddenly stake a claim as aesthetic criteria. Comments on physical presence are derided as “nasty” reviewing, and banished to gossip boudoirs. What better proof does one need of Delhi’s theatre community being a large club (of course there’s much heartburn amongst its members, but which club is free of squabbling?) than the fact that even its reviewers observe the social protocols?

I can understand analyses being circumspect if the actor’s physical attributes are, as seen from a mainstream perspective, socially disadvantaged. Saying that an actor has too thin a voice to play the swaggering bully is a ‘no-no’. But laudatory descriptions bring other problems. For example, there’s no denying the fizz in Rahul Bose’s stage presence. But, in Seascapes with Sharks and Dancer, this strength militated against his role as a reclusive writer. Bose thus seemed to play a man who was quiet by choice rather than situation, cool rather than conservative, and sexy rather than scared stiff. Much praise was heaped on Bose as if stage presence is a talent in its own right, regardless of the way it mangles the script.

The real complications in critical response occur when a production does not fit neatly into the black and white categories of convention. When normative perceptions of the physical are inverted, when what is conventionally regarded as ‘inferior’ is celebrated and the ‘superior’ is destabilised, the degree of difficulty gets too much for polite reviewers to handle.

Maya Rao, for instance, wouldn’t win anybody’s vote at a beauty contest (I say this with all the presumption of a friend), and it is this absence of the ‘media’ted sense of the feminine that imparts a hypnotic quality to her stage presence. Whether it is Maya cupping her belly and speaking of the distinctive female muscles of the underbelly and the thigh in the course of her stage performance of Bertolt Brecht’s short story The Job, or Ritu Talwar similarly challenging cultural codes of the feminine by physically emphasising the masculine aspect of her presence (in Anuradha Kapur’s production of the same Brecht short story), the principle is the same. Both refuse to conform to picture-frame ideals of the feminine as endlessly replicated by the media and internalised by a whole generation of anorexic feel-gooders, (This feminine icon is seen best in our younger film heroines. They are such clones – physically, mentally: who can tell – of each other that like quality assembly line products, it is difficult to tell them apart.) Maya and Ritu’s refusal to conform marks the primary source of these actresses’ challenging, transgressive power.

How can any discussion of such performances be complete if the critical discourse makes no accommodation for the body as a site of meaning? Obviously, the body is not just fair but necessary game in the business of reviewing. If sociality and its norms are allowed to thus infect the critical will, reviews may end up displaying the very symptoms that such productions seek to challenge.

Not that this solves the problem, for there is another side to the tale. Steven Berkoff explains why actors will forever be sensitive to criticism that accommodates discussions of the body: “The actor’s working material is his own body. With painters, sculptors, etc, your work is separate and distinct from you. Criticism is therefore far more personally wounding to the actor that it is for other kinds of artists.” In fact, in talking so carelessly of the actor’s physical presence, I too may have presumed upon the insurance of friendship. It’s another matter that Maya may cancel the insurance. Or, she may insist as a well-known director had declared at a workshop, that there can never ever be friendship between performer and critic.

Which simply begs the question: Why in that case should protocols of the public and the personal be so religiously observed? The actor’s medium is the body. The critic must factor that into the analysis. Amen.